By

Muhammad Nasrullah Khan

Every evening, I return from my office like a tedious idler. The street where I live hails me by a haze of smoke, heat, and noise. The scent of turmeric, wafting from open windows, curls around my nostrils and delicately flows inside my nose and dances downward to bring tingling to my lungs. Mothers call for their children as the light fades and dusk threatens to give way to darkness. A big black cat meandering through the mess with her five kittens rekindles my sense of direction. I stroll down the broken cobblestone street and turn right at the corner. A blind man sits there with his dirty old mat and a begging cup clasped in his wiry hands. Among all these things, a donkey always brings me to a pause.

I encounter the donkey as I turn at the last dark corner to my home. His master has left him, abandoned him to die. His graying mane falls into his eyes and flies swarm his ragged and dirty coat. His front legs wobble and falter as if they have both healed poorly after a grievous injury. I look into his eyes and can see years of hard labor. The donkey struggles along with a noble sense of purpose. He seems to know where he wants to go, but despite Herculean efforts, he manages only to proceed a few feet before falling. I watch, silently willing him on as he manages to regain an upright position, but then, he trembles and collapses into a heap once more.

This donkey reminds me of Ditha, a figure from my childhood. He was a man, a good man, but he led the life of a donkey. His face seemed carved from burnt stone with heavy wrinkles that made him appear older than he was. His big front teeth gave the impression of a perpetual smile. He had no family—no one to awaken a smile on his face, no one who shared the same blood in their veins. Only the animals were loyal to him.

I first learned that Ditha was a human when my father one day tested my learning about numbers and counting.

“Son, how many animals are in our courtyard?” he asked me one afternoon in early fall before the winter rain began.

Ten,” I replied with a triumphant smile.

“No. Try again,” he encouraged.

Eager to prove my prowess, I counted on my fingers to ensure none were missed.”Three goats, two cows, one buffalo, one horse, one donkey, one dog and one Ditha.”

“Oh, no, son. Ditha is not an animal. He is human, just like us.”

I balked. “How could that be? He lives above the barn—he is as filthy as a goat and he barely speaks.”

“Perhaps,” my father replied softly, “that is because people don’t bother to speak with him. What if we treated Ditha not as livestock, but as a person the same as you and me? Does he not feel pain and love, just as other people do?”

Ditha moved as the animals did — slow and lumbering around the yard, and only with purpose to get to food. He smelled as they did, and his hair was unkempt like theirs. He did not look anything like we do, yet my father told me he was a human.

I couldn’t sleep that night. My brain raced with questions. If he is a man, why does he live like animals? Why does he sleep in the barnyard? In my dreams I saw Ditha run like a horse and eat grass like a goat. I couldn’t help but feel pity for him.

Often, I wandered into the stables to listen while he murmured to the goats and sheep. Little did I know that they were his only friends.

Although he was always there I knew little about him –— only that his mother died when he was ten, and being a hooker’s son, he was driven out of town. My grandfather, then the village chief, brought him home and put him to work to earn his keep. Two meals a day and a room in the spacious shed was more security than anyone might have dreamed possible for someone in his station.

It was said that his mother gave him the name “Allah Ditha”, which means “Given by God”, but people soon left off the “Allah” and called him “Ditha”. He was forgotten by God as well.

We lived in a small village at the foothills of the hot, dry Black Mountains. Only one ancient well provided water for the town; all of the houses crowded around it. Everybody knew how precious it was. Ditha worked hard for us. Each morning he drew water from the village well. His strong arms brought up bucketful after bucketful without ever seeming to tire.

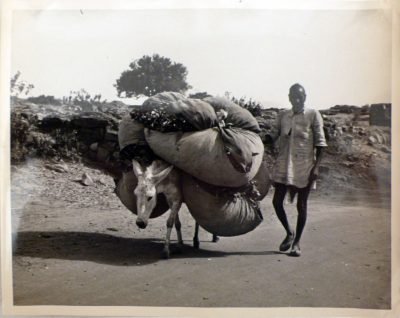

He would take the animals out to graze, patiently leading the slow, scattered herd to the pastureland beyond the houses. Ditha remained with them all day long, ever-watchful for predators and danger, caring for them as his own children. After returning them to their pens at the end of the day, he would reappear in the village, riding on the slow, old donkey, his weathered face and wind-whipped clothes hanging on his thin frame. As he rode through the streets, the young boys taunted him for their own wicked pleasure.

“Hey, Ditha,” someone would shout. “Your girlfriend, the ass, moves like you put her to better use today.”

“No, don’t say that!” someone else would shout. “The donkey is really Ditha’s sister! Can’t you see the resemblance?”

Their laughter echoed down the street. Once, some young guy, not yet fifteen, took a small stone and threw it at Ditha. Whether Ditha’s feelings were hurt by the ridicule of the villagers, he never said, and it took many years to cross my mind that it might have.

As I grew into a young boy, I began to watch Ditha a little more closely. Every evening he made his way down the Black Mountains with his sluggish animals following him like a tattered line of withdrawing troops. I began to wait for him, standing at the big front door of our courtyard. He would appear with his animals accompanied by the sounds of chimes reminiscent of tragic music in an old film.

Then came the stories — oh, what wonderful stories they were, featuring wolves, lions, and other fantastic creatures! He began to bring me gifts —wild fruits, beautiful flowers, and tasty mushrooms. The gifts were nice, but it was the stories for which I waited. He had a quiet, gentle way of making ideas come alive, and story-time quickly became a favorite part of my day.

