Solomon Tembang photo

By

Solomon Tembang

Nagbayanga Valentin, a widow in her late thirties, sits on the earth floor of her thatched two-roomed house she shares with her four young children in Haya Haya, a mining encampment with about 2,000 inhabitants in Longa Mali village of Betare Oya sub division, some 200 kilometres from Bertoua, headquarters of Cameroon’s East region.

Dirty pots, pans and other old household paraphernalia are strewn all over the tiny house. Outside, the laughter and chatter of her children and those of other neighbours is audible enough as they play a local game, virtually ignorant of the weighty problems their mother, and the community, are going through.

Poverty is discernible in the community whose inhabitants live in thatch houses, but just metres away, Chinese machines are rumbling as they mine away millions of francs CFA in gold.

Conflicts had, over the years, been brewing between the local population and Chinese miners until it boiled over on November 15, 2017 when there was a confrontation and a Chinese worker pulled out a gun, shot and killed a local. The population rose up in anger and beat the Chinese man to death. Since then, relations between the local community and the Chinese miners have been frosty as tension continues to simmer.

“My husband was shot and killed by a Chinese and now I am left with four children to fend for,” Nagbayanga Valentin says. “Things are not easy as life is becoming very difficult in this community. The little money my husband made from artisanal mining is no longer there and so I wonder how I am going to feed these children or even send them to school.”

Her husband, Issa Paul, was shot dead by a Chinese worker whom the locals simply knew as Bouboul.

Chinese worker who was lynched by the local population of Haya Haya after he shot and killed a local artisanal miner – Photo – FODER

Beleke Andre, brother to Issa Paul, was there when it all happened.

“We were seven of us digging in our hole. The Chinese also had their hole not far from ours. But later, the Chinese, maybe realising that our hole was producing more gold, insisted that they must dig where we were already working. As they continued to insist, we said they should wait since we had our ‘stones’ in the hole and when we take them out, they can go ahead,” Beleke Andre says.

“They wanted to pay us money to take over where we had been digging. But we said since we were seven of us, they should wait until we agree among ourselves before we can strike any deal with them. That is how we continued digging to take out our ‘stone’. But the Chinese, whom many villagers simply called Bouboul, we don’t even know his real name, was insisting on closing the hole. When we did not allow him close the hole, he called the Chinese camp, which is close by, on the telephone.”

“Three Chinese then arrived at the scene. At this moment, Bouboul went to one of their vehicles, took a gun and shot three times in the air. When he came close, I am the person he wanted to shoot. As my pregnant wife was also at the scene, I went and stood behind her.”

“Bouboul then fired another shot in the air and then shot at my elder brother, Issa Paul. As my brother died, we overpowered the Chinese and took the gun. All I remember is the population coming out in anger and beating the Chinese who later died.”

The case has been dragging at the judiciary and the chances for them to find justice over the death of their loved one, Beleke says, are very slim. He says at the court, the Chinese maintain that if they have to pay for the death of the Issa Paul, the locals also have to pay for the death of the Chinese.

“But we are not the ones who started the conflict. He was the one who first shot and killed our brother,” Beleke laments.

Locals carrying out artisanal mining in eastern Cameroon – Photo – Solomon Tembang

‘This land is our livelihood’

Some of the locals have been mining in this area for decades after inheriting the land from their forefathers in accord with local traditional law (droit coutumier), only for them to get up one day and see the Chinese brandishing a mining concession on their land.

This was the case with Doko Habraham in Colomine, some 100 kilometres from Betare Oya.

“This land is our livelihood. If taken away from us and given to the Chinese we won’t have any other means of earning a living. My ancestors have been on this land for several decades. I went to where my mine was one day, and it was like I wasn’t even on my own land anymore,” Doko says.

“No one came to tell me that my land was going to be taken over by Chinese miners and if I was going to be compensated for the said land,” he adds.

