By

Anant Mishra

Introduction

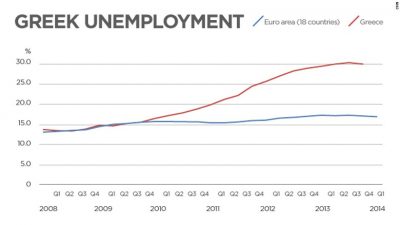

Greece is caught up in a major financial crisis leaving the financial experts bewildered on the Gre-exit. Now, in its sixth year of crisis economists are focussing on Greece. More importantly, since the beginning Greece failed to maintain a stable deficit as it continued to repay the financial debt, deepening their financial crisis. Today Greece continues to face exponentially high unemployment rates, while the Greek banks run out of money.

Following unsuccessful negotiations between the Greek government and creditors, the current debt has grown aggressively.

After receiving a default on a major IMF payment followed by a unanimous “no” vote on the Greek Bailout Referendum in July 2015, with respect to the recent Bre-exit, economists believe Greece will bid adieu to the EU. If Greece fails to strike another deal with the EU leaders, it will be forced to exit the EU. While many financial pundits state “no effect” on the Eurozone, others state the downfall for the EU along with a steep decline in the European markets, which will further push the dollar as the pound will face one of the major depressions. With no concrete discussions between the political leaders and no policy at play, the future of the Euro remains unpredictable.

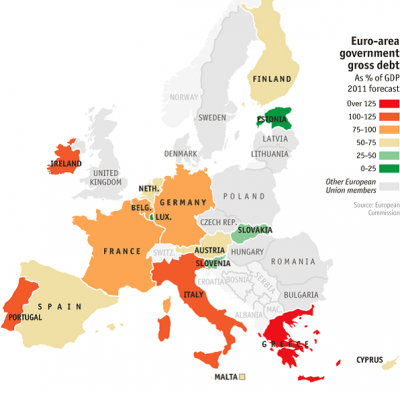

Moreover, it is important to note that the Greek debt crisis does not affect the people of Greece, but has left major implications on power nations such as France and Germany. As major creditors to Greece, France and Germany are hanging between the balance of writing more cheques and a complete withdrawal from aid. Although citizens of France and Germany have called for an immediate exit, the fact that ‘Grexit’ will leave no consequences behind cannot be completely ruled out. One of the major concerns here is a “chain-reaction”. If Greece leaves the EU, nations such as Ireland or Portugal may find themselves in a similar situation. These countries have been receiving extensive bail out packages, and are highly likely to “get sunk in crisis”. Beside Europe, the Greek debt crisis has affected the global economy. Despite its small participation in the EU and in the global economy, stock markets have been heavily fluctuating because of the volatility created by the Greece debt. There will be serious consequences for the global economy if Greece exits the EU.

There have been a series of conferences, summits and discussions between head states to discuss the issue of the Greek debt, which failed to provide any solid resolution. With almost no solution in hand, member nations need to sit more frequently to discuss the future of Greece, as it will then be forced to find resolutions on its own.

The beginning

The Greece debt crisis has its roots from the volatile markets during the Cold War, triggering economic ripples right after its entry into the EU. As soon as Greece became a part of it, financial organizations began offering lucrative assistance programs or loans to the Greeks. It is also important to note here, that most loan seekers were in no condition to repay the loans. In order to reduce the then growing debt, the government then cut finances on all public services, except the military, thus creating a threshold between the public and private entities, forcing private investment to drop. The heavily decreased job opportunities later resulted in an exponential increase in unemployment.

More notably, in the 1980s, Greece was not just facing economic challenges, there were some major political issues too. Up to the 1974 referendum Greece was still under a dictatorship government. The year 1980 saw massive state spending as the nation opened its doors to democracy. Although spending enormously on the new democratic system, it played no positive role reducing the debt to the crisis we see today.

