By

Cynthia M. Lardner

Wars and hasty post-war dumping through 1972 left oceans, rivers and lakes around the world littered with hundreds of thousands of tons of bombs, mines, torpedoes, grenades, depth charges, and ahead-thrown submarine weapons, conventional weapons referred to as Explosive Ordnance (EO) or unexploded ordnance (UXO), chemical weapons, and munitions debris.

“Around the world thousands of tons of munitions lie rusting on the ocean floor. They consist of both explosives and chemical weapons. As the metal rusts away, the toxic chemicals are exposed causing an environmental wasteland around them,” stated Terrance P. Long, who was involved with Chemical Weapons Search and Assessment (CHEMSEA), a six year project in the Baltic Sea, and Chair of the International Dialogue on Underwater Munitions, an NGO.

While research is ongoing, it appears that the existing and potential risks to the environment and to human health are contingent not only upon whether it is a conventional or chemical weapon or munitions debris but, also on degree of degradation, the location and whether there is direct contact.

Conventional Weapons

The impact of degraded conventional weapons on the nearby marine environment has been established but the extent of the damage is still being actively researched.

One example of ongoing research is in the waters around the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, which was used as the U.S. Navy’s primary Atlantic training site for a 60-year period ending in 2003, during which time thousands of bombs were left in the waters and where the USS Killen was scuttled in 1975. After being decommissioned, the USS Killen was used as a nuclear weapons target during tests conducted in 1958. In 2005, the Environmental Protection Agency declared Vieques to be a Superfund site. In the years immediately after 2003, the U.S. Navy expended an estimated $350 million dollars on cleanup efforts.

A 2009 investigation was initiated by the Puerto Rican governor amid concerns that 200 barrels of unknown origin and content near the site of the USS Killen were emitting radioactive material. Dr. James Porter found no evidence of radioactivity.

James Porter measures a 2,000-pound Navy bomb in the waters off the Puerto Rican island of Vieques.

What Dr. Porter did find is that the marine life, including reef-building corals, feather duster worms and sea urchins, closest to bomb and bomb fragments in the waters off of Vieques had high levels of toxicity. Carcinogenic materials were found in concentrations up to 100,000 times over established safe limits.

Residents on the island of Vieques were found to have a 23% higher cancer rate than Puerto Rican mainlanders. The fear was that low level carcinogens had worked their way up the food chain. Dr. Porter was unable to substantiate that claim.

“We have not yet traced these contaminants from the reef to the dinner table, but we definitely know these contaminants are in the marine ecosystem,” concluded Dr. Porter.

“Underwater ordnance corrodes and leaches out known toxins and carcinogens. In the ocean, we have measured these toxins in the water, in the sediments, and in living plants and animals near UXO. In one survey in Puerto Rico, every organism near unexploded ordnance had carcinogenic concentration of explosives and high-explosive degradation products. Organisms in physical contact with the underwater bombs often showed signs of disease,” stated Dr. Porter.

Overall, large fish have the highest levels of contamination. But, even small fish used for human consumption, like sardines, have been found to contain high amounts of concentrated toxins.

“People who eat fish or shellfish from contaminated areas are at risk. We know that detectable amounts of UXO-derived carcinogens are present in fish located in some local fishing grounds. The presence of these carcinogens in seafood is of great concern in coastal areas with sea-dumped munition sites off-shore. Although this pathway, from ocean to table, has not been investigated carefully, it needs to be.”

“From my perspective as a marine ecologist, one of the most worrisome aspects of this topic is how little we know about the effect of unrecovered ordnance on sea-life. We cannot assume that what we know about the toxic effect of munition constituents on people automatically allows us to understand what they do to sea creatures. Environmental health and human health are not always the same thing. To maintain a healthy and productive ocean, we need information on the effects of these chemicals on marine life. We don’t have this information. As the magnitude and geographic scope of this problem becomes clearer… it now seems that there are very few coast lines, rivers, or lakes that do not have some level of UXO pollution… the urgency and importance of finding out what UXO does to aquatic life increases as well,” stated Dr. Porter.

Since the mid-2000s, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has been cleaning-up UXO and researching UXO’s impact on freshwater, estuarine, and marine environments. For instance, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers identified more than 400 formerly used defense sites containing underwater and beach UXO spanning from Maryland to Hawaii. Remediation is well underway. For instance, in 2016, the Army Corps of Engineers began an $8.1 million project to clear 234 acres in the Little Neck area at Cape Poge Wildlife Refuge of UXO that have littered the beach and Cape Poge Bay. At that site, Explosive Ordnance Disposal specialists have dealt with 291 UXO, including three-pound practice bombs, 100-pound practice bombs, and flares, and 1,453 pieces of debris. Little Neck is the first of several remediation projects on Martha’s Vineyard; with another $9.8 million dollars pledged.

