Dr. John Colarusso is a world renowned Professor of Linguistics and Mythology whose long standing area of interest has been the Caucasus. When acting as an adviser to the Bill Clinton administration on the wars in the Caucasus, he was instrumental in starting a plastic surgery programme for women who were injured from both sides of the Abkhazian – Georgian War. In an interview with Saida Panesh, Dr. Colarusso discussed his scientific research into the language of the Circassians, a mysterious group of people aboriginal to Sochi, host of the 2014 Winter Olympics.

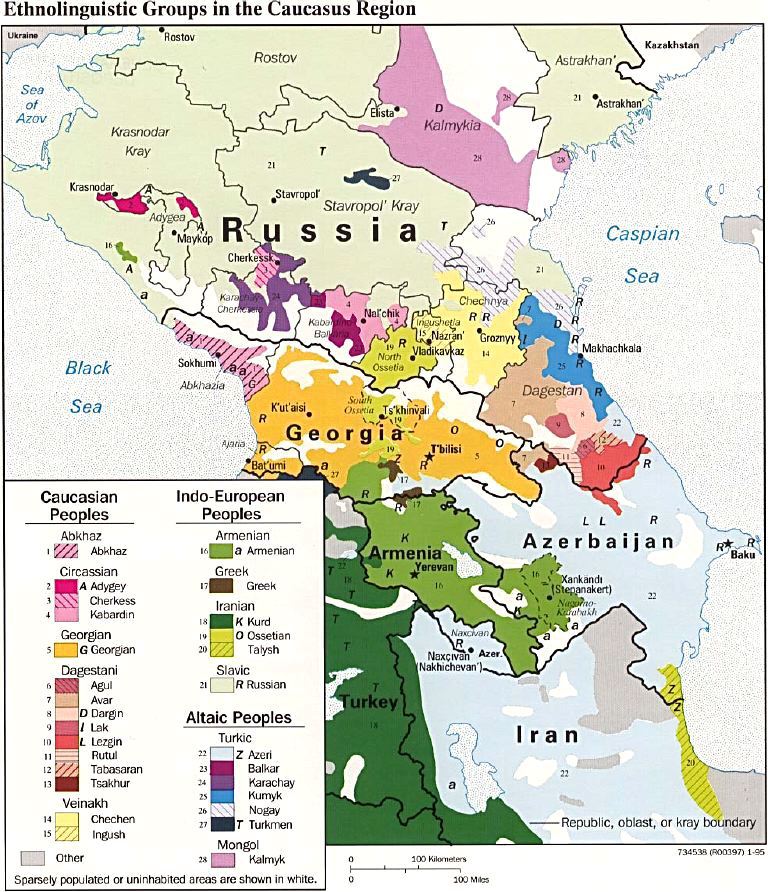

The Circassians (self-designation Adyghe) are the oldest indigenous people of North Caucasus. They were displaced in the course of the Russian conquest of the North Caucasus after the Russian–Caucasian War of 1763-1864. The main language is that of Circassian, a Northwest Caucasian language with numerous dialects; the primary ones being Adyghe (West Circassian) and Kabardian (East Circassian). The Circassians also speak Turkish and Arabic in large numbers, having been exiled by Russia to lands of the Ottoman Empire, where the majority of them today live. There remain roughly 700,000 Circassians in historical Circassia (the Republics of Adygea, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, and the Southern half of Krasnodar Krai), as well as a number in the Russian Federation outside these republics. The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) estimates that there are as many as 3.7 million “ethnic Circassians” in the diaspora outside the Circassian republics (meaning that only one in seven “ethnic Circassians” live in the homeland), of whom about 2 million live in Turkey, 700,000 in the Russian Federation, 150,000 in the Levant and Mesopotamia, and approximately 50,000 in Europe and the United States.

SP – Is the Biblical story about Babylon based on real events? Does this account contain elements of chronicle?

JC – No, it is not based upon any known real events, though it preserves a memory of the Ziggurats of Ancient Mesopotamia. The model for language diversification that it presents is backwards. We scatter and then our languages diverge.

What does “parent language” mean? Can the parent language be similar to any modern languages?

A parent language is just that, a language that has offspring. Usually ‘mother’ and ‘daughters’ are the terms used. Latin is the parent language of the Romance languages, Italian, Romanian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and a few other minor dialects. Latin still exists as a liturgical language. Usually the parent language has vanished, changed into its daughters. It will be like a real language, and similar to its offspring.

