By

Rupen Savoulian

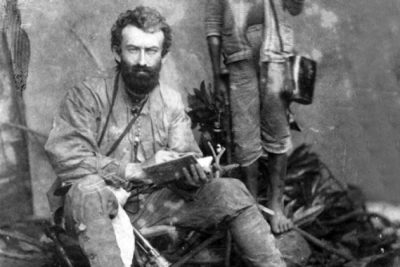

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay (1846-1888) was a Russian anthropologist, biologist and explorer who lived and worked in Sydney, NSW for a total of nine years, establishing himself as a respected member of the NSW scientific community.

He created the first biological research station in the Southern Hemisphere, and made important contributions to the Linnean Society, the main scientific and natural history institute in the self-governing British colony of NSW at the time. He married the daughter of the five-times Premier of NSW, John Robertson. That should have solidified Miklouho-Maclay’s position in the Sydney scientific community and earned him a place in our history. However, he is largely forgotten, and his story has been revived through the efforts of researchers and historians, who compiled a fascinating documentary about him for the ABC in 2013 called ‘Remembering Nikolai’.

There is a large reason why he has been ignored – Miklouho-Maclay lived and worked among the indigenous peoples of Papua and New Guinea for three years, and championed the rights of the native nations to resist colonisation. Why is that important?

In the 1870s and 1880s, both the British colonies of Queensland and NSW were eyeing the natural resources of Papua and New Guinea for themselves. The Australian colonies, while not politically organised into a federation, were expanding on a capitalist basis. The Pacific islands, Polynesia and Melanesia were viewed as unexplored and untamed frontiers. NSW and Queensland lobbied the British government to colonise Papua and New Guinea. European colonisation of indigenous people and territory was in full swing in the late nineteenth century. The English, Germans, Dutch and French were already grabbing portions of the South Pacific and Asia – Melanesia was in their sights. Germany had set up a colony in the northern half of New Guinea, and the Queensland government strongly urged the British to get their foothold in the southern half of Papua.

Queensland’s ruling landed gentry, and to a certain extent, NSW – engaged in the practice of blackbirding. This involved the forcible recruitment, through kidnapping and trickery, of Melanesian workers into a scheme of indentured labour. Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, Papua – the indigenous people of these nations were forced into a system of slavery, working in the sugar cane plantations and landed estates in Queensland and NSW. The full story of blackbirding is still being literally uncovered until today. As Jeff Sparrow explains in his article for The Guardian:

Between 1863 and 1904, 62,000 South Sea Islanders were brought to Australia, landing in Brisbane, Maryborough, Bundaberg, Rockhampton, Mackay, Bowen, Townsville, Innisfail and Cairns. The majority of the indentured labourers came from today’s Vanuatu, with a substantial proportion from the Solomons, as well as smaller islands. Some came voluntarily (even accepting multiple trips). Others did not – and varying degrees of deception and outright coercion were used by blackbirders to persuade them.

By the 1890s, the so-called “Kanakas” were providing 85% of the workforce for the sugar industry.

What has all this got to do with Miklouho-Maclay?

Nineteenth century European anthropology was the hey-day of pseudo-scientific racism; the belief that different human races represented different species, and could be organised hierarchically into an evolutionarily-upward structure, with the lower races – such as the indigenous peoples of Polynesia and Melanesia – at the lower end of the spectrum, and the white race, the colonisers at the top. Anthropology was used in the service of this colonising project, with pseudo-scientific devices such as phrenology and craniometry provided a veneer of respectability to a new imperial endeavour of systematic racism. Into this environment, Miklouho-Maclay worked tirelessly to refute this pseudo-scientific nonsense.

In a powerful article for Russia Beyond the Headlines, Miklouho-Maclay’s unending efforts in defending the colonised people are discussed at length. Early in his career, he travelled to the Canary Islands as an assistant to the great German biologist Ernst Haeckel. The latter espoused the pseudo-scientific racist views prevalent at the time, and Miklouho-Maclay was determined to disprove these supremacist theories. Europeans certainly did believe in liberty, equality and fraternity – as long as you were white.

