By

Rupen Savoulian

In October of this year, a statue of Mahatma Gandhi was removed from the grounds of the University of Ghana, only a few months after it had been erected there as a presentation from the visiting Indian President, Pranab Mukherjee.

This statue was removed after a petition by Ghanaian scholars and academics, who pointed out that Gandhi, during his stay in South Africa, made racist statements towards black Africans, and that his example was inappropriate for modern-day Ghanaians. In an article for The Guardian newspaper, Jason Burke elaborates on the reasons why the petitioners were outraged by the prominence of the Gandhi statue:

The petition states “it is better to stand up for our dignity than to kowtow to the wishes of a burgeoning Eurasian super power”, and quotes passages written by Gandhi which say Indians are “infinitely superior” to black Africans.

More than 1,000 people signed the petition, which claimed that not only was Gandhi racist towards black South Africans when he lived in South Africa as a young man, but that he campaigned for the maintenance of India’s caste system, an ancient social hierarchy that still defines the status in that country of hundreds of millions of people.

The Gandhi statue – the target for removal amid claims Gandhi was racist towards black Africans

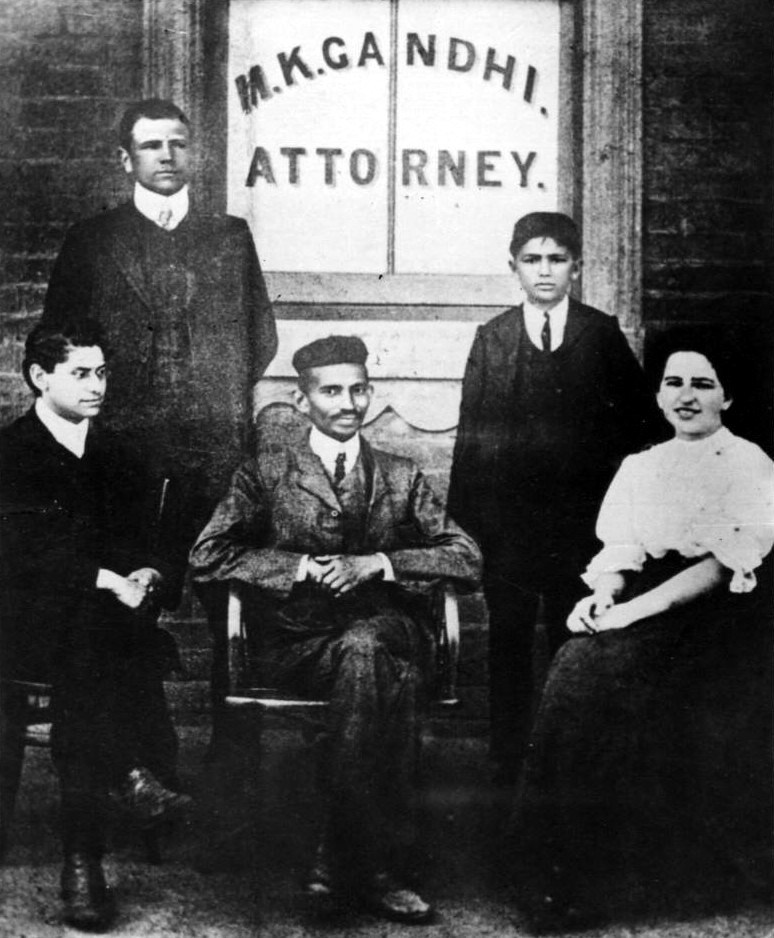

Gandhi’s life in South Africa, where he worked as a barrister defending the rights of the Indian community, is the subject of numerous scholarly works and articles. He spent twenty-one years of his life there, confronting an apartheid regime of strict racial discrimination, long before the authorities in Pretoria used the word ‘apartheid’ to describe their racially stratified society. His South African period is especially of relevance – why? This controversy around the Gandhi statue in Ghana arrives hot on the heels of a similar dispute that erupted back in March 2015 – Rhodes Must Fall.

