By

Joe Khamisi

When I arrived in the United States for the first time in the late 1960s, Richard Nixon was the President, Martin Luther King Jr. was dead, and American cities were embroiled in street riots by blacks angered by high levels of unemployment, poverty, and social discrimination.

“The Chicago Seven,” a group of radical Black Panther activists, among them Bobby Seale, Eldridge Cleaver, and Huey Newton, was in court facing prosecution for a variety of offences including plots to bomb public buildings; and everywhere in the country students were demonstrating and engaging in sit-ins on the streets and in university campuses.

The black revolutionary and civil rights activist, Angela Davis, was electrifying crowds with her black power message before she went underground to escape arrest. She was captured in 1971 and taken to court on conspiracy, attempted kidnapping and murder charges. A year later she was acquitted.

In some parts of the country whites were attacking buses carrying black children to stop integration of schools, while white supremacist groups like Ku Klux Klan were rekindling support for segregation among racist whites.

In those decades of the 60s and 70s, race relations were at their lowest ebb in the United States. Many cities were under siege and the National Bureau of Economic Research says the disturbances of the time were “unprecedented in their frequency and scope.”

Now in the 2000s, we see a resurgence of similar extreme forms of racial animosity. Black/White tension has risen in most parts of the country and street demonstrations are more frequent now than they were a few years ago, with deadly consequences. The proliferation of guns is not helping to calm the situation either. One estimate puts 88 guns in the hands of every 100 Americans – a staggering reality.

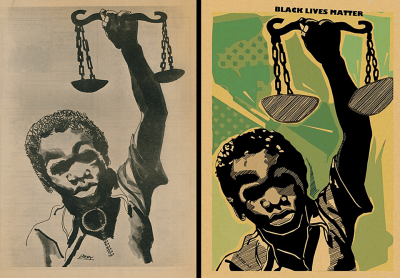

Some of the violence is triggered by killings of young black males by police; some are revenge shootings against policemen by angry black civilians. But looking at events today, the situation is not as bad as it was forty or fifty years ago. It is just eerie and morose. The actions of the Black Lives Matter movement, to my opinion, are a far cry from the violent activities of the Black Panthers. Generally, things have improved though relations between blacks and law enforcement agencies remain acrimoniously sour. The Huffington Post reports 136 black people have been killed by police so far this year.

Photo – Emory Douglas

And as officials say, there is a lot of hurt and grieving on both sides of the color divide and healing is urgently required. But racial harmony cannot be achieved on the streets.

I have decided to dwell on this subject this week, not necessarily because of what happened recently, but because of a post I saw in the social media this week which tells a story of anguish and despair among African Americans. A group under the tag name ‘We Want to Go Home’ is collecting signatures to support a petition to African countries asking them to open doors to African Americans wishing “to go back” to the continent from where their ancestors came centuries ago.

“We are simply asking that we have the opportunity to return to the birthplace of our ancestors in order to try rebuild and heal our trauma,” says the petition in part. Whether this initiative is based on the African American experiences of recent years is hard to tell. But it has all the hallmarks of the Black to Africa movement of Marcus Garvey in the 1880s.

WWTGH, which is featured under the domain name Change.org, is led by Brenda Pearson, an activist and writer; and as I am writing, the group is about to reach its target of 2,500 signatures which are to be sent with a letter to all the African countries. It will be interesting to see what the Africans think about this initiative.

So far, only Ghana has accommodated returning African Americans. There are 3,000 of them who live, own properties, and run businesses in that West African country.

The question is: Will asylum in Africa solve the problems of the “traumatized” African Americans?

Maybe, maybe not. Let’s talk.

And that is my say.

Joe Khamisi

Joe Khamisi is a former journalist, diplomat and Member of Parliament. He is also the Author of ‘Politics of Betrayal:Diary of a Kenyan Legislator‘, a political memoir about the situation in Kenya between 2001, when the ruling party of President Daniel Arap Moi, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), merged with Raila Odinga’s National Development Party.

The book also narrates cases of corruption in Parliament and in the Media and records Senator Obama’s visit to Kenya in 2006. As a friend of Barack Obama Senior, the author also remembers the times and tragedies of the American-educated economist.

Joe Khamisi’s second book, a biography, ‘Dash Before Dusk’ is also now on sale.

Joe’s latest book is ‘The Wretched Africans: A Study of Rabai and Freretown Slave Settlements‘ which has recently been published and is now available to purchase.

I think that part of the in America is that expectations of African-Americans were raisedby the election of Barack Obama. For various reasons, it was impossible for the President to fulfill those expectations. This situation is not restricted to the US. You can also see it in formerly white-dominated African countries such as South Africa. The failure of successive Black African governments in South Africa to substantially raise Black living standards has led many Black South Africans to question the benefits of Black majority rule. There is, of course, no simple solution or quick fix. Black America and Black South Africa, need white-dominated capital to invest in infrastructure and create employment. Too much emphasis on positive discrimination has the effect of driving out capital which creates problems similar to those being experienced in countries such as Zimbabwe.