In one of your interviews, you mentioned the common language for all Indo-European people as “the language of ancestors of Circassian people”. What kind of language is it? Can you elaborate more about your scientific discovery?

I have argued in two papers that the Indo-European family of languages and the Northwest Caucasian one, the family to which Circassian, Abkhaz-Abaza, and Ubykh belong, shared a common parent language. I called this language ‘Pontic,’ after the region where I think it might have been spoken, the shores of the eastern Black Sea, Pontus Euxinus in Ancient Greek. Archaeological evidence, the kurgan burials, and some recent genetic evidence suggest as well that the Indo-European parent, Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Northwest Caucasian shared the eastern and northern shores around the Back Sea at a remote period, perhaps 5,000 to 9,000 years ago. Linguists often call such remote links phyletic ones rather than family ones.

It is important to understand that Circassian and its parent language, Proto-Northwest Caucasian, are not Indo-European languages, any more than any of the Indo-European languages or Proto-Indo-European itself are Northwest Caucasian languages. Their links go back much further than the time of either Proto-Indo-European or Proto-Northwest Caucasian as living languages, which I would place at about 5,000 years ago for each. An analogy would be with English and Italian. English is not a Romance language nor is Italian a Germanic one, but both languages are related because at a remote time both can be traced back to Proto-Indo-European.

Let me give just two concrete examples of related words, “cognates,” from the two families,

a. Proto-Northwest-Caucasian */a-r©a/ the-people, Circassian /ade©e/, Ubykh, /a-de©a/ the-Circassians, Ubykhs, Abaza /-r\a/ people, tribe, Abkhaz /-raa/.

Proto-Indo-European *aryo-, Indo-Iranian *Aryan, (found in modern Indic languages), Farsi Iran, Hittite arawa ‘free person’, Runic Germanic arjostiR, Greek aristos, etc.

Pontic *a-r-©o-. the-person-collective/abstract

b. PNWC */pNa/ ‘lightning strike’, /-Xwa-/ (/X/ is a palatal fricative) -fall.down. Ubykh /fa/ ‘to ignite by a lightning bolt, for lightning to come down’, Circassian, /pNe-LeLe-/ down-dangle, and /-f-/ or /-XW-/ ‘to fall, drive out, down’

PIE *paxwer ‘sacred fire’ (nominative case), *paxweni (dative case, “in the fire”), Hittite pahhur, pahhweni, pahhenes, Greek pu:r, English fire.

Pontic */pa-Xwa-r/, lightning.strike.fall.down-absolutive.case, */pa-Xwa-m-y/ lightning.strike.fall.down-oblique.case-into

Many linguists today are in search of the parent language (Homo Sapiens). From your point of view, what impact could occur, affecting humankind, if the parent language is found? Are there any discoveries that can become Pandora’s Box?

I take by this that you mean “Mother Tongue,” the original language from which all have descended. This is an old idea going back to an Italian linguist of the 19th century. If you do historical linguistics, you find that it grows harder to find cognates among related languages the further back in time you search. At some point it is not possible to distinguish between cognates and chance similarities, which today are fairly easy to find between any two languages, for example Russian ruka, and Mayan roka both meaning ‘arm.’ So, those of us who work on languages that go back to a parent that is, let us say, 10,000 years old, do not think that we can find anything tangible about a Mother Tongue that is perhaps ten times older.

Also, the 15,000 year time difference between the New and Old Worlds is now the boundary for distinguishing between cognates and chance similarities. That is why links between Old World and New World languages have not been found, with the exception of the recently uncovered ties between Yeniseian (Ket), and Na-Dene (New World) put forward recently by Edward Vajda.

Now people who seek the Mother Tongue, in particular Russian linguists, point to similarities among certain common words which we know as “core vocabulary.” Core vocabulary also uses a limited “core” number of sounds or phonemes, in scientific language.. For example, the word for ‘tooth’ usually starts with a /t/ or /d/ in very many languages. Now the PIE word for ‘tooth’, Latin dentum, Greek odontos has to be ruled out because it is actually based on the word ‘to eat, *Eed-, *Eod-, *Ed-, and is ‘the eater.’ Still there remains a residue of such words for ‘tooth’ in other families. What then are the Mother Tongue people seeing if these are not actual cognates as historical linguists understand them? One guess is that they are looking at the evolutionary remains of human language in the sense that they are seeing chance similarities among a limited number of core words that use a limited inventory of core phonemes. What is important is that their work reveals the core vocabulary to be an ancient relic of an earlier form of human language.