He possessed a wit and sense of humor that could make anyone laugh. Thursdays and Fridays were Ditha’s favorite days. The more superstitious in our village made deliciously sweet dishes and left them among the grove of olive trees to appease the “ghosts.” Ditha would sneak into the grove and eat the food, causing the villagers to marvel that their offering had been accepted. Each week they’d attack the practice with renewed faith and vigor. Ditha’s eyes would twinkle, and I could hardly contain gales of laughter.

I soon came to know our Ditha as a man with a big, loyal heart and a smile, always at the ready. He never repaid malice or coarse joking with anything but kindness. Though he had no home of his own and his clothes were ragged and worn, he was full of gratitude for the little he had. My grandfather would have allowed Ditha to ride the sweet-tempered horse, and though he cherished him, he would only ride his little grey donkey. He told me once that he was born to ride his donkey, which seemed explanation enough. Ditha left a lasting impression on my childhood memories.

********

My cousins and I grew to be young men. Our grandparents died, and my eldest uncle became the head of the village, but Ditha remained the same. His responsibilities increased, for he carried even more jars of water on his frail shoulders. Uncle was very strict with Ditha and would often beat him with an aspen broom.

Despite his hardship, Ditha was quick to turn around his life. The most prominent change was in his clothes. Previously, his one set of garb went for months unwashed, then he started washing his clothes every week. This new fastidiousness did not go unobserved for long, nor did the motivation around it.

Soon, it emerged that Ditha had gotten into a relationship with the beggar-woman! Hers was a tenuous social position, a step below that of Ditha. The villagers fussed over the affair between Ditha and his outcast object of desire.

“The donkey-boy is in love?” They wondered and curled their mouths.

News of the sordid love affair soon reached my uncle. He shook his head and scoffed.

“Who can love such a donkey, someone who lives like an animal?”

Uncle could have beaten Ditha for his affair. Instead, he decided to humor the outraged sensibilities of the village aristocrats.

The issue was to be decided in a mock village assembly. One evening, all the so-called nobles flocked in my uncle’s big yard, drinking fresh camel-milk and telling raunchy jokes. Ditha sat on the ground in front of them, his head bowed. He appeared to ignore the snickers of the men. I crouched in the darkness and peeked around a corner, watching every moment.

Ditha didn’t move or speak.

A grumpy voice barked, “His mother was also a great lover! She taught our youth.”

Then another voice was heard, nasal and unmanly: “She shared the fierce load of our teens. Maybe she taught Ditha some tricks to woo the beggar-woman!”

The villagers roared with laughter and chatted as Ditha’s heart sank under the barbed laughter. When he got up and left, it seemed as if he felt free from the burden of love. He resumed his duties carrying his water pitchers, wearing a big smile as though nothing unusual occurred. He reverted to his former self as he wore unwashed clothes and let his hair grow wildly. No one saw him near the beggars’ huts after that night. At night, I often observed, he’d get in his cold bed and sob himself to sleep. I left him sobbing, in villager’s charge, in pursuit of my education and career.

********

I found a job and settled in a city, leaving the past behind. Then it arrived: an invitation to my cousin’s wedding back in the village. All I could think of was Ditha. I never forgot him. I returned, but I could not find him. I demanded to know where he was.

The words hit me, hard and cold, like a bullet through my heart. Tuberculosis was about to finish him. But the worst was that he had been left to suffer in some hut outside the village. I was fuming. How dare they leave him to die!

I demanded a doctor accompany me to see him, but the doctor refused, and when I approached other doctors, withering glances and flat denials met me. It seemed no servant’s life was worth the inconvenience, no visit to a donkey-man worth the social demotion .

I found him lying alone in the far corner of the dark, cold hut—dark and cold, just like the villagers. I struggled to breathe through the stench of mold and earth, but I pushed forward for him, for my friend.

At first, he did not recognize me. Once he did, he began to weep. He attempted to speak, but the congestion in his lungs was too much and he remained silent. It was difficult for him to breathe, let alone speak.

“Ditha, don’t worry.” I choked back my tears. “I’ll take you to see a doctor tomorrow. You’ll be all right. Let me get some blankets.”

I gave his hand a tight squeeze then hurried to the door, but a gurgled plea stopped me. Turning, I saw the shadow of death on his face. He motioned me to his side; I hurried to kneel down beside him. In a weak, rasping voice, he whispered words that haunt me still: “life will go on whether I’m a part of it or not.”

“Don’t forget me.” His eyes begged as I left.

“I won’t Ditha, I won’t,” I whispered, so lightly that the wind carried my words and scattered them—never to be heard by anyone else. As I walked, I wanted so badly to turn around and look at him. I wanted to see him again. But, I resisted the urge in my heart, forcing myself to look straight. I wouldn’t look back. Ditha expressed a sweet smile to all, but there was no one to return that, at least when he was dying.

He passed away that night and was consigned to the grave the next morning. There was no ceremony, no final rites or words of remembrance. He was forgotten; it was as if he never existed. There was nobody to hear his stories, no one to know him for his true self. Before his burial, I saw him one last time. He still smiled, as if to tell me, “Death isn’t as horrible as you might think.”

They buried him next to strangers in the cemetery. Most of the villagers would have preferred him to be buried with the animals. I sighed: he may have liked that better.

********

I blink tears and shake myself from my solemn stupor. The poor, dying donkey is before me, swimming slowly back into focus. I reach to put my hand on his head as his struggles grow weaker. He too is dying.

So like dear Ditha, I whisper, and immediately regret my words. No! Allah Ditha was a man. Would God allow that we could all be such a man?

I am so moved by the story "THE MAN WHO DIED SMILING"! Muhammad Nasrullah Khan is a fine writer of this deep social truth.

Thank you very much for your encouraging comments, Susan. Appreciated!