Chemical Weapons

Governments around the world also dumped chemical weapons into our waterways. The April 27, 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention, ratified by 192 nations, is administered by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). The OPCW’s mission is to eliminate chemical weapon stockpiles, ensure the nonproliferation of chemical weapons, and to provide assistance and protection from a chemical weapons attack. The Convention does not address the environmental risks from chemical weapons.

Twenty-five years earlier, the U.S. Congress passed the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972, referred to as the Ocean Dumping Act, prohibiting the dumping of wastes, including chemical weapons, into U.S. territorial waters, extending outward 24 nautical miles.

However, by then, 40 thousand tons of six chemical weapons, including nerve and Sulfur mustard agents, found in both shells and canisters, had already been dumped in U.S. territorial waters. This includes at least 26 chemical weapons dump sites off the east and west coasts, some of which are unknown due to World War I records having been destroyed before any problem was identified and due to migration based on water currents.

The U.S. Army is cleaning up chemical weapon sites as they are discovered. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides independent oversight to the U.S. Army’s chemical weapons elimination program and serves as an important element in ensuring the safe destruction of chemical warfare material for protection of public health. The team’s focus is prevention with vigilance. The CDC’s responsibility for safe chemical warfare agent disposal falls into three categories: providing technical assistance, procedures for the safe disposal, and protecting public and worker health.

“Thus far, there have been no comprehensive scientific studies of potential risks to human health and the marine environment in specific areas of the ocean where chemical weapons were dumped off the coast of the United States. Therefore, it is difficult to provide definitive answers to questions about risks raised by public health and environmental advocates, marine conservationists, and the general public,” concluded the 2007 “U.S. Disposal of Chemical Weapons in the Ocean: Background and Issues for Congress”.

Munitions Debris

Military surplus electrical transformers, circuit breakers and other electrical equipment, referred to as munitions debris, also dumped in oceans, contains Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and International Research Agency on Cancer (IRAC), PCBs cause cancer and a number of serious non-cancer health effects on animals, including effects on the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system, and endocrine system. Because of PCBs’ environmental toxicity and classification as a persistent organic pollutant, the U.S. banned production in 1979 and, in 2001, the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants banned PCBs.

Consider Menhaden, an oily fish caught in the lower Chesapeake Bay as feeder fish for farm-raised salmon, which contain large amounts of PCBs from a Navy ghost fleet moored there. In addition, PCBs have resulted in young fish, especially cod, from reproducing and proliferating and thereby contributing to a decline in stocks. While the EPA classifies PCBs as probable human carcinogens, there is no evidence that PCBs cause cancer in humans at the low levels found in the environment.

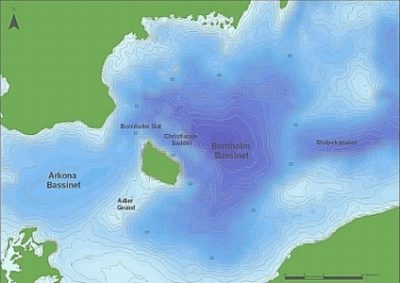

The Baltic Sea

The overall risk may be greater in the Bornholm Basin in the Baltic Sea, where post World War II disposal of the (Nazi) German stockpiles – 65,000 tons of chemical weapons and 17,000 tons of conventional munitions – were dumped by Russia, Great Britain and the U.S., and 33 ships containing PCBs were scuttled.

NATO’s Science for Peace and Security (SPS) project “Towards the Monitoring of Dumped Munitions Threat” is presently engaged in ongoing research, in conjunction with the Department of Environmental Science – Environmental Chemistry and Toxicology at Aarhus University, Denmark, as confirmed by Dr. Hans Sanderson, on the potential eco-toxicity and locomotion impact on zebrafish from the degradation of Sulfur mustard gas compounds, which were dumped in large quantities.

The Academic Community

As for the greater academic community, Dr. Porter commented that it, “…is only marginally aware of this issue. The broader field of “warfare-ecology” is beginning to draw some attention through NATO Workshops and several high pro-file publications in top-tier scientific publications such as Science, Nature, and Bioscience. However, other than a few stories about UWUXO hauled up in the nets of Baltic fishermen or washing up onto tourist beaches in New Jersey, the public is generally unaware of the magnitude of the problem. A vigorous free press will be the best antidote to this.”

Governance

While there are many existing protocols and conventions addressing explosive remnants of war (ERW) on land, such as landmines, there are only two international agreements as to underwater ordnance. First is the 1972 Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, referred to as the London Convention, developed to protect the marine environment. The second is the 2003 Protocol V of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, which requires that following active hostilities the parties must clear the areas under their control of ERW.

