By

Malinda Seneviratne

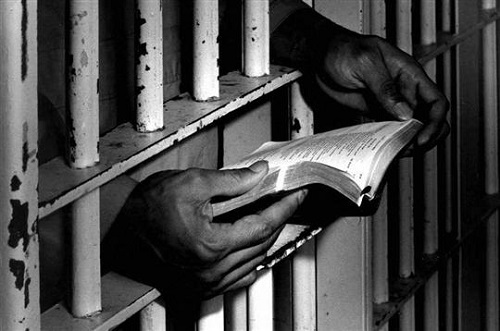

Prisons are not exactly city attractions. They are somber edifices with high walls and barbed wire. We might see them as we pass but our eyes don’t tarry, they move to other and more pleasant objects for perusal. The word prison anyway is uninviting. If the Welikada Prison is an exception to all this it is because of the impressive mural that adorns the wall that faces Base Line Road and especially the bold trilingual affirmation, ‘Prisoners are human beings.’

Yes, they are, although they are not viewed with adoration. They are there because they’ve broken rules and are considered to be threats to society’s general well-being. They are there because they have to pay a price for wrongs they have done. They have to do time. And once society has exacted adequate compensation or rather when society deems that they’ve repented, reformed and are rehabilitated enough, they get to go home, they get to re-enter society.

It takes years for the past to be erased from society’s memory and of course the memory of the wrongdoer. Or never, one might add. Of course there are some crimes that are harder than others to forget or forgive, but then again, there are many, many cases where infringement not only brings a prison sentence but also (further) criminalizes the perpetrator in addition to compromising the mental well being of the inmates.

That’s not all. As Albert Camus observed in his celebrated essay against capital punishment for society to pass judgment (through the courts) on anyone, society has to be fundamentally good. That might be taken to be a bit extreme, but if you think about it, in an imperfect society where rules are bent by the powerful, there are probably as many criminals outside prisons than inside them.

But let’s keep ‘society’ out of it. There are no perfect societies, after all. The question is, are there perfect justice systems and are there prisons which can truly claim to treat each and every inmate as human beings?

I remember vividly a ‘court moment’ 25 years ago. It was at the Panadura High Court. A group of around 15 young people were on trial for sedition and were locked up in the court cell (or whatever it is called) until their case came up. In that same ‘waiting facility’ there was a young couple. The woman had been working as a domestic aide in a house. The man of the house, according to her story, had tried to sexually molest her. At that very moment her husband had arrived (for whatever reason). Livid (according to his story), he had attacked the would-be rapist and killed him.

Their case came up. The state-appointed lawyer arrived and claimed he had a bad stomach and pleaded for a different date. The judge obliged; the case was postponed for six months. Just like that, six months were taken from the lives of two individuals who, we are told, are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

That’s just a simple story that illustrates just one element of a whole gamut of problems with the justice system. The arbitrariness of releasing suspects on bail, inconsistency in sentencing, privileging of the powerful and not least of all the frivolous nature of pardons leave much to be desired.

Let’s get back to prisons. It is not that prisoners are treated like animals. We need to take into account the lack of adequate resources, outdated regulations and rank corruption, all of which are of course not the preserve of the Department of Prisons. National-stink, if you may, wafts all over and prisons, for all their security measures are not impervious.

So yes, things are not easy for the authorities. There are all kinds of programs in prisons which draw from the assertion on the Welikada wall. Prisoner education is an important part of the process, for example. And yet, there’s a lot that can be done despite the constraints.

The state and therefore the people pay for prison costs. Sri Lanka does not have private prisons and the state cannot be described as yet in terms of a prison-industrial complex. The costs cannot be fully recovered by value extracted from prisoners. However, if every rupee counts, then prisoners could be seen not just as human beings but as human resources.

Is the human capital that’s within prison walls being used effectively, is a question that needs to be asked. While prisoners can be categorized in terms of the nature of the crime, the severity of sentence, race, religion, age, etc., they can also be divided in terms of educational attainment and the skills they possess, all of which are meticulously documented.

There are literally thousands of prisoners who have passed their A/Ls. A significant proportion are probably endowed with specialized skills. While it is not possible, obviously, to turn prisons into ‘economic units’ it is nevertheless worth exploring areas where the quantum of skills can be deployed effectively. There’s value that can be obtained and most importantly such measures would invariably have a positive impact on the mental wellbeing of the inmates.

One cannot but recall how ex-combatants were rehabilitated, given opportunities to further their education and acquire skills, and then reintegrated into society. In many instances their ‘crimes’ were far more serious than those of thousands who languish in the prison system.

If it was ok for ‘terrorists,’ why not for others, one might ask. And it’s not just people with A/L qualifications. There are graduates, even inmates, who had post-graduate qualifications.

One is reminded of the film ‘The Shawshank Redemption’ where the expertise of a banker, wrongfully convicted of murder, is used by the prison warden for money laundering operations. That’s fiction and the deployment of the relevant expertise was for unlawful activity. However, what the movie also tells us is that there are inmates with exceptional skills that are either not fully used or ill-used or even ignored altogether.

There’s utter inefficiency, randomness and possibly even corruption in the parole process. Prisoners are interviewed, judgement passed and when committees change the entire process is started from scratch. There should be a way to fast-track things. There should be a way to monitor the progress of each and every prisoner in the rehabilitation process that has been encrypted into the prison system. Good behavior, proven efforts to better oneself in terms of skill and knowledge acquisition, etc., should be factored in systematically. This does not of course mean that the educated prisoner is somehow of a higher moral worth than the rest, but that’s not what we are talking about. It’s about resource-waste.

In any event, ’Ad hoc’ is never good enough, even if resources are lacking.

The film has a scene where a prisoner goes before a parole committee. The stress is on the arbitrary nature of arriving at a decision. Just like in the Panadura court. Months are taken away from people’s lives, years too.

What all this calls for is a complete review of the prison system. There are good officers. There are excellent programs concerning prisoner welfare and rehabilitation. There’s a lot of good work being done. It’s not enough.

Prisoners, let us repeat, are human beings. They constitute part of the nation’s complement of human resources. They are in prison for a reason, and the state weighs opportunity costs against opportunity benefits when determining to sustain them in prisons over letting them loose on society. All this is understandable. But if it is about ‘understanding’ then what needs to be taken cognizance of is the fact that people can become better just as they can become worse; and those who fall into the former category should be treated differently, encouraged, and employed in ways that make sense given their knowledge and skills.

Perhaps the ministers overseeing the subjects of justice and prisons can do something to streamline things, to rationalize the entire system and to give more credence to the dictum scrawled on the wall of the Welikada Prison.

Malinda Seneviratne

I am a journalist, political commentator and a chess enthusiast. I was educated at the University of Peradeniya, Harvard University, University of Southern California and Cornell University and live in and work from Kottawa, Sri Lanka.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!