Archibald J. Motley, Jr.

By

Durodola Tosin

INTRODUCTION

The Roaring Twenties were times of rapid change, culturally and socially, artistic innovation, and high-society antics. Popular culture roared to life as the economy boomed. New technologies, soaring business profits and higher wages allowed many Americans to purchase a wide range of consumer goods. Prosperity also provided Americans with more leisure time, and as play soon became the national pastime, literature, film, and music caught up to document the times. Much of the drift for this modernization came from America’s second Industrial Revolution, which had begun around the turn of the century.

During this era, electricity and more advanced machinery made factories nearly twice as efficient as they had been under steam power in the 1800s. Perhaps the greatest increase in efficiency came when Henry Ford perfected the assembly-line production method, which enabled factories to invent large quantities of a variety of new technological wonders, such as radios, telephones, refrigerators, and cars. The increasing availability of such consumer goods pushed modernization forward, and the U.S. economy began to shift away from heavy industry toward the production of these commodities.

The automobile quickly became the symbol of the new America. Although Americans did not invent the car, they certainly perfected it. Much of the credit for this feat went to Ford and his assembly-line method, which transformed the car from a luxury item into a necessity for modern living. By the mid-1920s, even many working-class families could afford a brand-new Model T Ford, priced at just over $250.

Increasing demand for the automobile in turn trickled down to many other industries. The demand for oil, for example, boomed, and oil prospectors set up new wells in Texas and the Southwest practically overnight. Newer and smoother roads were constructed across America, dotted with new service stations. Change came so rapidly that by 1930, almost one in three Americans owned cars. Its effect on the U.S. economy aside, the automobile also changed American life immeasurably.

Cars most directly affected the way that Americans moved around, but this change also affected the way that Americans lived and spent their free time. Trucks provided faster modes of transport for crops and perishable foods and therefore improved the quality and freshness of purchasable food. Perhaps most important, the automobile allowed people to leave the inner city and live elsewhere without changing jobs. During the 1920s, more people purchased houses in new residential communities within an easy drive of the metropolitan centers. After a decade, these suburbs had developed immensely, making the car more of a necessity than before.

Cities in America have changed drastically during the 1920s because of factors above and beyond those related to the automobile. First, the decade saw millions of people flock to the cities from country farmlands; in particular, African Americans fled the South for northern cities in the post–World War I black migration. Immigrants, especially eastern Europeans, also flooded the cities. As a result of these changes, the number of American city dwellers—those who lived in towns with a population greater than 2,500 people—came to outnumber those who lived in rural areas for the first time in U.S. history. Consecutively, new architectural techniques allowed builders to construct taller buildings. The first skyscrapers began dotting city skylines in the 1920s, and by 1930, several hundred buildings over twenty stories tall existed in U.S. cities.

Aviation developed quickly after the Wright brothers’ first sustained powered flight in 1903, and by the 1920s, airplanes were becoming a significant part of American life. Several passenger airline companies, subsidized by U.S. Mail contracts, sprang to life, allowing wealthier citizens to travel across the country in a matter of hours rather than days or weeks. In 1927, stunt flyer Charles Lindbergh soared to international fame when he made the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean (from New York to Paris) in his single-engine plane, the Spirit of St. Louis. His achievement gave an enormous boost to the growing aviation industry.

Radio was highly influential during this period, which entertained and brought Americans together like nothing else had before. Electricity became more readily available throughout the decade, and by 1930, most American households had radio receivers. The advertising industry blossomed as companies began to deliver their sales pitches via the airwaves to thousands of American families who gathered together nightly to listen to popular comedy programs, news, speeches, sporting events, and music. In particular, jazz music became incredibly popular. Originating in black communities in New Orleans around the turn of the century, jazz slowly moved its way north and became a national phenomenon thanks to the radio. Along with new music came “scandalous” new dances such as the Charleston and the jitterbug.