Doko Habraham says he later found out that the Chinese miners who were working with machines on his land had bought a concession from a Cameroonian who had secured exploration rights in the area. Doko has no land title and so he is no match to the Chinese miners, whom, he claims, “could easily buy their way around.”

Panning for gold poses little threat to the environment – Photo – Solomon Tembang

How the Chinese miners came here

For years, the local people had been mining for gold on their ancestral lands, through artisanal means using spades, buckets and hard work until the Chinese companies arrived with excavators and powerful pumps and are now practicing semi-mechanised mining. The Chinese have been devastating the environment and the locals say they’ve received no compensation.

The Chinese are in brisk business, mining away hundreds of millions of francs CFA in gold. But those bearing the brunt of the mining bonanza are the native communities who continue to live on the edge of the precipice.

But how did the Chinese come about carrying out semi-mechanised mining in this area? Justin Chekoua of Non Governmental Organisation, Forêt et Développement Rurale, FODER, working in the area, explains that semi-mechanised mining came to the East region of Cameroon in early 2000 when the Cameroon government was planning to build the Lom Panga hydroelectric dam. He says when the government realised that a lot of gold would be lost in the area that was going to be flooded by the dam, it set up what was christened “Programme to Save Gold in Lom Panga Dam Area”.

Cameroon’s mining code does not allow non-nationals to acquire mining authorisation for concession areas. Chekoua explains that because the artisanal miners would have been slow and not be able to save all the gold before the dam floods the area, the government allowed semi-mechanised mining to be carried out.

“But since the nationals carrying out artisanal mining did not have the expertise and finance to save the gold speedily through semi-mechanised mining, the government said Cameroonians could enter into technico-financial partnership with expatriates. That is how many Cameroonians brought in expatriates, majority of who are Chinese, to come into partnership,” Chekoua discloses.

The authorities conceded the move would violate mining laws but said the situation was an emergency.

“However, instead of going into technico-financial partnership with expatriates for the semi-mechanised mining, Cameroonians are now instead getting the authorisation and selling to the Chinese. They are now selling mining space to Chinese,” Chekoua regrets.

He elucidates that because the area around the Lom Panga Dam was going to be flooded, the semi-mechanised miners were not compelled to carry out any environmental impact assessment. They were also not forced to fill the holes their activities left behind.

“The mining code specified that each individual could have a maximum of four hectares to mine in…and instead of staying within the area where gold was to be saved, those who are acquiring authorisation and their Chinese ‘partners’ have gone beyond this zone,” Chekoua adds.

Roads deteriorating in the mining areas – Photo – Solomon Tembang

Environmental hazards

Since the Chinese miners went beyond the area to save the Lom Panga gold, the environment and local communities have continued to suffer.

“Previously when the locals were carrying out artisanal mining, there was little or no impact on the environment. But since the Chinese came in with semi-mechanised mining, the environment has been devastated,” Chekoua says.

Many waterways have been disrupted and streams silted.

“Because the Chinese need a lot of water to carry out the semi-mechanised mining, they have deviated almost all the streams or rivers into their mining camps and local communities downstream have no water for household and other uses,” Justin Chekoua notes, adding: “In some areas such as Longa Mali and Ngoe Ngoe, mud from the activities of the Chinese miners has silted streams and rivers. The use of mercury by the Chinese miners has also polluted streams and rivers. Fish and other aquatic animals are dying. Oil and petrol from the Chinese machines are also polluting streams.”

Pristine forest is also being cut down to make way for the Chinese mining activities.

Loud, vibrating sounds of excavators accompany the back-breaking work of the mine workers, just a kilometre outside of Colomine. Covered in mud, they sway around in the mining pits as they pan for gold, dig more holes, or use the noisy machines on the edges of the mining pit to fill trucks with quantities of the gold-containing mud that will later be processed with mercury. At this exact spot, there used to be a forest, but many layers of vegetation have already been removed by miners.

There is no possible coexistence between mining and forests, says Justin Chekoua. “All lands dedicated to mining, and in particular to surface mining, will be a terrain where forests are sacrificed because it requires the removal of large amounts of land. This sacrifice of the forests represents an irreparable loss of natural capital.”