Finally a study appearing two years ago in ‘Science’ by Quentin Atkinson and others argues that the most complex sound systems are the click languages (Khoisan) of South Africa and that sound systems grow simpler as languages move away from Africa, mimicking the patterns found in human genetics. Most linguists think this cannot be right for two reasons. First very elaborate systems are found far from Africa. The databases used by the investigators are not very good at capturing such detail. Second, we have strong suspicions, I might even say convictions, that much of what we see in today’s languages is of recent origin. So, Caucasian languages were much simpler 10,000 years ago, while Polynesian ones were much more complex.

Unless we find a relic human or pre-human hiding somewhere and try to talk with him or her, we will never know the Mother Tongue in any direct way. Features of modern language, especially the patterns that all children show as they acquire their languages, offer strong clues as to how human language emerged.

When did you begin to learn the Adyghe language? What motivated you to learn this language? Was it difficult to learn the Ubykh dialect?

I began to look at Circassian in 1971. I first became interested in linguistics in 1967. I had studied Ancient Greek and Armenian. When I entered Harvard in 1968 I studied Farsi and Old Georgian. I also worked with a Digoron Ossetian, Aleksander Zouraeff, of New Jersey, who in his youth had been a friend of Trotsky. I saw the Daghestanis dancing in Kornilov’s Wild Legion in Eisenstein’s Potemkin, which caught my attention. In 1971, professor at Harvard University, Calvert Watkins, handed me a cassette of Abaza made by the late W. (William) Sidney Allen (1918-2004) of Cambridge, UK, and asked me to do a phonetic study of it. I then contacted Hans Vogt of Oslo, who generously sent me his recordings of Ubykh. I studied Ubykh that way and had only a little trouble with its sounds. I worked with two speakers of Bzhedukh, who lived in New Jersey as well, Rashid Dahabsu and Hisa Tarquakho. Bzhedukh was amazing and was a challenge even for me with my”good ear,” as they say of some one who is good at phonetics.

So, Bzhedukh is the most difficult, followed by Ubykh, and then Abaza. My Abkhaz is least good. Kabardian is easiest, but stylistically most elaborate.

These are all amazing languages, important for the theorist of linguistics as well as the historian.

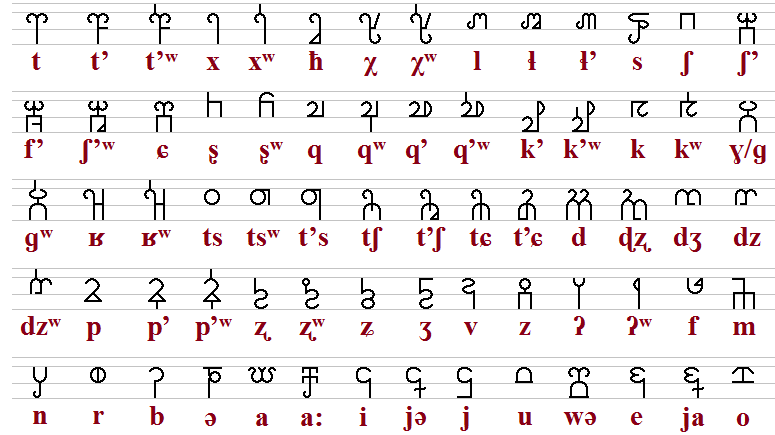

The Adyghe Alphabet

Hittite language manuscripts are related to the 13-18th centuries B.C. Manuscripts of Luvian cuneiform and the Palaic language refer to the 13th and 14th centuries B.C. Luvian hieroglyphic texts are related to the 16 century B.C., but many scientists credit a great bulk of these texts to the 8-10th centuries B.C. Does fluency in the Adyghe language make it possible to read and translate Hetto-Luvian manuscripts of the Indo-European language group?

No, this is not true. Hittite, Luvian, Palaic, and the later Anatolian languages, such as Lycian, Lydian, and Carian, form a branch of Indo-European, albeit a branch that left from the main body first. Slava Chirikba has argued in his Moscow doctoral thesis that Hattic, a liturgical language found within Hittite religious texts and not an Indo-European language, can be understood in terms of Abkhaz and Circassian.