Against the background of the foregoing, this paper sets for itself the task of describing how apt is the description of the 1920’s in America history as the Jazz age. Among other things the paper will examine the rise and birth of Jazz in America and also the events that help spread jazz in America. Finally, an attempt will be made to see how effective Jazz music was during the 1920’s. But first how did Jazz music emerge? Put differently, did the effect of the Great depression necessitate the emergence of Jazz music in America?

JAZZ MUSIC: A SCRUTINY

The Jazz Age was the era in American history that started with the end of WW1 and ended with the Great Depression of 1929 when jazz music, modern ideas, flappers and dance became popular. The decade known as the Jazz Age was the 1920’s, also known as the Roaring Twenties. This movement coincided with both the equally phenomenal introduction of mainstream radio and the conclusion of World War I. Although the era ended as the Great Depression victimized America in the 1930’s, jazz has lived on in American pop culture. The movement spread across the United States, especially in the cities like Chicago and New York, and eventually hit England and other European countries. With the growing popularity of radio, music was able to spread quickly, becoming popular across the entire nation. People also had greater mobility starting in the 1920s, as owning a car became commonplace. The movement of people added to the far range of fads and culture, like dances, and music.

The Jazz Age was the term coined by F. Scott Fitzgerald to describe the flamboyant “anything goes” era that was a feature of the 1920s. Jazz music, characterized by improvisation, syncopation, and a lively, strong rhythm, was introduced during the Harlem Renaissance, the African-American artistic and literary movement. Jazz music somehow typified the nonconformist aspirations of youth that dominated the shocking new fashions and lifestyles that emerged during the 1920’s “Jazz Age”. This occurred particularly in the United States, but also in Britain, France and elsewhere.

Jazz played a significant part in wider cultural changes during the period, and its influence on pop culture continued long afterwards. Jazz music originated mainly in New Orleans, and is/was a fusion of African and European music. The Jazz Age is also referred to in conjunction with the Roaring Twenties. The “Jazz Age” was a period of many political, economic and social changes when Americans cast aside old social conventions in favor of new ideas, embracing the rapid cultural and social changes of modernism and the flamboyant lifestyles of the new era.

The birth of jazz music is often accredited to African Americans, but both black and white Americans alike are responsible for its immense rise in popularity. Those people who opposed Jazz saw it as music of people with no training or skill. White performers were used as a vehicle for the popularization of jazz music in America. Even though the jazz movement was taken over by the middle class white population, it facilitated the mesh of African American traditions and ideals with the white middle class society. Cities like New York and Chicago were cultural centers for jazz, and especially for African American artists. People who were not familiar with Jazz music could not recognize it by the way Africans Americans wrote it.

Furthermore, the way African Americans writers wrote about Jazz music, made it seem as though it was not a cultural achievement of the race. Some famous black artists of the time were Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie. Several musicians grew up in musical families, where a family member would often teach how to read and play music. Some musicians, like Pops Foster, learned on homemade instruments. Louis Armstrong’s talent on the trumpet, scat abilities, and distinctive voice made him a favorite across all demographics, influencing the genre for generations to come.

Bessie Smith and Ella Fitzgerald were two of the most prominent female singers of the 1920s and 1930s respectively. Bessie Smith was one of the most prominent Blues singers at the time, which along with Louis Armstrong, strongly influenced the Jazz genre, especially for future stars like Billie Holliday. Ella Fitzgerald was also known as “First Lady of Song” and was also a vocalist and scat singer. Other prominent musicians of the Jazz scene were Fats Waller, and Duke Ellington.

EVENTS THAT HEIGHTENED THE SPREAD OF JAZZ

RADIO STATIONS

Urban radio stations played African American jazz more frequently than sub-urban stations, due to the concentration of African Americans in urban areas such as New York and Chicago. Jazz began in African Americans societies, but soon spread to middle-class white communities, where the style continued to evolve. The popularity and acceptance of Jazz music benefited the African American community, as many white people began accepting parts of African American culture and, in turn, accepting members of the African American community. Contact between African Americans and middle-class white people increased, which helped both sides mesh.