Locals live in poverty while Chinese mine away billions in gold – Photo – Solomon Tembang

‘Misery is our potion’

Despite all the millions of francs CFA being mined away in gold, the inhabitants of these localities are living in abject poverty and lack the most basic of social amenities.

Hamadgoulde Bouba, the traditional head of the Haya Haya settlement, is not a happy man.

“We don’t have water. Where they throw their sand was where we used to fetch water. Now they have blocked it. Other places we have created to get water they have also destroyed them. Even the road is deplorable. Their trucks have completely destroyed the roads. In fact, all we know here is misery,” he laments.

“They do very little for the population. And to worsen things sometimes, we go to our farm only to discover that the farms have disappeared, with the soil having been dug by the Chinese and taken away to their camp to wash and get gold. How do we live if our farms are being destroyed?”

Many inhabitants of Haya Haya refused to talk on record, saying they were afraid of being victimised by the Chinese. The Chinese have instilled fear in the inhabitants of Haya Haya. One simply said “the fear of the Chinese here is the beginning of wisdom.”

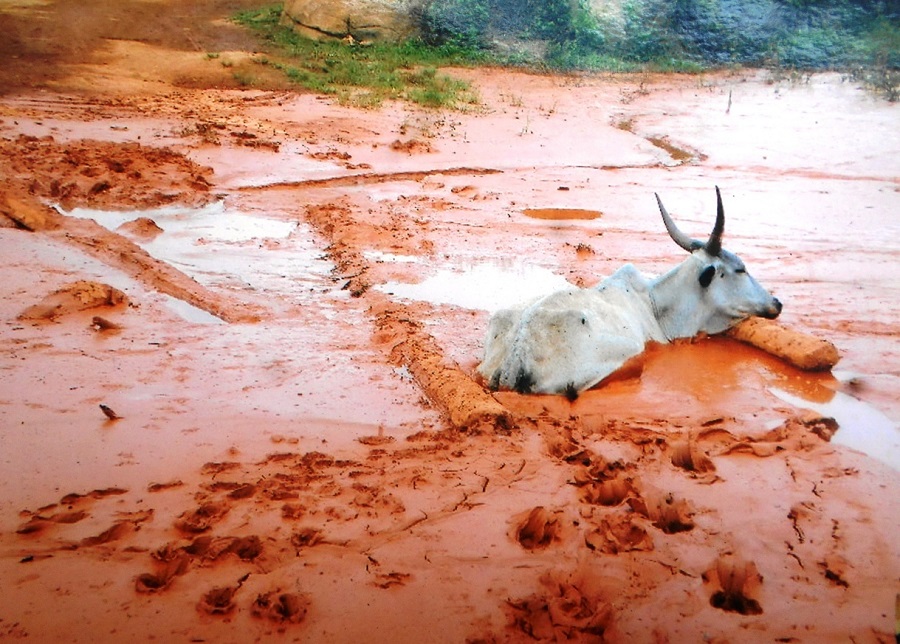

Deadly pools left behind by Chinese miners – Photo – Solomon Tembang

Deadly open tombs

The semi-mechanised mining activities of the Chinese have left behind deep holes which have been filled with water. The localities of Longa Mali, Colomine, Ngoe Ngoe, Ngoura, Ngoyla, Batouri, Yokadouma are littered with such holes, some as deep as 50 metres, many of which have been filled with water.

People are said to have lost their lives in these deadly tombs. According to statistics from FODER, at least 47 persons died in 2017 on the former mining sites. About 250 mining sites opened between 2012 and 2014 have not been filled, the NGO added.

Cattle and other livestock have also been falling into these holes, locals say.

“We cannot even rear livestock because they will all fall into the holes Chinese miners have dug everywhere. The situation is very pathetic,” Hamadgoulde Bouba says.

