By

Gulcin Newby Kennett

Contrary to popular belief, despite its recognition in the early 1960s, African-American theater did not begin then, but centuries before.

It is believed that the slaves began performing for their white owners even before the ships arrived in the shores of America. The plays they performed used rituals and hidden satire. Satire was an important part of African culture and disputes were often aired through tongue-in-cheek performance in order to avoid violent confrontations. If we look at the earliest beginnings of drama in the form of the spiritual magical rites of the Egyptian priests of Isis / Osiris, we can safely say that the evolution of such extravagant theatrics kept close pace with the evolution of humanity. Moreover, since modern anthropology can now trace the evolution back to Africa, we can conclude that Africa may have been the source of all theater. Back on the slave ships, the use of satire worked as a double-edge sword, which although seemingly mocked their own blackness, actually ridiculed their owners who took pleasure in watching these performances.

In the American slave community, on certain occasions such as deaths or freely adapted Christian holidays, dramatizations in the form of improvisations, which required audience participation, were held. These performances made frequent use of sarcasm and humor, and were almost always accompanied by music, dance and mime. A wide range of elements from free adaptations of Biblical stories to magical bush culture composed the core of this tradition.

Another type of theater involved the dramatization of the gospels, in which African-Americans offered their own interpretation of Creation. These dramatizations borrowed from the Old Testament and African folklore, and in such dramatizations, the main character was often the devil, who represented Anansi (spider of the Caribbean), Eshu of Brazil and Legba of Haitian Vodun.

This interactive form of play was later echoed in the Alternative Theater Movement of the 1960s by the middle class white youth who reacted to the middle class values of their parents’ society. The most extreme of the Living Theater’s pieces was Paradise Now. It began with actors circulating among the spectators denouncing strictures on freedom (to smoke marijuana, travel without a passport, to go nude in public and the like). Thereafter, both spectators and actors roamed the auditorium and stage indiscriminately, many removing their clothing and some smoking marijuana. Actors provoked some spectators into voicing their opposition and then overrode them, often by shouting obscenities or even spitting on them; at the end the company sought to move the audience into the streets to continue the revolution that began in the theater.

In contrast, the black audience of the improvised interactive theater did not take their emotions into the streets. Instead, they embraced theater as a way of discharging from the laborious yet, unrewarding life of a slave. That is, they took refuge and found catharsis in its magical comical world.

Sure enough the whites discovered this form of entertainment among the blacks, and the seeds of a tradition which came to be known as the so-called Negro Plays, which were about Negroes although written by whites to be viewed by an all-white audience. Otherwise known as minstrel shows, these performances caused the glittery rich whites to flock to the white owned and operated “Negro theaters” in Harlem. In these plays, black performers painted their faces even to a darker shade and wore white gloves to underline the contrast. This tradition continued well into the mid-fifties. By then the black performers had already been replaced by white actors who painted their faces black and acted silly while on stage.

Around this time, an organization known as Federal Theater Project was trying to fight discrimination against blacks in theater and protect the rights of the black actors hired to act in these plays. They opposed the use of black face by the white actors and any kind of stereotyping of other cultures. Unfortunately, when the House of un-American Activities Committee decided that any campaigning for racial equality was communistic propaganda, Federal Theater Project had to close its doors. However, the seeds of political awareness had already been dropped into African theater.

During the McCarthy era, any expression of blackness was considered to be subversive, un-American and communistic. There were many black actors who were left unemployed since, during this period, many whites who frequented Harlem theaters stopped coming for fear of being branded “a communist”, thus eliminating the demand for such a form of entertainment. These actors played an important role in developing black community groups in which plays were written, performed and viewed by an all black audience. These groups gave rise to the foundation of the Harlem Suitcase Theater by Langston Hughes and other companies such as the Rose McClendon Players, The American Negro Theater and the Negro Playwrights Company.

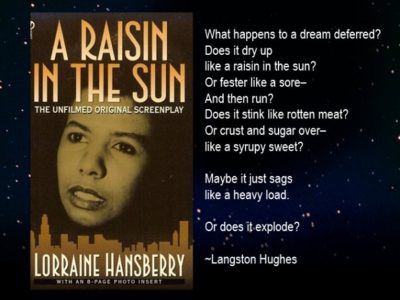

In the late fifties, a turning point was reached when ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ by Lorraine Hansberry won worldwide critical acclaim and made it to Broadway amidst endless controversy. This was particularly significant because until that time no black writer, black actor, black director, or technician had benefited from theater financially.

The play is based on a Langston Hughes poem ‘Harlem’ and effectively showed how the dream of integration was constantly thwarted. Some criticized Hansberry for not questioning within her play the situation of blacks although she had said that her play was not a black play but a play about an American family in a conflict with a corrupt society.

Following the riots in Watts and Harlem, government sought to neutralize black anger by giving it a chance to express itself in the medium of the theater. This way, they hoped to control its rage by using the classical principle of the theater as a means of purging masses of their destructive appetite, and therefore maintaining law and order in the society. It perhaps worked, but it also helped the development of a generation of fresh revolutionary black playwrights in the 1960s. Among these were LeRoi Jones, Douglas Turner Ward, Lonne Elder and Archie Shepp.

LeRoi Jones’ ‘Dutchman’ won the Obie prize for Best Drama of the 1963-64 seasons, and Jones was hailed by the New York theater critics as an important voice. The play has two characters; a middle aged white Bohemian woman and a young middle-class black man in a train compartment setting. The woman makes sexual advances towards the black man, and when he does not join her in her wild dance, she starts to insult his race and his bourgeois ideals. “Dutchman represents a stylistic duel, simultaneously sexual, racial, and metaphorical, which is enacted both physically and verbally.”

Dutchman created many arguments between the critics and stirred much controversy among the audience. In some States, police attempted to prevent its production and newspapers declined to advertise it. “Although there have been many revivals of the play in college and community theaters throughout the United States, Dutchman is rarely seen on commercial stages.” This fact alone should be considered a solid testimony to the real strength of the ideas and feelings contained within the play.

After converting to Islam, LeRoi Jones changed his name to Imamu Baraka (and later became known as simply Amiri Baraka) and founded the Black Arts Repertory Theater (BART) which rejected all Western theatrical conventions and concentrated mainly on African mythology, ritual, African-American history. Once again, arts completed a full circle and the fine line between art and life disappeared. Therefore, it would not be an exaggeration to claim that imitations alter reality.

African-American theater has always been a playground for a search for one’s cultural identity or an effort to proclaim cultural identity in a world so alien yet so familiar. The richness of an oral tradition which has been carried through generations of slaves bound by fate shows through the improvisation of the performers. (Slaves were forbidden to read and write; therefore, African-American culture was traditionally highly developed in terms of oral, aural and improvisational skills).

Music plays an important part in the expression of the act and the rhythms of speech set the mood for the audience, participating in the call and response manner. This rhythm is achieved through the use of alliteration and repetition. According to African-American dramaturg Geneviève Fabre, “through music, black people affirm their ability to control chaos, to confer meaning on absurdity and to restore spirituality to the universe.”

All of these significant characteristics make African-American theater a very unique tradition which deserves more attention worldwide.

Sources:

* The Golden Bough, A study in Magic and Religion by Sir James George Frazer

* The Essential Theater by Oscar G. Brockett, sixt edition, 1992

* Forward to the Black Drama Anthology, Edited by Woodie King & Ron Miller

* Drama and performance, an Anthology, Edited by Gary Vena & Andrea Nouryeh, 1996

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!