Female musicians such as Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday emerged during this period of post-war equality and free sexuality, paving the way for future female artists. Younger demographics popularized the black-originated dances such as the Charleston as part of the immense cultural shift the popularity of jazz music generated. The migration of African Americans from the American south introduced the culture born out of a repressive, unfair society to the American north where navigating through a society with little ability to change played a vital role in the birth of jazz.

YOUTH

The youth of the 1920s was influenced by jazz to rebel against the traditional culture of previous generations. This youth rebellion of the 1920s went hand-in-hand with fads like bold fashion statements (flappers), women smoking cigarettes, free talk about sex, and new radio concerts. Dances like the Charleston, developed by African Americans, suddenly became popular among the youth. Traditionalists were aghast at what they considered the breakdown of morality. Some urban middle class African Americans perceived jazz as “devil’s music”, and believed the improvised rhythms and sounds were promoting promiscuity.

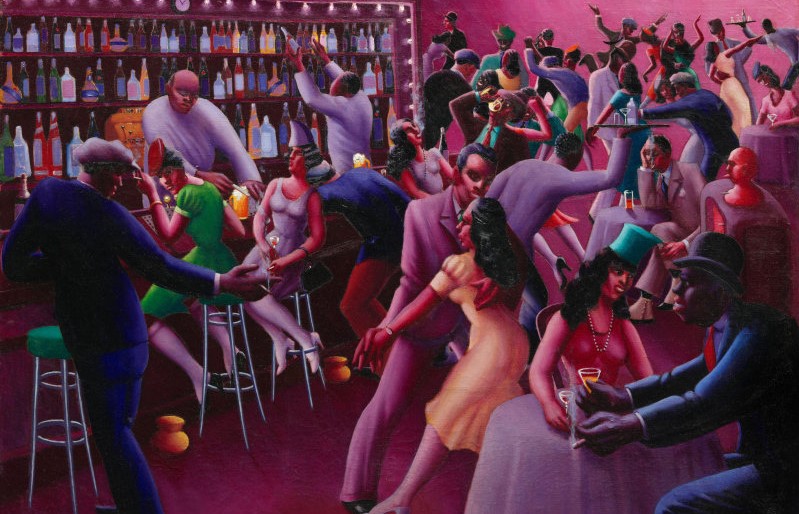

The speakeasies (a place where alcoholic beverages are sold and consumed illegally, especially formerly during Prohibition) around cities were the place people gathered in the evenings to have a drink and have fun. They also became the location of many musical performances, and became a platform for musicians to share their talents. The Cotton Club was a Harlem nightclub where many of jazz music’s legends performed and launched their careers, eventually opening other locations in Chicago and even California.

The Cotton Club was a popular spot for celebrities and rich White people, and while many Black entertainers graced the stage, the Cotton Club refused to allow Black people to enter the club. The Apollo Theater is also in Harlem, and is known for being the biggest venue for Black performers. Ella Fitzgerald began her career on the Apollo’s stage in 1934. The Apollo continued to hold performances long past the 1920s and 30s, and even still has occasional shows.

As jazz flourished, American elites who preferred classical music sought to expand the listenership of their favored genre, hoping that jazz wouldn’t become the mainstream. Controversially, jazz became an influence on composers as diverse as George Gershwin and Herbert Howells.

RADIO AND DANCES

The rise of jazz coincided with the rise of radio broadcast and recording technology, with the most popular radio show being “potter palms” concert and big-band jazz performances. As the 1920’s wore on, jazz, despite competition from classical music, rose in popularity and helped to generate a cultural shift. Dances like the Charleston, developed by blacks, instantly became popular among younger demographics.

With the introduction of large-scale radio broadcasts in 1922, Americans were able to experience different styles of music without physically visiting a jazz club. Through its broadcasts and concerts, the radio provided Americans with a trendy new avenue for essentially exploring the world from the comfort of their living room. These were broadcast from cities such as New York, Chicago, Kansas City, and Los Angeles.

The music of the Jazz Age was introduced to Americans due to the introduction of large-scale radio broadcasts in 1922. Americans could listen to the new style of music without leaving their homes or going to a jazz club in a big city. African American Jazz musicians such as Armstrong initially received very little airtime because most radio stations preferred to play the music of white American jazz singers. Big-band jazz music, like that of Fletcher Henderson and James Reese Europe, attracted large radio audiences.