Pilo Michel, traditional ruler of Longa Mali says Chinese miners have devastated his community – Photo: Solomon Tembang

No compensation

According to Cameroonian law, the mining companies are supposed to pay compensation to local people who owned or were making a living on the land.

But Pilo Michel, traditional ruler of Longa Mali, says there is nothing to write home about the activities of Chinese miners in the area.

“They have not done anything good for my village that they are exploiting. The state of the road to the village is bad. I don’t know of what use the Chinese are here,” he says.

“Since the days of my parents before I took over as chief, the Chinese have done nothing here in terms of corporate social responsibility; not a school, not a health centre, not water supply, not even to repair the road they use to evacuate what they mine here. They have instead continued to destroy sources of livelihood in our village. They continue to exploit us. Longa Mali village is rich in minerals but has nothing to show for it,” Pilo regrets.

“Even the holes they dug, they have not refilled. Water has filled these holes and they are posing real danger to the community. People have been dying in those holes.”

Pilo says the government of Cameroon must force the Chinese miners to construct schools, health centres, repair the road and provide potable water to the community and even build a market.

As for the open tombs they have left, Pilo says: “they should fill them. We insist on the Chinese closing these holes they have dug, if not, humans and livestock will continue falling into them.”

These women and children may lose their home due to mining activities – Photo – Solomon Tembang

‘We may be rendered homeless’

Rajahu Alahji Oumarou, a 21-year-old mother of two children stands at the doorway of her three-room thatched house in the Zirgene neighbourhood of Colomine, lost in thought. Just 10 metres away, bulldozers belonging to Chinese miners are working in a huge hole. While the excavators continue to dig the over 70 metres deep hole, trucks stand by ready to be loaded with the soil which is carted away to the Chinese miners’ camp to be washed for gold.

Like others who make up the 71 households in Zirgene, Rajahu’s forefathers lived in the area for decades. But now she says they, mostly of the Mbororo minority ethnic group, are about to be rendered homeless. Their thatched houses, which now perch on the edge of the large hole, may end up falling in. To add to this, children and even adults run the risk of falling into the hole which may end up being filled with water.

“I am not happy seeing this. My child almost fell into the hole the other day. If I was not vigilant to rush and hold him from behind, it would have been a different story,” Rajahu recounts.

Oumoul Abdou, a 27-year-old mother of four laments; “we are living in fear as we stare death in the face on a daily bases. There are several of these holes surrounding where we live. We can no longer use our latrine because a hole dug by the Chinese miners has ‘cut it off’. They destroyed our groundnut farm when they dug one of the holes.”

Local youth blocking a truck belonging to Chinese miners after clash between the locals and the Chinese over a mining area – Photo – Solomon Tembang

‘This hole belongs to us’

As I talked to Rajahu and Oumoul, I hear loud arguments coming from where the bulldozers were digging. When I got there, I found out that the machines had stopped working. A group of local youths gathered around and were in a heated argument with the workers of the Chinese miners. Some of the youth had used logs of wood to block the loaded trucks from leaving and others from coming in.

Some of the youth were claiming that they have been carrying out artisanal mining here to earn a living and now, the Chinese have come with machines and want to take over the place.

“If they want to continue their activity here, they must compensate us financially. This area belongs to us,” some of the youths shouted.

The situation, which almost led to a brawl, was only brought under control when an elderly man from the Colomine community, after negotiation with the Chinese through their interpreter, assured the youth that they will be compensated the next day. But one of the youngsters told me such promises have been made severally but never kept.

Such clashes between the Chinese and the locals, Honore Sirgho, a local vigilante leader says, are the order of the day.

On the opposite end of the town, some pupils of Government Primary School Colomine are playing football behind one of the classrooms. But less than 60 metres away is a hole, about 30 metres deep, that has been dug by miners. Some of the pupils say they are aware of the danger the hole poses, but have learned to live with it.

Officials of the school, which counts some 1,400 pupils, were not available for comment.