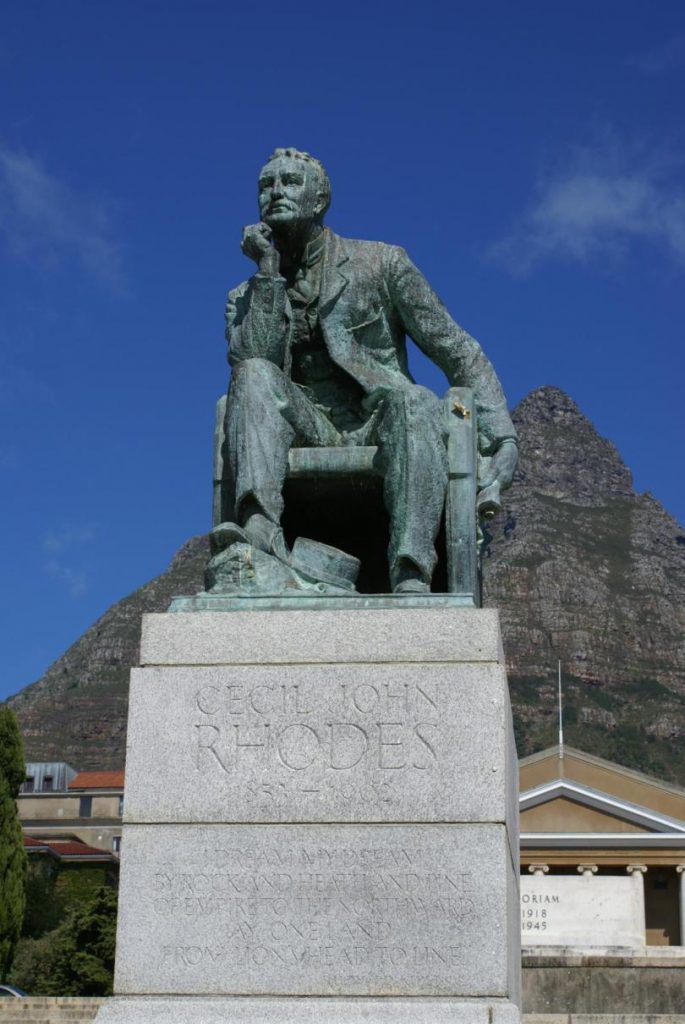

Students and lecturers from the University of Cape Town, South Africa, began a campaign to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes, British empire-builder and racist entrepreneur-coloniser, from their campus. The campaign to remove the statue began a series of thoughtful and serious questions about the decolonisation of education, the progress (or lack thereof) of racial and economic equality in the post-apartheid South Africa, and the nature and role of the former British empire. A vociferous campaigner for British imperial rule, Rhodes founded the British South Africa Mining Company for the purpose of exploiting the rich mineral wealth of southern Africa.

Rhodes, whose name was given to the country of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) openly expressed his motivations for empire-building – the superiority of the English people, as he saw it. He loudly and repeatedly expressed the view that British settler-colonialism was the highest priority for the British people, because the British were the ‘first race’ in the world. He made plain his disdain for whom he viewed as lesser races, namely, the black African people.

Cecil Rhodes statue at the University of Cape Town – removed in April 2015 after student protests

Dying in 1902, Rhodes was unrepentant to the end, never wavering in his view that blacks must be ruled over by a class of wealthy whites. His history is one of racial hatred, treachery and deception in amassing enormous reserves of wealth and waging vicious wars against millions of black Africans. Rhodes is remembered today, if at all, for funding the scholarship that bears his name. Such a programme was intended to fund the brightest and best students from all of Britain’s colonial possessions, for the purpose of studying at elite British educational institutions. Australians can appreciate the academic calibre of Rhodes scholars until today, having made a lasting impact on Australian society with their superior intellectual skills.