The problem here is the names. ‘Hittite’ comes from Hebrew and is a distortion of the non-Indo-European ‘Hatti.’ The Hittites, Indo-European, called themselves ‘Nesili,’ but no one refers to them by that name.

Am I correct in understanding that the Hatti are ancestors of Circassians and are not Indo-European people who lived in the territory of Ancient Anatolia? The Nesili conquered the Hatti. After that the two nations merged, their languages also. The ancient Hebrews named this mixed nation the “Hittites”, so the Hittites is a mix of Indo-Europeans “Nesili” and Non-Indo-Europeans “Hatti”?

Yes. First, the Hatti were related to the Circassians, but were closer to the Abkhaz. This makes sense because the Abkhaz were nearer to them geographically than were the Circassians. Second, once absorbed, the Hatti lost their identity and went into making up the Nesili, whom we call Hittites.

The Hatti people were cousins to the ancient Adyghe people, not their direct ancestors. If we accept the link between Hattic and Abkhazian, which Slava Chirikba has shown that we should, then we must accept a link between Hattic and Adyghean.

Why have western scientists drawn a conclusion that there is no correlation between the Iberijsko-Caucasian and Indo-European languages?

If you mean by Iberijsko-Caucasian the link between Basque and South Caucasian (Kartvelian) or the other two Caucasian families, then it is because we cannot find a decent number of cognates between Basque and Caucasian groups. We find only a few vague similarities. So, we don’t speak of Ibero-Caucasian. As to Indo-European and Caucasian, there is really only my work. Heinz Faehnrich of Jena, Germany and Professor Klimov of Moscow tried to compare some Indo-European words to Georgian or Proto-Kartvelian, the parent of Georgian, but again there are only vague similarities.

Is it correct therefore that the Iberijsko-Caucasian language family and Adyghe-Abhazian language group can’t be related to Indo-European languages because there are few convincing works on this subject? How can linguists prove a language belonging to this or that language group? Is it important for scientists to do a linguistic research on this topic?

I think I have shown that there is a strong case for a distant genetic relationship between Indo-European and the Northwest (Adyghe-Abhazian) language family. The link between Northwest Caucasian and Northeast Caucasian (Daghestani) is probably equally distant. Northeast Caucasian is characterized by grammatical gender prefixes for masculine, feminine, countable, non-countable, etc. Such prefixes are called “classifiers.” These are only relics within Northwest Caucasian and seem to be absent altogether from Indo-European.

Recently it has been claimed by Ilija Çasule that the Burushaski language, an isolate language (without family link) spoken in Gilgit and Hunza, is in fact related to Indo-European. Burushaski has grammatical class markers, just as does the Northeast Caucasian family. I would interpret this picture this way: at a remote time, perhaps 7,000 years ago or more, there was a large language family centered on the Caucasus. In the north west it contained Indo-European, south of that Northwest Caucasian extending down into present day Turkey as Hattic; in the south east it contained Northeast Caucasian, and to the east of both Indo-European and Northeast Caucasian it contained the ancestor of Burushaski. There are a few words in Indo-European that have “unstable” initial consonants, such as the word for ‘door’, that in Tocharian comes out simply as ‘or’, or the pair in Latin of lacrima (< Old Latin dacrima) and acridus, cognate with English tear (of the eye). These may be traces of very ancient grammatical classifiers within Indo-European.

Historical linguists tend by nature to be very cautious. Proving these wider relationships would require substantial extra work in terms of learning languages, so we are just beginning to explore such links.

Is it possible to analyse and make conclusions about the nature of an ethnic group based upon language structure without examining other phenomenon which Wilhelm von Humboldt named the “spirit of language”? For example, Modern Cultural Linguistics defines a special term for this phenomenon: “Pragmatical or Cultural Utilities”. What is your attitude to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis?

I think that language does shape our thoughts and view of the world in complex and subtle ways. As Roman Jakobson said, “Language tells us what we must say. It does not tell us what we can say.” For each language I have studied, the world feels different for a variety of reasons: the actual ideas in the vocabulary, the order of information and what I must anticipate as I work through a sentence, the sorts of information that I must be aware of so that I can meet the demands of the language, the emotional images and metaphors peculiar to that tongue. The Sapir-Whorf-Humboldt hypothesis is correct therefore in some broad sense. There are some glaring exceptions, however. For example, there is no gender in Farsi or Japanese, and yet these cultures traditionally rank women very lowly.