This hole was dug by miners just a few metres away from Government Primary School Colomine – Photo – Solomon Tembang

Deathtraps

The mining activities have also left behind deathtraps in some areas like Ngoe Ngoe, a village in East Cameroon with about 2,600 inhabitants. In the night of January 1, 2017, nine people were killed in an abandoned mining site when they went in search of gold. The site collapsed and buried them in 33 feet of earth in the mine excavated by Lu and Lang, a Chinese mining company banned from operating in Cameroon in April because it lacked a license.

Yaya Moussa, head of Ngoe Ngoe village, recounts the tragedy.

“The Chinese arrived with [Cameroonian] law enforcement to drive the villagers out of the mine sites to better exploit our resources,” he explained. “So the villagers were forced to come in the night, in the absence of the Chinese, to extract gold and find food for their families. It was during one of these nocturnal outings that the earth fell on them.”

However, the deaths in this particular gold mine in Ngoe Ngoe have not deterred locals from venturing into it. When I visited the area in October 2018, some young men could still be seen digging in the ill-fated pit in search of the precious stone.

Oumarou Haman, president of the Ngoe Ngoe vigilante group, says the lure for gold still attracts people to the mine site, which is yet to be rehabilitated.

“If nothing is done to refill this site, I fear that many will still die there,” he says.

Semi-mechanised mining – Photo – Solomon Tembang

Students drop school to chase gold

The lure of the gold is also having a toll on school attendance in the East region of Cameroon. Justin Chekoua says many students are dropping out of school to go to the sites that have not been refilled or closed by the Chinese miners to dig for gold. Women, some pregnant and others with babies on their backs, are also attracted to the mining sites.

Government authorities have told locals to stop digging in the abandoned sites. But the need for income is so high that many ignore the order, including kids who should be in school.

Yves Bertrand Awounfack, Senior Divisional Officer of the Lom and Djerem Division, sometime ago, launched a drive during which he went from village-to-village asking locals to leave gold mines alone and for parents to return their child miners to school.

Vincent Atangana, a Cameroonian official at Chinese mining firm EXXIL, blames parents for allowing their kids to work in the mines. He argues Chinese mining has helped develop the area.

He says many houses are being constructed with modern materials. Several years ago, fuel was sold in cans but today, says Atangana, there are fuel stations. He says these developments are coming when gold mining is still at a working stage – they will do even more when it reaches the industrial level.

East region of Cameroon is ridden with such pools left behind by miners – Photo – Solomon Tembang

Billions of francs CFA in gold lost

Under Cameroonian law, minerals in the ground belong to the state. The state grants concessions to mining companies in return for 15 percent of the gold they extract.

This 15 percent is supposed to be paid to a state-owned institution known as Artisan Mining Support and Promotion Framework with French acronym CAPAM. But Justine Chekoua of FODER says some of the miners declare less than what they mine, causing the Cameroon government losses in billions of francs CFA.

On January 8, 2018, CAPAM declared that in 2017, it channeled a little more than 255 kg of gold to Cameroon’s Ministry of Finance.

Cow stuck in one of the holes left by Chinese miners – Photo – Solomon Tembang

‘Sad situation’

Nyassi Tchakounte Lucain, Executive Director of Transparency International Cameroon says they have read several reports from NGOs in the area about the deadly holes left behind by the miners.

“It is a very sad situation. We hope that while undergoing a deep study on the situation especially on the issue of transparency, we would be able to come back with concrete information and results about what is actually going on and what we can propose as a civil society organisation,” he says.

As to holes left behind by miners Nyassi says “if verified, I will call on the government of Cameroon to ensure that the laws are applied for these holes to be filled because the government is the guarantor of the security of humans and properties.”

Stream silted by activities of Chinese miners – Photo – Solomon Tembang

‘We can’t encourage destruction of environment’

Meanwhile, Ndouop Njikan Ibrahim of Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, EITI Cameroon Permanent Secretariat, says: “I have myself been to some of these areas where semi-mechanised mining is being carried out by the Chinese and I discovered that the activities are very harmful to the environment.”

