By

Gulcin Newby Kennett

In the chapter called ‘Films of Memory’ from his book ‘Transcultural Cinema‘, David MacDougall explores the intricate relationships between human memory and films.

He begins by stating that memory, as it plays itself in the human mind, is a product of the complicated processes of senses (especially visual) and brain. Since memory occurs entirely within the mind, the biggest challenge for filmmakers was to represent the complex topography of what takes place inside the mind. After acknowledging the strange and incoherent blend of sensory and verbal elements that constitute memory, we find its closest counterpart in the realm of film, MacDougall introduces a concept, which he calls; ‘the mind’s eye’.

According to MacDougall, while attempting to represent memory, the filmmakers instead “create signs for things seen only in the mind’s eye.” He argues that the intensely visual nature of cinema inevitably helps simply create more images that only refer to the actual objects or events. And incidentally, these same images help us recreate memories of the past, by becoming solid visual imprints in our mind’s eye. At this point MacDougall’s argument becomes quite Platonic (i.e. Plato’s well-known Allegory of the Cave) when he points out that after the introduction of photography (and film subsequently), humans began to think not just visually, but also photographically. Most of the recent historic events are remembered by many not because they were actually there, witnessing the event, but because they have seen a photographic capture (footage) of it, (i.e. remembering the JFK assassination not because one was actually there in Dallas that day, but after having seen the famous Zapruder film footage – a 26 second silent color motion picture sequence shot by private citizen Abraham Zapruder with a home-movie camera).

MacDougall mentions four distinctive signs of memory in his ‘films of memory’, the first of these a sign of survival. This is when a filmmaker is trying to refer to a memory he/she uses objects (or people and places) which have a direct physical link to the remembered past. We can see a unique utilization of these signs in Alain Resnais’ 1955 film Nuit et Brouillard (Night and Fog).

In this film the director presents us with a collage of black and white Auschwitz photographs made by the Nazis, and a color film of the ruins of the concentration camps that was shot ten years after the war. In the case of this particular film the photographs become the visual testimony to the events, which took place in the past, while the color footage represents the present time.

The ‘Sign of replacement’ is widely used when filmmakers decide to recreate the past when there is no actual physical link (or footage) available. This is a common practice in some of the popular expository crime (or scandal) documentaries on television.

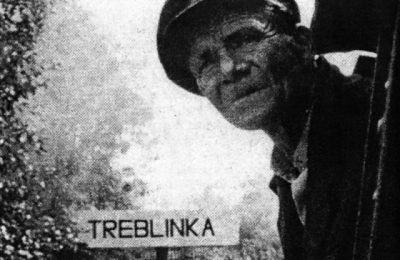

The first three types of signs, which are found in most conventional films about the past, actually form a single larger class. MacDougall claims that these types of signs only help create a false sensation that the past can actually be recreated as in memory (or as if we could bypass memory). In his opinion, only a few remarkable films make use of a different class of sign, namely the signs of absence. These signs take into consideration the tricks that memory play on us humans, especially if the actual events took place in some distant past. In a dialectical sense the actual object (or anything connected to it) is defined by its absence in film. A very typical example of a film that heavily relies on the signs of absence is Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour documentary called ‘Shoah’ – it is the term in Hebrew to refer to the Holocaust.

In this film not a single frame or archival material is used, and the lengthy interviews with the ageing witnesses to the Holocaust are sliced into small episodes in a very complex narrative, which is built on circles and recurrences. In this way, the viewer is not forced (or spoonfed) a version of the past that is based on solid evidence, but instead is left alone to draw his or her conclusion. This is what makes Lanzmann’s film not only an experiment in avant-garde, but also a strong statement on memory.

This is an exquisite article for intellectuals, film makers and film lovers.