In both the Adyghe and English languages, the word “you” has the same form for the 2nd person singular and the 2nd person plural (you=you). When addressing seniors and superiors, the English and Circassian languages use the same pronoun “you”. This correlation emphasizes a “close” or “informal” attitude of relationships between young and old people, as well as acquainted and unacquainted. Simultaneously, Pragmatical Utilities of Adyghe people denotes absolute respect for seniors. English speaking people portray a so-called “easy” relationship between unacquainted people with a familiarity in dialogue (you=you) that is considered to be polite. Besides “you”, there are other forms in English for expressing politeness to seniors and strangers, especially by means of modal verbs. What do you think about the nature of language lacunas?

The English familiar ‘thou’ is no longer used, but has been replaced by the formal ‘you’. In Adyghey /we-/ is for single or familiar, and /s!We-/for plural or formal. Some languages, such as German, use third person plural for formal ‘you’, German Sie. Languages show a range of such pragmatic distinctions, some of which seem very odd or counter intuitive. If there is a lacuna, then the language will find a way to be polite or intimate/familiar in some other way. This is an example of how the Sapir-Whorf-Humboldt hypothesis does not work.

Is it possible that the lexical lacunas are compensated by Pragmatical or Cultural Utilities or other lexical means? Perhaps both Adyghe and English peoples don’t need to add another lexical unit for denoting the concept of politeness because the whole ethnic group knows how to act without additional words?

Sometimes the culture clearly dictates how we are to act without the language having any overt role, but usually, the language will reflect the culture in some way.

Can “briefness” be a feature of a language behavior of the whole ethnic group?

Yes.

Considering that “incompleteness” or so called ‘innuendo” in the dialogue of Circassian people played and plays an important role, can it be so that in the Adyghe language, Pragmatical Utilities are the first, language is the second?

Pragmatics tells us how to use our language. The two dimensions are just that: they are independent aspects of language.

From your point of view can this “innuendo” and “briefness” be connected with the absence of written language?

I do not think so. Hungarian had strict rules for use, but was written.

How do you explain the existence of nations that had no written language?

Not having writing is the natural state of language. Devising a system of writing comes with much urbanisation and development. There are several ways of writing: logographic, syllabic, and alphabetic. Logographic writing, like that of Chinese or Ancient Egyptian, is natural in that each symbol stands for a mental unit, a concept. Syllabic writing is also natural because each symbol, standing for a consonant and vowel, corresponds for a perceptual unit of speech, the syllable. It is the alphabetic way of writing that is a little mysterious because our nervous system responses are not fast enough to scan the incoming consonants and vowels separately; some sort of parallel processing must be involved.

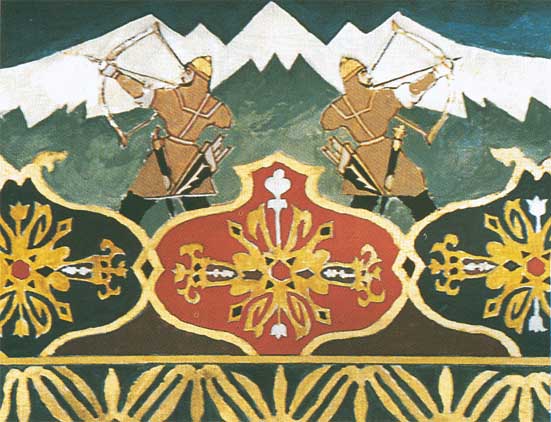

The Circassian Flag

Adyghe people are creative, their arts and crafts very developed even nowadays, yet there was no written language. How can it be that during centuries no one representative of the ethnos who had linguo-creational thinking made any attempt to write such a masterpiece of oral national creativity as Nart Epos? Why are there in Nart Epos many mythical plots of Hatti, who had transmitted these plots to Circassians, but they haven’t transmitted a written language to Circassians?

I think the ancestors of the Circassians, Ubykhs, and Abkhazians, may well have had older systems of writing, but were lost because the ancestors were involved in too many wars. They may also have had writing systems based on other ancient languages, such as Greek, and Ancient Persian, etc. Recently I collaborated with a Classicist, Adrienne Mayor, and an art historian (David Saunders) on deciphering “nonsense” inscriptions on some Ancient Greek vases. These turned out in many cases to be names or phrases in ancient forms of Circassian, Ubykh, Abkhazian, Georgian, and Ossetic or a related language. So, I think these oldest attested forms of these languages (more than 2,500 years old) may represent the ancient forms for writing using Greek script.