Many countries, such as Canada, the United States, Germany, Great Britain, Finland, Norway, Lithuania, Estonia, and the Netherlands, have enacted their own governing policies and procedures as to the removal or containment of conventional and chemical weapons, and military debris in their territorial waters.

In addition to clean-up sites, additional work to clear areas of UXO has been undertaken by governments, commercial companies and NGOs installing wind farms, or laying pipelines or cables on the ocean floor.

“The private sector or a government involved in a pipeline or green energy work avoids interaction with chemical weapons. As to conventional munitions, depending on the authorities, you have to work out a way to clear them through detonation or relocation. In some countries, such as the Netherlands, only the government can detonate, in others, such as Norway and Finland, private contractors can clear an area. When this occurs, there are environmental and mammal monitors to insure the least possible impact on marine life,” stated Simon Bonnell, partner of Stream Tec Solutions AG with many years worldwide experience including Nord Stream (NSP).

For instance, before detonating an UXO a fish clearing charge is set-off to clear the area of aquatic life as research, including that conducted on porpoises in the Netherlands, has shown that detonations can cause acoustical damage.

In addition to internal protocols, such as those used in laying the Nord Stream 1 pipeline through territorial waters, the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) has developed an international mine action standard (IMAS) for the underwater survey and clearance of UXO so as to mitigate the risks of underwater UXO and their attendant socio-economic impact. Using underwater equipment trials, the IMAS is a best practices guide – combining military tactics and mine action methodologies with commercial technology – on how to best clear underwater UXO in a safe, efficient and cost-effective manner.

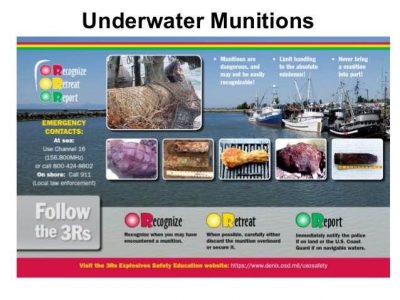

According to the GICHD, “Although underwater survey technology developed by the military and the oil and gas industry over the last decade has produced capable systems for mapping the presence of EO, the training, experience and qualifications required to conduct these operations can be substantial. Diving operations also require a considerable amount of training and experience. National authorities and donors need to decide early on which capabilities must be developed locally versus tasks that should be conducted by other organisations. The most tangible threat to humans has occurred through inadvertent or improper contact with an underwater conventional or chemical weapon.”

Most often individuals sustaining injury were engaged in dredging, laying pipelines, trawling, or installing wind farms.” A sampling of Incidents includes the following:

-

In July 1965 the fishing vessel Snoopy was trawling for scallops off the North Carolina coast when it caught a large cylinder-shaped item in its net. A long round object was spotted swaying in the net amid the ship followed by an explosion occurred killing all eight crew members and destroying the vessel.

-

In 2005 three Dutch fishermen were killed by a bomb that caught in their net which exploded on deck.

-

In 2011 45,000 people in Koblenz, Germany were evacuated when a drought revealed a unexploded device lying on the Rhine riverbed.

-

Since 2004, CDC documented three separate incidents of exposure to Sulfur mustard munitions. In one incident, a munition was found with ocean-dredged marine shells used to pave a driveway. The other two incidents involved commercial clam fishing operations.

In addition to the GICHD, there is another NGO, the International Dialogue on Underwater Munitions (IDUM), spearheaded and chaired by Mr. Long. “The IDUM is an internationally recognized body where all stakeholders (diplomats, government departments including external affairs, environmental protection and fishery departments, industry, fishermen, salvage divers, oil and gas, militaries and others) can come together in an open and transparent forum to discuss underwater munitions, seek solutions, and promote international teamwork on their issues related to underwater munitions. The IDUM promotes constructive engagement with all stakeholders rather than disengagement so that we may learn from one another’s situation.”

As there is no law governing the removal or containment of conventional and chemical weapons, and military debris in international waters and no uniform standard, and no map of all known sites, the IDUM has started a petition requiring 100,000 signatures for the issue of an international protocol to be discussed by the United Nations’ General Assembly.

“There is no national or international registry that can pinpoint where these dump sites are,” confirmed Dr. Porter.

“There needs to be heightened public awareness. The sea is polluted with massive amounts of explosives and they’re a danger to the environment for generations to come,” stated Arthur Hollmann, President of UXO Offshore Services, who works as Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) and former military Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) technician and diver.

Cynthia M. Lardner

Cynthia M. Lardner is a journalist focusing on geopolitics. Ms. Lardner is a contributing editor for Tuck Magazine and E – The Magazine for Today’s Executive Female Executive, and her blogs are read in over 37 countries. As a thought leader in the area of foreign policy, her philosophy is to collectively influence conscious global thinking. Ms. Lardner holds degrees in journalism, law, and counseling psychology.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!