AP photo

By

Rupen Savoulian

In an article for The Conversation, Daryl Adair, a professor of Sport Management at the University of Technology, Sydney, makes a pertinent observation regarding the interaction between sport and politics:

It is sometimes said that sport ought to be separate from politics, or that politics should be removed from sport. These sentiments are well meaning – if idealistic.

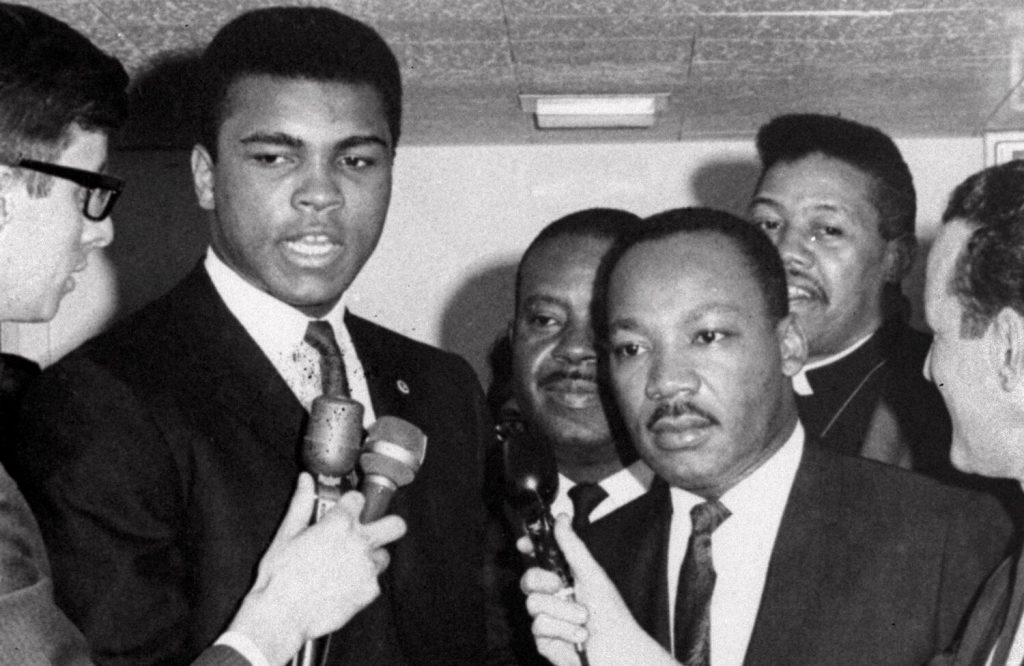

In his article, called “Sit on hands or take a stand: why athletes have always been political players“, Adair makes the case that high-profile athletes and sportspeople cannot remain indifferent to the wider social and political issues in which the practice of sport occurs. Sport, being an activity that is simultaneously part of government policy, commercial money-making, health and fitness issues and leisure-time entertainment, has been regarded as largely insulated from the cultural, social and political issues in the wider society. Athletes such as the late Muhammad Ali, basically rewrote the rules surrounding the engagement of celebrity-sportspeople with the political issues that predominate during their lifetimes.

Ali not only proved himself to be the best in his chosen sport, but used his high-profile to raise awareness about the plight of the African American community, and express his views on the larger social and political issues of his time, such as America’s intervention in Vietnam. He was certainly attacked at the time for his views, and became a widely reviled figure in the 1960s and 70s. While Ali was subsequently admired for this stand against racism and war, his image has been largely hollowed out of its overtly political and social content. It may be true that Ali preached love for everyone, and hatred for no-one: but that is only a shallow understanding of the issues for which he stood, and the politically radicalised stand he adopted.

Sport has largely been seen as a ‘level-playing field’, an arena in which any person, regardless of their race, creed, ethnic background, gender or beliefs can succeed, depending solely on their talent and dedication to the sport of their choosing. Sport is such an integral part of the Australian psyche, and there are reams of commentary about the importance of sporting people in defining our national character – if we have any such character. Sporting professionals are described as ‘heroes’ and role models for our youth. They are strongly condemned for any indiscretions on or off the sporting field.

Sport is a crucial part of schooling, an activity that builds character and through which social connections are formed. In Sydney, the rugby league is the definitive football code – Melbourne had the Australian Rules Football. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, as the two codes expanded nationally, those lines have been blurred. However, make no mistake – the ‘footy’ faces strong competition from the cricket competition; the most successful Australian cricketers are national celebrities, and their words are heavily promoted in the corporate media. The soccer, once dismissed derisively by the Anglo-Saxon establishment as the ‘wog ball’, is now a national competition, and the Socceroos have an enthusiastic and growing fanbase.

However, when it comes to political issues, sportspeople are facing a contradiction. Their high-profile enables them to comment and contribute on a wide range of issues; but we object when they run counter to the prevailing sociopolitical consensus. As Professor Adair elaborated in his article earlier:

The off-field contributions of many athletes, such as by contributing to charities or virtuous social causes, are rarely the subject of media discussion. There is, nonetheless, much more public interest should an athlete present a dissenting perspective in respect of a sociopolitical issue via sport.

Negative refrains typically include: athletes should “stick to sport”; that they are “using sport” to advance a political agenda; and (like other celebrities) they are not credible advocates because they live in an elitist “bubble”.