Be that as it may, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign highlighted the importance of addressing racial and economic iniquities, not for the purpose of self-flagellation, but for the purpose of redressing historical grievances. Rhodes and his role in creating the regional dominance of the British empire should never be erased from the historical memory – Rhodes Must Fall wants the world to know his crimes for the purpose of re-evaluating the legend that has surrounded Rhodes and his impact since his death. Every historical figure, including Rhodes and Gandhi, accumulate a vast body of myths and half-truths after they pass on – whether deliberate hagiography or the product of rose-tinted views of their work. Each person must be evaluated, if only to fully appreciate their achievements and weaknesses. Rhodes was a racist land-hungry imperialist, and for that reason, his statue must fall.

If that is case, should not Gandhi’s statue also fall? Did he not make racist comments and statements about black Africans during his time in South Africa? Did he not support the British empire, going so far as to work as a stretcher-bearer for British forces in their war against the Boers in the early part of the twentieth century? Gandhi himself created and joined the Indian Ambulance Corps for the express purpose of providing service to the British military forces during the Boer War.

Mahatma Gandhi in the uniform of a sergeant as the leader of Indian Ambulance Corps

Gandhi, during his South African stay, made numerous statements that can only be interpreted as racist comments against black Africans. He was only concerned with the status of the Indian community in that country, and sought to improve their standing by cooperating with the British authorities. He intended to prove to his white counterparts that the Indian was unjustly dismissed as a ‘savage’ and ‘brute’, no better than a kaffir – the latter a derogatory term referring to black Africans. For instance, in his voluminous writings, you may find statements such as this:

A general belief seems to prevail in the Colony that the Indians are little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa. Even the children are taught to believe in that manner, with the result that the Indian is being dragged down to the position of a raw Kaffir.

In 1904, he wrote to the authorities in Johannesburg to complain about the mixing of Indians and Kaffirs in an unhealthy slum section denoted ‘Coolie location’, and he claimed that disease and epidemics would surely persist if this unsanitary mixing continue. Gandhi made various statements denouncing the heathen-beliefs of the black Africans, and strenuously sought to distinguish the Indian as an educated and civilised contributor to the British empire, unlike the ostensibly primitive black African. In 1893, soon after arriving in Natal, Gandhi wrote that:

“I venture to point out that both the English and the Indians spring from a common stock, called the Indo-Aryan. … A general belief seems to prevail in the Colony that the Indians are little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa. Even the children are taught to believe in that manner, with the result that the Indian is being dragged down to the position of a raw Kaffir.

He arrived in what was then Natal colony, South Africa, in May 1893 an inexperienced and politically immature lawyer. He persistently couched his appeals to British authority in terms of the superior values of the Indian – in contrast to the black African. There is no question that Gandhi absorbed and reflected the prejudiced attitudes and values of his day and community. Gandhi’s grandson and biographer, Rajmohan Gandhi, admitted that his famous grandfather was at times ignorant and prejudiced about black Africans. As the author E S Reddy stated in an article for The Wire magazine:

The class and colour prejudices Gandhi carried from India were reinforced by those of the merchants and the white officers he dealt with. In countering the arguments of the white racists, he tried to show that Indians, unlike the Africans, had an ancient civilisation. He used the language of the whites, which was offensive to Africans, and referred to them as ‘kaffirs.’

Gandhi in Johannesburg seated in front of his law practice – 1905

Throughout his stay, he witnessed the many injustices done to the black African community, and the exploitative nature of the British empire. As he matured in years and political outlook, he began to take steps on the path that made him an agent of social and political change. Gandhi developed and refined the doctrines and practices of non-violent civil resistance which are today an inspiration for political leaders and people world-wide. Indeed, it is worth recalling the words of Nelson Mandela, and his analysis of Gandhi. For instance, in 1995, after his release from prison, Mandela wrote the following:

Gandhi must be forgiven those prejudices and judged in the context of the time and circumstances. We are looking here at the young Gandhi, still to become Mahatma, when he was without any human prejudice save that in favour of truth and justice.