Some modern admirers of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis consider the absence of the feminine gender in the Adyghe language as an indication of a contemptuous relationship between men and women in the whole ethnic group. But Adyghe Pragmatical Utilities prescribe men as having inherent respect toward women. In the Abkhazian language, there is a category of gender. Was there such a category of in the Ubih language? How can you explain this contradiction? Did you note this contradiction in your translation of the Nart Sagas? There are some cultural and language distinctions between ancient England and ancient Circassia, but you’ve used the lexeme “Lady” for the Adyghe lexeme “Guashche” in your translation; Why?

Respect for women is a central principle in all Northwest Caucasian peoples, whether their language has gender or not. Note that in my answer to an earlier question I cite Farsi and Japanese as languages where the role of women is not reflected by gender distinctions in the language.

The Ubykh gender word was an archaic pronoun /xWeGHWa/ used only for female slaves.

/gWashe/ was translated as ‘lady’ by my teachers.

When the genders, masculine, feminine, and sometimes neuter, are semantically extended to non-living objects, it is not clear how much of the original gender sense is preserved. Note German, der Gabel, die Loefel, das Messer, masculine, feminine, and neuter dinnerware.

But if Ubih people had a special gender word /xWeGHWa/ used only for female slaves, can it signify that they treat female slaves rather humanely?

My guess is ‘yes’. They were polite to them. I would think the word had a sense like ‘woman.’

What difficulties did you face during translation of the Nart Sagas?

I tried to strike a balance between fluent English and preserving the tone of the originals. I was not always successful.

What century would you date the genesis of the Nart Sagas?

They are layered, some being very old, perhaps 2 or 3 thousand years old, and some only a few hundred years old.

In your comments to translation of the Nart sagas, you have shown the place of Adyghe myths and legends in the system of world mythology. You also connected mythological plots of the Nart sagas to mythological stories belonging to other nations of the world, thus deciphering many places in the epos that are not clear to the modern Adyghe recipient. Do you think the Narts actually occupied the Northwest Caucasus B.C.?

I think the Nart sagas reflect the lore of a civilization that arose in the North Caucasus and spread out across the steppes.

Do you imply the theory that asserts Indo-European civilization had arisen in the North Caucasus? Can the Narts be the prototype of those first Indo-European people which have spread worldwide?

They certainly continue some very ancient features that probably extend all the way back to the era of Indo-European unity and perhaps back to that of “Pontic,” when Indo-European and Northwest Caucasian were one. But, it is hard to prove this.

In your commentary relating to the Nart sagas, you draw interesting parallels of plots of the epos to ancient Hittites and also ancient Greeks. How do these plots appear in Nart sagas? Is it true that the Ancient Greeks borrowed some plots from Nart epos? What kind of plots did they borrow? Are there any plots which are universal and easily recognized today by the world community?

There are parallels with myths from the Slavic, Indo-Iranian, and Germanic worlds as well, even a few with the Celtic.

The Greeks borrowed chiefly the Prometheus myth and the Cyclops.

I think the most widely recognized themes are the winning of a princess (Psatine), the adoption of a lowly foreign woman by the older leader (Warzemeg and Setenaya), the fertile queen (Setenaya), the bringing of fire, the slaying of demons, the incorruptible hero (She Bartinuquo, Pataraz) and the trickster (Sosruquo).

Each epos can have answers to many questions on the character and destiny of the ethnic group that created it. From your point of view, why have the ancestors of Circassian people chosen the slogan “If our life has to be short, let our glory be long”, as it was known before the time of Christ?

Because you and your ancestors before you were a warrior people whose chances of dying in battle at a young age were high.

From your point of view, is it possible for modern Circassian people to change this program?

Yes, I would expect that to be possible. Culture is adaptable, functional. The era of constant warfare and widespread death is, I hope in the past. The Circassian and Abkhazian people are intelligent and hard working. There is no reason why they cannot become prominent members of the modern world.

Within an ethnic group, can the development of language itself be connected with educational and spiritual development?

Language is probably the most important dimension of ethnic identity. If education and spiritual development are to succeed as part of the heritage of your people, then they must keep their language(s) alive.

Before the Second World War, Italy did not have a national literary language, people in the South not always fully understanding people from the northern part of the country. Mussolini engaged the efforts of the best Italian linguists to establish one literary language that was accepted by all regions of the nation. Today, in Adyghe, there are numerous disputes concerning the literary language. From your point of view, is it possible to create one language model that would be common for all Adyghe people today?