There were two categories of live music on the radio: concert music and big band dance music. The concert music was known as “potter palm” and was concert music by amateurs, usually volunteers, an amateur concert and big-band jazz performance broadcast from cities like New York and Chicago. This type of radio was a way of making broadcasting cheaper. This type of radio’s popularity started to decrease as commercial radio increased. This type of music is known as big band dance music. This type is played by professionals and was featured from nightclubs, dance halls, and ballrooms. Musicologist Charles Hamm described three types of jazz music at the time: black music for black audiences, black music for white audiences, and white music for white audiences.

Jazz artists like Louis Armstrong originally received very little airtime because most stations preferred to play the music of white American jazz singers. Other jazz vocalists include Bessie Smith and Florence Mills. In urban areas, such as Chicago and New York, African American jazz was played on the radio more often than in the suburbs. Big-band jazz, like that of James Reese in Europe and Fletcher Henderson in New York, attracted large radio audiences. This style represented African Americans in the predominantly white cultural scene. “Jelly Roll Blues” was the first jazz work in print.

AUTOMOBILES

The invention of Auto-Mobiles also helped in the spread of Jazz. Cars gave young people the freedom to go where they pleased and do what they wanted. (Some pundits called them “bedrooms on wheels”). What many young people wanted to do was dance: the Charleston, the cake walk, the black bottom, the flea hop. Jazz bands played at dance halls like the Savoy in New York City and the Aragon in Chicago; radio stations and phonograph records (100 million of which were sold in 1927 alone) carried their tunes to listeners across the nation. Some older people objected to jazz music’s “vulgarity” and “depravity” (and the “moral disasters” it supposedly inspired), but many in the younger generation loved the freedom they felt on the dance floor.

FEMALE ARTISTS

Female musicians such as Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday emerged during this period of post-war equality and free sexuality, paving the way for future female artists. The surfacing of flapper women also began to captivate society during the Jazz Age, a time in which many more opportunities became available for women. At the end of the First World War, many more possibilities existed for women in the work force, in their social lives and especially in the entertainment industry.

With women’s suffrage at its peak with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, and the entrance of the flapper, women began to make a statement within society and the Jazz Age was not immune to these new ideals. With women now taking part in the work force after the end of the First World War there were many more possibilities for women in terms of social life and entertainment. Ideas like equality and free sexuality were very popular during the time and women seemed to capitalize during this period.

Another exception to the common stereotype of women at this time was piano player Lil Hardin Armstrong, Louis Armstrong’s wife. She was originally a member of King Oliver’s band with Louis, and went on to play piano in her husband’s band the Hot Five and then his next group called the Hot Seven. It was not until the 1930s and 1940s that many women jazz singers, such as Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday were recognized as successful artists in the music world. These women were persistent in striving to make their names known in the music industry and lead the way for many more women artists to come.

HARLEM RENAISSANCE

This period also witnessed the Harlem Renaissance. Jazz music was influenced mainly by styles from the South, but the movement caught on and eventually traveled around the whole United States and even parts of Europe. The centers for jazz music were in New York City and Chicago. New York City’s famous borough, Harlem, was the heart of the Harlem Renaissance, with venues like the Cotton Club, where jazz musicians performed every night.

The Harlem Renaissance, the “flowering of Negro literature” was centered in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City. Harlem was originally a Dutch settlement. Beginning in around 1910, around 2 million blacks relocated from the U.S. South to the North, in what became known as the (first) Great Migration. There was a general movement of both black and white people from small, rural towns to big cities during this time period, since it was easier to find jobs and opportunities in the city. Many of the 2 million blacks who relocated to the North chose New York City as their destination, eventually settling down in Harlem, partly because of residential discrimination in white neighborhoods. They were not only looking for better opportunities in the North, but also hoping to escape the racist attitudes of the South.