“EITI has the objective to better the lives of the population and we cannot do so by encouraging the destruction of the environment. So we persuade mining enterprises to respect the norms of environmental protection. We regret the fact that the local authorities in these areas, who should be acting like watchdogs, are not doing so,” Ndouop says.

“It is also regrettable that most of the Chinese miners are not acting through formal and identifiable enterprises in a direct relationship with the state. Most of them have got the authorisation to act on the field after having bought the license that an individual happened to have acquired from the administration. Now that the license acquired by an individual has been sold to another person, who is responsible for the environmental destruction? That is the issue that should be handled by the state. EITI Cameroon can only act like a whistleblower to indicate that there is a problem here that should be resolved or it may deteriorate the living condition of the local populations.”

On the losses the government suffers financially Ndouop says: “the only way the government can control quantities of gold mined is to go into commercial relationships with formal, identifiable companies on the field. The government should create and multiply control instances.”

While some of the Chinese miners who were suspended by the government have continued in deviance, Ndouop blames this on “laxity” on the part of administrative authorities.

“The Chinese are doing this in complicity with Cameroonians,” Ndouop states. “Something really has to me done in the semi-mechanised mining sector as it was done with the petroleum sector.”

Semi-mechanised mining posing threats to the environment – Photo – Solomon Tembang

Need for strict regulation

On her part, Evelyne Tsagué, Africa Co-Director of Natural Resource Governance Institute, says: “from the work that we have been doing, we know that the semi-mechanised mining sector in Cameroon has a lot of problems; the problem of impact, regulation, problem of effectiveness of the rule in place. There is the need to strictly regulate activities in the semi-mechanised mining sector.”

“There is a huge gap between the mining rule and what is practiced. The government should ensure that if a regulation already exists to guide activities of people in the mining sector, this should be respected to the letter. Where there is no rule, the government should pass a law so that there is a kind of policy and regulation in this sector,” Tsagué notes.

Gov’t moves to stem the tides

However, the government of Cameroon has not been lying on its laurels. It has taken several steps to stem the tides as far as the activities of the Chinese miners are concerned.

In April 2018, the Minister of Mines, Industries and Technological Development suspended the activities of three Chinese mining companies for non-compliance to regulations.

In a statement suspending Hong Kong, Peace Mining and Lu and Lang companies, the minister said they were no longer allowed to perform gold mining activities in the East region of Cameroon, and that their officials have been asked to pack their bags and leave.

It appeared from the statement that Hong Kong Company did not have documents authorising it to carry out mining activities while Peace Mining and Lu and Lang companies’ suspension was linked to a series of conflicts recorded between their employees and local populations which resulted in deaths, in addition to the non-respect of the environment, according to the statement.

Cameroonian government mining officials said they are trying to address the situation by using drones to investigate claims of other illegal mines, according to two officials who asked to remain anonymous because they did not have permission to speak to the press. They also said most of the Chinese mining companies do not have permission to work in the country.

The divisional delegate of mines for Lom and Djerem division, East region of Cameroon, William Djoulde, says artisanal mining contributes significantly to the national economy. He says there are over 20 authorisations and with the measures being put in place, many clandestine miners will be flushed out.

“We want to professionalize this sector and send away clandestine miners who help neither the state nor the local populations. The measures are being implanted in the field,” Djoulde adds.

* This work was produced as a result of a grant provided by the Africa-China Reporting Project managed by the Journalism Department of the University of the Witwatersrand.

Solomon Tembang

Solomon Tembang is a Cameroonian development and investigative journalist with several years experience. Based in Cameroon’s capital, Yaounde, he has a wide knowledge and mastery of critical issues concerning his country. Solomon covers politics, conservation, agriculture, water and sanitation, extractive industries, women and land rights, climate change, health, economy, etc. He has the ability to give local issues a global perspective.

He can be contacted at [email protected]. Tel/WhatsApp: (237) 679359872

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!