It would be easiest to have two: Kabardian and some Adyghey dialect, either Shapsegh or Bzhedukh. But if one language is desired, as with Italian (though there is a growing movement to have Neapolitan literature in the local dialect), then perhaps the most complex language would be the one to adopt. That would be Shapsegh or Bzhedukh. This sounds counter intuitive, but it would work this way. The c?mplex dialect makes distinctions for the most words and forms; someone who speaks it need not guess at what is being said or written. For a simpler dialect, say Kabardian as opposed to bzhedukh, the speaker would simply ignore all the contrasts, seeing them as odd orthographic forms, and use his or her own dialect. Something very much like this is going on in many of the European languages from Russian to English. So, in English most people ignore the <w-> in write or the <wh-> in what, etc., and just say these words as [rayt] and [wat]. So it would be with a «Universal Adyghe.»

So is it correct to say that today a difference between the Kabardian and the Bzhedugh dialects of Adyghe language is approximately the same as the difference between a Classical English and American variant of English language?

I would say they are like Portuguese and Spanish or perhaps like Dutch and German, but maybe not so much. By contrast Circassian, Ubykh and Abkhaz – Abaza are like branches of Indo-European: Germanic, Latin, and Sanskrit, say.

Many language groups of the world have different tribes or subgroups speaking a variety of dialects within the larger group. There are many dialects in France, for example, the Lotharingian dialect, Breton, and so on. But at the same time, when we speak about the language that is common, the “French language” for all French speaking people, nobody tells each dialect group that the rule is to speak the “French language”. In England, there are also varied regions of people who speak different dialects of English. Again, when the conversation leads to a common word, there is no stated instruction to speak the “English language”. In Italy no one states, speak the “Italian language”. Conversely, it is normal to tell Adyghe people with varied dialects to speak the “Adyghe language”. Today, there are twelve tribes of Adyghe people with each subgroup speaking its own dialect. This complexity sometimes reaches absurdity when a linguist tries to formulate the name for a dissertation. Many authors must write: “The linguistic research is executed on a material of Russian, English, French, Italian, and Adyghe languages”. From your point of view, is the term “Adyghe languages” convenient for usage?

They are dialects that share a wide range of grammatical features. The variation from Shapsegh to Kabardian is great. Besleney, however, is halfway between the two. There is therefore no clear place to draw a dividing line.

Also, all Shapseghs, Bzhedukhs, Chemgwis, Abdzakhs, Hatuqoys, Besleneys, Kabardians, even the Ubykh, all call themselves Adyghé. They can all understand each other, although sometimes a bit of practice is necessary.

So, they all feel themselves to be ‘one people’, even though in a local sense they also feel distinct. I would say that there is an Adyghé (Circassian) language with many dialects and also Ubykh. It is a case of one ethnic group with two languages, one of which, Ubykh, is almost extinct.

The Abkhaz and Abaza feel themselves to be related to Adyghe, though however distinct.

Let us compare this with Italian. In Italy the word for ‘wine’ runs from the Sicilian ‘vinu’ up to the Roman ‘vino’ with an initial glottal stop and with the vowel nasalized just as in the French vin. Just northeast of this dialect spectrum, as it is called, is Friulian/Romansch, which the speakers all call Furlan. This language is not intelligible to Italians of any sort of dialect, nor can Furlan speakers understand Italians. The Furlan must learn Italian in schools. I know this from working with a woman who spoke Furlan, and from the large number of Italian speakers of all sorts of dialects that live here in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Adyghe languages are a fruitful subject for scientific research because the people are scattered worldwide, the material of Adyghe languages retraceable to the process of language interference. The greatest Adyghe diaspora is in Turkey. Not so long ago, Adyghe people in Turkey demonstrated on city streets petitioning the government to help save their native language. Do you think it would be effective to create study centres of the Adyghe language in countries where Adyghe communities are located?

Yes, such centres should be established if these countries wish to be seen as democratic and pluralistic. In the case of the Adyghey the countries need not fear secessionist movements. Adygheys are generally loyal citizens of whatever country they live in.

What researches based on the material of Adyghe languages are carried out in Canada?

There are only two scholars in Canada who work on Adyghey: myself and Kevin Tuite at the Université de Montréal. We both work on a variety of grammatical puzzles that the Adyghe language presents.

What kind of researches are they? Can you possibly give us more information?