He also stated in 2003 that:

Gandhi’s political technique and elements of the nonviolent philosophy developed during his stay in Johannesburg became the enduring legacy for the continuing struggle against racial discrimination in South Africa. (Speech made during the unveiling of the statue of Gandhi in Johannesburg in October 2003).

As Gandhi took up the cause of his community in South Africa, he began to recognise the injustices of the racially and economically stratified society against which he and his supporters were fighting. The Boer war (1899-1902), during which the British armed forces committed numerous atrocities on the white South African minority, was a politically awakening experience for those who emerged from this trauma – Gandhi included. Non-white political organisations, paradoxically, were given a boost by the bitter experiences of this war. As the South African statelets – Natal, Transvaal and so on – moved towards establishing a national entity in the early years of the 1900s, the non-white communities found themselves collectively marginalised. In this context, witnessing the brutality of white-only rule against the indigenous and non-white populations served as a political awakening for the young Gandhi.

As the Indian community mobilised for their rights in the new South Africa, Gandhi started to widen his political horizons, declaring in a speech that:

South Africa would probably be a howling wilderness without the Africans…

If we look into the future, is it not a heritage we have to leave to posterity that all the different races commingle and produce a civilisation that perhaps the world has not yet seen.

In 1912, the South African Native National Congress was formed – the predecessor of the African National Congress. Gandhi welcomed this development, and never sought to impose his example or leadership upon it. He only offered his philosophy of satyagraha – insistence on truth – as a method to combat racial oppression.

Years later, after Gandhi had returned to India to struggle against the British rule over his native country, he made statements to demonstrate that his interest in and support for South Africa never wavered. In a speech to Oxford university in 1931, he declared:

As there has been an awakening in India, even so there will be an awakening in South Africa with its vastly richer resources – natural, mineral and human. The mighty English look quite pygmies before the mighty races of Africa. They are noble savages after all, you will say. They are certainly noble, but no savages and in the course of a few years the Western nations may cease to find in Africa a dumping ground for their wares.

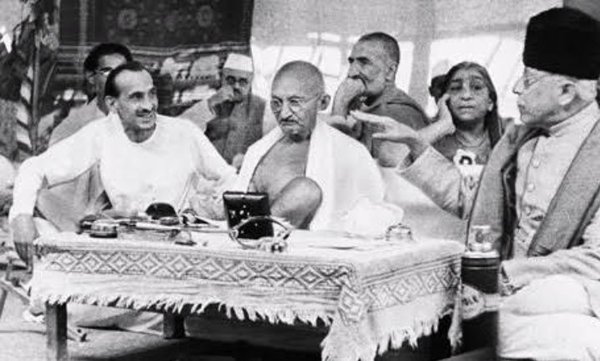

Gandhi surrounded by his supporters – August 1942

Having learnt from the experience of anti-colonial nationalism, Gandhi applied himself to the struggle in India for home rule. One of his lifelong comrades and staunchest supporters, Jawaharlal Nehru, not only learned from Gandhi’s example, but applied it to all oppressed groups. From the 1920s onwards, Nehru advocated the necessity of uniting on a multi-ethnic and pluralist basis, including oppressed people of all colours in the struggle against colonialism. He went on to become the first post-independence Indian prime minister, as well as the architect and leader of the Non-Aligned Movement.

The non-aligned anti-colonial movements encompassed all races and ethnic groups for the common purpose of self-determination. One of the main exponents and practitioners of anti-colonial liberation was a black African political leader, Kwame Nkrumah – who lead his country, today known as Ghana, to independence. Nkrumah was a socialist and pan-Africanist, who derived inspiration from numerous sources. One of the sources from which he learned and drew inspiration was Mahatma Gandhi, whose doctrines of non-violence and non-cooperation profoundly influenced the Ghanaian anti-colonial campaign. It is obviously up to the authorities at the University of Ghana to decide whether or not to keep the statue of Gandhi on their campus. No-one can dispute that. However, rejecting Gandhi’s example would be a huge disservice to all those – from all races – who drew inspiration from the Gandhian model in their own anti-colonial struggles for self-determination.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!