In 2001, Greece entered the Eurozone. While addressing the media, the then President of the European Central Bank (ECB) “warned that Greece had much to do in terms of improving its economy and controlling inflation”. There were certain policies that nations in the Eurozone disagreed on, one such was a rule which stated that “a country cannot have a budget deficit of over 3% GDP”. Most Eurozone nations went against this, but Greece went too far, hiding the current account deficit from other nations for over two years until the 2004 Athens Olympic Games. As nations began balancing the budget, the country’s global tax collection collapsed in 2008. By mid-2009, the nation’s deficits reached an alarming 12.5% of its GDP. By 2009, Greece’s financial debt could not be ignored. From October until mid-December, the credit rating of Greece hit rock bottom, making it increasingly difficult to borrow money. With no viable solution left, the ECB and the IMF began creating bail out packages for Greece. Between 2011 and mid 2013 Greece’s financial debt increased despite the government’s desperate attempt to stabilise the economy. Despite violent protests from the Greeks, seven austerity packages were passed. Public services were drastically reduced, government expenditure decreased, wages lowered and taxes were increased to 23% in an effort to receive the two bail out packages from the ECB, European Commission, and the IMF. Irrespective of these efforts, the bailout program failed to improve Greece’s economy. This sent the Greek economy into a depression.

The situation today

In the general elections of 2015, the anti-austerity Syriza party won by a huge majority, and were now new policy makers of the nation; Alexis Tsipras becoming the new Greek Prime Minister. Immediately after the elections, the new government then asked the IMF to hold the decision of €1.6 billion bailout grant till the end of the month; as the deadline grew near, policy makers and economists knew the situation was out of control. Three days before the deadline, Tsipras then announced a new public referendum asking citizens whether to accept the harsh conditions in return of the bailout package. Tsipras then led the ‘no’ campaign, calling the decisions “humiliating” for Greece.

As the deadline approached, the Greek banks began to run out of money. As a direct result of the economic crisis, all the banks were closed. Realising the harsh economic conditions and tensions among the Greeks, the government then decided a withdrawal limit of €60. In the same month, Greece fell into arrears with the IMF. This was the first time ever a developed country had been marked as a default for an IMF loan since its establishment in 1945. This default extensively damaged Greece’s credits, and placed a huge risk of Greek markets pulling out of ECB’s Emergency Liquidity Assistance. Moreover, as the bailout referendum neared, the possibility of a “no” vote increased amid media speculation. As a matter of fact, over 61% of the people rejected the bailout conditions, bringing the fear of all, for the end of Greece in the EU. The newly elected government may have supported the ‘no’ vote, but this referendum put Greece in a very difficult position with only one relative outcome, exit from the EU. Voters made it very clear that, no more austerity crises will be accepted, but the government still remains desperate for money. The Greece government, on its own consensus sent letters to the creditors seeking a third bailout package to prevent ‘Grexit’.

The letters written to the creditors were initially rejected by the Greeks. Many power nations had a different perspective: nations such as Italy and France were quite optimistic, Germany the largest creditor for Greece, remained sceptical about Greece’s future.

After a series of discussions, a third bail out of €86bn was agreed, to be granted over the next three years. The agreement is hard on Greece’s economy and austerity, which is not a viable solution for the country’s economic growth. The ruling party saw Tsipras’ deal and a betrayal against the party’s anti-austerity principles and rebelled against the Prime Minister. Even as the rescue package fuelled Greece’s participation in the Eurozone for a few years, over 149 Syrizan MPs revolted and rebelled against the Prime Minister, asking for his immediate resignation. On August 20th, Tsipras resigned, leaving the country’s future in the hands of Vassiliki Thanou, Greece’s top Supreme Court judge. Since the third bailout package, markets have been responding quite negatively, experts suggesting that the elections in Greece will not affect the economic situation.

As Greece’s debt continues to increase, the nation, on its own has been trying to stabilise its economy. Even if Greece is able to do so, it will still need 42 years for the country to be debt free.