Miklouho-Maclay was the first white man to settle and work among the indigenous Papuans – he moved there in 1871 and worked for three years among people deemed cannibals and flesh-eating savages. He formed close bonds with the people there, noting their complex societal structures and learned one of their many languages. He continued his ethnographic studies, and provided ample refutation of the predominant racism of his time. He wrote the following, quoted in the Russia Beyond the Headlines article above that:

“There is no ‘superior’ race,” Miklouho-Maclay wrote after finishing his research in Papua New Guinea. “All races are equal because all people on Earth are the same biologically. Nations merely stand upon different steps of historical development. And the duty of each civilized nation is to help the people of a weaker nation in their quest for freedom and self-determination.”

While making Sydney his second home, Miklouho-Maclay spoke out against the rising tide of colonisation, and criticised the push by his adoptive home to make Papua New Guinea an economic colony. Distrust of the newcomer turned into outright hostility, as he maintained his opposition to the new imperialism, driven by economic interests in the emergent colonies of NSW and Queensland. His campaign to defend the targets of creeping colonisation was examined in a biographical program on him for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). That program quoted his words on the issue of Papuan annexation. Miklouho-Maclay spoke of his time living in Papua New Guinea:

During my stay among the natives… I had ample time to make acquaintance with their character, their customs, and institutions. Speaking their language sufficiently, I thought it my duty as their friend (and also as a friend of justice and humanity) to warn the natives… about the arrival, sooner or later, of the white men, who, very possibly, would not respect their rights to their soil, their homes, and their family bonds.’

He went on, ‘should annexation of the south-eastern half of New Guinea be decided by the British Government, I trust it will not mean taking wholesale possession of the land and its inhabitants without knowledge or wish of the natives, and utterly regardless of the fact that they are human beings and not a mob of cattle.’

‘I am perfectly convinced that acts of injustice from the white men, and disregard of their customs and family life, will lead to an irreconcilable hatred, and to an endless struggle for independence and justice.’

Sadly, the tide of colonisation was too strong, and the British did eventually carve out a portion of New Guinea, taking possession without the consent of the indigenous inhabitants. At the end of World War One, Papua New Guinea was handed over to Australia as a colonial possession. With the injustice of this act, the resultant implacable hatred that Miklouho-Maclay warned against was realised. That lead to a prolonged struggle for independence and self-determination in Papua New Guinea.

Ignored by the rising federative colonialism of Australia, Miklouho-Maclay was feted as a hero in his native Russia, and in the subsequent Soviet Union. His fight for racial equality was upheld by the Soviet authorities as a worthy example of a fighting intellectual-scientist. He was acclaimed by the Communist authorities as a man who saw beyond racial differences, and advocated the fundamental equality of human beings. Was this a case of the Soviet authorities exploiting his story for political purposes? In a way, yes. However, his life and work were celebrated during Tsarist Russian times, and his contemporaries, such as the great Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, also sang his praises.

Tolstoy was moved to write about Miklouho-Maclay that, “You were the first to demonstrate beyond question by your experience that man is man everywhere, that is, a kind, sociable being with whom communication can and should be established through kindness and truth, not guns and spirits”. Given the serious nature of racism in Russia today, perhaps the current authorities would do well to remember that not so long ago, the Soviets did actually elevate anti-racist scientists such as Miklouho-Maclay into a cultural hero because of his humanist and anti-colonial stand. His life exemplified cross-cultural and multi-racial solidarity.

Miklouho-Maclay is largely forgotten in Australia, because his life and work reminds us of an ugly chapter in the foundational history of the Australian capitalist state. With the unfolding discoveries about our genetic makeup facilitated by the human genome project, science is providing irrefutable evidence that there is no scientific validity for racism. However, we must confront the racism that exists in our own society, a racism that is damaging and ruining people’s lives everyday.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!