Peter Norman – the white man in the Black Power photo

Peter Norman was the Australian sprinter and athlete who took the silver medal in the 200 metres race during the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. However, he is best known for standing in solidarity with Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the African American athletes who raised their fists in the black power salute while on the Olympic dais. The story of Smith and Carlos has been told repeatedly; Norman’s is less well known, even though he is in many ways an equal hero on that fateful day in 1968.

Norman was originally an Australian Rules Football fan, and that was his first passion. However, he was a talented sprinter, and qualified for the Australian team. In the 1960s, a group of American athletes formed an informal activist group called Olympic Project for Human Rights. They were concerned about the racism and violence directed against the African American community. These athletes, after prolonged debate, decided to participate in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. However, each athlete, was encouraged to follow their individual conscience to protest the appalling conditions afflicting their communities in their own way.

Smith and Carlos, members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, decided that first, they would accept their medals shoeless to indicate the poverty in which the majority of African Americans live. Second, they decided to raise their fists in the black power salute, knowing full well the heavy consequences should they do so. Both had expected to win gold and silver respectively; but roaring up out of the Antipodes, Peter Norman blitzed the field, and ran in second. Olympic observers were stunned – who is this mysterious speedster from Australia?

In the 1960s, Australia had in place a series of restrictive laws on the indigenous population, almost akin to apartheid South Africa. Former long-term prime minister of Australia, Robert Menzies, publicly defended apartheid South Africa, and stated those types of racially-restrictive laws were necessary for that country. Australia could hardly be described as a model of tolerance and diversity at the time. Norman, coming from a country that had similarly regressive laws curtailing the rights of the indigenous people, was an anti-racism advocate. However, no-one predicted the strong stand he would take in 1968.

Not only did Norman wear the Olympic Project for Human Rights badge while on the dais accepting his medal, he also asked Carlos and Smith for a pair of black gloves to wear. When told that their was only pair between them, Norman suggested that they should wear one each. They took his advice. Norman stood in solidarity with his fellow athletes. Carlos and Smith wore one black glove each.

For that stand, and for that act of solidarity, Norman would pay for the rest of his life. Norman, though qualifying numerous times for a spot on the Australian team for the 1972 Munich Olympics, was excluded. He retired from athletics soon after. He never ran competitively for Australia ever again. He died of natural causes, ostracised by the wider sporting community, in 2006.

As the writer Riccardo Gazzaniga wrote in an article in 2015 examining the life of Peter Norman:

Back in the change-resisting, whitewashed Australia he was treated like an outsider, his family outcast, and work impossible to find. For a time he worked as a gym teacher, continuing to struggle against inequalities as a trade unionist and occasionally working in a butcher shop. An injury caused Norman to contract gangrene which led to issues with depression and alcoholism.

As John Carlos said, “If we were getting beat up, Peter was facing an entire country and suffering alone.” For years Norman had only one chance to save himself: he was invited to condemn his co-athletes, John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s gesture in exchange for a pardon from the system that ostracized him.

A pardon that would have allowed him to find a stable job through the Australian Olympic Committee and be part of the organization of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Norman never gave in and never condemned the choice of the two Americans.

Norman, who passed away in 2006, stayed true to his conscience, and always expressed his support for his friends and fellow athletes from the United States. When he died, it was Carlos and Smith who carried Norman’s coffin to its final resting place. Norman was issued a posthumous apology by the Australian Federal Parliament in 2012. The move to apologise to Norman was driven, not by the Australian Olympic Committee or any sporting body, but by a concerned MP. The fact that the apology was so late in coming, and not sponsored or promoted by any athletic organisation, must raise serious questions about the state of race relations in Australia today.

Athletes do not exist in a political and social vacuum

Let us end the fiction that sport and politics are mutually exclusive. When Colin Kaepernick refused to stand for the American national anthem, he did so because he fully understands the problems of police violence and poverty that afflict the African American community. Kaepernick has faced a serious backlash against his actions, precisely because he deliberately stepped outside the bounds of what is considered acceptable political conduct by a prominent black American athlete. He is no Michael Jordan – the latter, a submissive superstar, a value-free brand salesperson.

Actually it is not correct to refer to Jordan as value-free, because he does stand for a certain set of ideals – those of the corporate sponsor. Jordan, the spokesperson for Nike, declined to take a stand on important social and political issues, because it would threaten shoe sales. Jordan declined to support a black Democrat candidate, on the basis that the Republicans are customers of Nike as well. I suppose being a shoe salesman was more important than tackling issues of racism.

Jordan, and O J Simpson, prior to his murderous rampage – are the archetypes of the non-political, bland corporatised athletes – with black faces. They are effective at selling their brand – clean-cut, articulate and suave, but also non-challenging to the racially stratified capitalist system. Yes, O J Simpson was the perfect superstar – a talented footballer, and smooth corporate frontman, and indifferent to the momentous economic and political challenges faced by African American communities.

When Peter Norman was asked, years later, about the stand he took with Carlos and Smith, he stated:

I couldn’t see why a black man couldn’t drink the same water from a water fountain, take the same bus or go to the same school as a white man.

There was a social injustice that I couldn’t do anything about from where I was, but I certainly hated it.

It has been said that sharing my silver medal with that incident on the victory dais detracted from my performance.

On the contrary.

I have to confess, I was rather proud to be part of it”.

Athletic and sporting achievements are definitely worthy of admiration and respect; taking a stand in solidarity with the oppressed is no less admirable and inspirational.

Rupen Savoulian

I am an activist, writer, socialist and IT professional. Born to Egyptian-Armenian parents in Sydney, Australia, my interests include social justice, anti-racism, economic equality and human rights.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!