Possible Solution

What happens if Greece accepts the harsh austerity conditions and agrees with the rest of the EU to draft a new reform policy? Many experts have agreed that Greece, after struggling on two fronts (economic crisis and refugee crisis), will not be able to make critical decisions on its own.

Nonetheless, if the Greek voters are against the idea of austerity measures, the need to receive necessary funds will outweigh the will of the voters. If Greece and its creditors come to an agreement, the nation will be able to receive the necessary bailout and stabilize the economy, in a much shorter time. Banks will then be operational again, and the Greek people will be able to withdraw more than €60 per day. Here, Greece will remain a part of Eurozone. Since austerity packages have not been successful in Greece’s case, this solution is viable to avoid a Grexit: leaving a weaker Greece and a weaker Eurozone. Many Eurozone nations have different solutions. Many power nations such as Italy, France and Germany focus their agenda on a European Integration, German citizens losing their patience in the process, as their money is used to bail out Greece. It is also not viable because austerity packages have not yet proven to be successful for Greece. This solution will bring the nation into the same situation as it was in 2009.

What happens if Greece rejects all solutions and exits from Eurozone?

‘Grexit’ will become the only viable solution if negotiations between Greece and the ECB, the IMF and the EC fails. Many EC financial experts have already stated that Grexit will cause a minor financial ripple in the first four years, but will benefit the Eurozone and Greece in the longer run. With a weak currency Greece will “inflate away a chunk of its debts and become much more competitive”. As a result, Greek exports will become cheaper, irrespective of the fact that Greece is not a major exporter.

Most importantly, the benefit lies with the Eurozone. Moreover, most economists still stand to the point that Greek’s economy will be devastated if it tends to leave the Eurozone, which is currently supported by the ECB. A weaker currency will lead to high inflation, putting excessive economic constraints on the Greeks.

Following Bre-exit, the majority of countries do not wish to witness ‘Grexit’, Germany, on the other hand pointing out the importance of Grexit as “fruitful” for both.

Anant Mishra

Anant Mishra is a security analyst with expertise in counter-insurgency and counter-terror operations.

The circumstances surrounding a possible Grexit are a bit different to the Brexit. Greece has to submit its budget for approval to the World Bank and IMF, reflecting its subordinate position vis-a-vis the powerful EU institutions. London still has enough financial clout to deft the EU and demand concessions from the latter, even though Britain is a formal member. The Brexit, while distorted by the ultra-right into an anti-immigrant outburst, is actually also a step forward for the working class. The demand to Leave the EU was a traditional Labour-Left position, articulated by the late great Tony Benn back in the mid-1970s, when Britain was first contemplating membership of the EEC, the forerunner to the EU. Benn realised that the EU was evolving into a financial dictatorship, a bankers institution that would implement policies that allowed freedom for capital to cross borders, but not people. Having said that, successive British governments have implemented austerity and cutbacks to jobs and living conditions without any help from the EU. Thatcher lead the ruling-class charge to close mines, shatter mining communities, break up the unions, and reverse many of the social gains of the post-WWII British welfare state. The ultra-right anti-immigrant parties have jumped onto the anti-globalisation bandwagon since the 1990s, diverting attention away from the corporate structures of power, and directed legitimate working class anger towards other vulnerable communities, such as migrants and refugees. The campaigners for Brexit - such as UKIP - definitely mobilised bigotry and racism for electoral success in the Brexit referendum. But this is not the first time that this has happened - successive Tory and Labour governments have pandered to anti-immigrant sentiments among the electorate for electoral success. It was Cameron himself, the Remain poseur, who stated back in 2015 that hordes of marauding African migrants and refugees threaten to swamp Britain and its culture. If that is not inciting anti-immigrant prejudice for electoral reward, then I do not know what is. I think any exit from the European Union must be done on a collective basis, that is, several countries should combine to reject the EU bankers framework and establish an alternative social Europe. Just a few observations.