Professor Tuite works on ancient Svan, Khevsur, and Chechen rituals and their pagan gods. I work on the complexities of the Circassian and Abkhazian verb and how they are perceived as units of speech. I also study the syntax of these languages, working on their histories, in addition to those of the Pontic language.

Both Canada and Russia are multinational states. What kind of language policy exists in Canada? Are there any problems connected with bilingualism or multilingualism, and what does the government do for preservation and development of the aboriginal language?

Canada has English and French as official languages. This policy is deeply flawed because it demands that all people speak both languages. Languages do not work this way, because they are local phenomena. This demand is actually enforced for anyone working in government. This demand serves to alienate those people from the English speaking West who want to pursue careers in government.

As to aboriginal languages, these can be used for voting. Many regions have centres where aboriginals can receive up to two or more years of university training in their languages. Efforts centre around dictionaries and basic grammars for primary grades, some native groups seeming more interested in preserving their language than others.

Today people use English to find the common language, but having won the world language map, English has greatly changed in many countries, thus losing its classical shape. What transformations have occurred to the English language in Canada?

English in Canada does not differ significantly from that in the U.S. Some people in the Maritime Provinces have a very heavy accent that few outside this region can understand. For ‘boy’ they say [bay]; for ‘buy’ they say [booy].

Do the people of Canada have any views about regions of Russia or of the North Caucasus, and are those views positive or negative?

As a circumpolar nation Canada feels a certain affinity for Russia. Very few know of the North Caucasus. We have Old Believers out in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and some people know that these were in the Caucasus before they came to Canada.

Is it normal to use the aesthetics and mythology of the regions in creating positive images of the whole country?

Yes, of course. Mythology is the wine cellar of the human spirit. One naturally turns to its images and themes to capture the spirit and past of a people.

In Nart epos, are there the images and characters which could adequately represent the basic concept of sports events on an international level? Do the images of old Circassian Narts correspond to the spirit of modern Olympic athletes?

The Narts were powerful and fearless warriors when they were at their best. A Nart theme for Sochi Olympics is a great idea!

From your point of view, will it be interesting to the world community to see characters of Nart sagas in the Olympic Games as well as other images characterizing modern Russia?

I have a friend who is a prominent, retired physicist from Oxford. In exchange for a book he has sent to me, I have sent him a copy of my Nart sagas, and is most impressed. This is what he said: “The stories speak with a fascinating voice, quite new to me.” I therefore think the Narts will have great appeal for people beyond Russia and the Caucasus. Keep in mind that The Ossetians, Ingush, Chechens, and Svan also have Nart tales. They are part of the heritage of the entire North Caucasus. Each people has its own unique version. I have a volume of Ossetian tales that I hope to publish this summer also.

In 2014, Russia will host the Olympic Games in Sochi. You are a famous expert mythologist. What would you advise to public relations agencies that will create the image of Russia in the forthcoming Olympic Games?

It would be both realistic and moral to portray Russia as the multi-ethnic society she is. All modern states are pluralistic, though one ethnic group has dictated the nature of the predominate civic culture. Such a unified civic culture does not preclude local ethnic ones as well or in any way deny a population in a city its diverse backgrounds.

Some acknowledgement of the Circassian and Ubykh heritage of the Sochi region would be both honest and politically wise.

John Colarusso, Ph.D. (Harvard)

Born in California, raised in Mississippi and New Jersey, John Colarusso first studied physics and then took two degrees in philosophy (BA Cornell, MA Northwestern). He earned his doctorate in linguistics from Harvard University in 1975. Since 1967 he has studied the Caucasus, its languages, myths, and cultures.

He has taught at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario since 1976. Since 1992 he has been active in advising leaders and policy makers in Washington, Ottawa, Moscow, and the Caucasus itself.

In addition to more than sixty-five articles on linguistics, myth, politics, and the Caucasus, he has written three books, edited one, and is finishing two more.

Saida R. Panesh was born in the South of Russia, North Caucasus, Republic Adyghea. She graduated from Adygh State University (Mykop), Department of Foreign Languages then took a Postgraduate study and defended the Candidate’s Dissertation in Linguistics at Kuban State University (Krasnodar). She is now an Associate Professor at Department of Romanic and Germanic Philology at Kuban State University. For the past fifteen years Saida has also worked as a journalist for numerous publications, author of works on a number of subjects including Business, Economy, Culture, Sports and Science.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!