The cabaret form of entertainment began in New York City and the growing number of speakeasies during the Prohibition era of the 1920’s provided many aspiring jazz musicians with new venues. Duke Ellington arrived in New York City and met his other musicians such as James P. Johnson and Fats Waller. Tin Pan Alley became the center of the music industry in New York City. The Cotton Club was the most famous of all the Harlem nightspots. The community in Harlem became a place of great cultural growth, with the emergence of new musical and literary styles that popularized and gave a voice to the lives and hardships of blacks in the United States.

Both the literature and music appealed not only to blacks, but also to the middle class whites, and helped bridge the distance between the two communities, though many of the older generation resisted. The more rebellious, younger generation who wanted to separate from previous generations, readily embraced jazz music and the new styles of dance. The Harlem Renaissance saw the emergence of a new black identity, and the beginnings of liberation from middle class society’s racism and discrimination.

The Harlem Renaissance saw the emergence of many Black African poets including Claude McKay whose eloquent poetry about American racism included poems such as ‘If we must Die’ and ‘The Lynching’. Langston Hughes, known as ‘The Poet Laureate of Harlem’ wrote ‘The negro speaks of rivers, ‘The Weary Blues’ and ‘I too’ as a response to ‘I hear America singing’ by Walt Whitman.

Also, the most famous book of the Jazz Age era was The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Other notable books were The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway.

CONCLUSION

Jazz music originated with African-American musicians and quickly spread in popularity, it developed in tandem with new commercial radio stations, it allowed for many new opportunities in the entertainment industry, especially for women and blacks, and all of these answers. The 1920s are often referred to as the “Jazz Age” because Jazz music challenged racial segregation and other social issues in American society, it was responsible for many technological innovations, such as commercial radio stations. It emerged as a homogeneous cultural phenomenon that was popular across racial divides, and helped instrument cultural and technological shifts in American society.

Durodola Tosin

Durodola Tosin is an author and writer. He started writing professionally at the age of 12. He was a Columnist in Ekiti Glory Newspaper, Nigeria from 2009-2010. He is the Managing Editor at the Roaring Voice (Online Periodical) and a Freelance Writer for Tuck Magazine.

He has written on several topics like “The Second World War and the economic situation in Africa”, “Africa and the effect of World War II”, “Neo-Colonialism: A Major obstacle to the process of nation-building in Africa”, “Nigeria’s Leadership roles in Africa”, “The Ethnic Setting in the Nigeria Area Before 1800″, ” Terrorism: A New Dimension of War”, “Early African Historians’ Writings Before 1945: Precursors of Modern African Historiography”, “The UN Security Council: Flaws and Obstacles”, “Debt Crisis: A Major Developmental Issue in the Third World Countries”.

Durodola lives in Ekiti State, Nigeria. He holds a Bachelor’s (Hons) Degree in History and International Studies. He is currently writing a book on “Nigeria’s Quest for a Permanent Seat at The UN Security Council” and “Nigeria’s Leadership roles in Africa”.

REFERENCES

http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.delta.edu:2048/stable/pdf/2714928.pdf

https://www.boundless.com/u-s-history/from-the-new-era-to-the-great-depression-1920-1933/the-culture-of-change/the-jazz-age/

http://tdl.org/txlordspace/bitstream/handle/2249.3/269/07_harl_ren_jaz_ag.htm?sequence=13

William Barlow, “Black music on radio during the jazz age,” African American Review (1995) 29#2 pp 325-28 in JSTOR

Biocca, Frank, Media and Perceptual Shifts: Early Radio and the Clash of Musical Cultures, Journal of Popular Culture, 24:2 (1990). pg 9

“The Jazz Age”. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk

http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.delta.edu:2048/stable/pdf/2714928.pdf

Cunningham, et al. Culture & Values: A Survey of the Humanities. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, 2014. Print.

Chevan, David. “Musical Literacy and Jazz Musicians in the 1910s and 1920s.” Current Musicology; Spring 2001/2002; 71-73. Print.

http://m.sparknotes.com/history/american/depression/section2.rhtml

https://www.boundless.com/u-s-history/from-the-new-era-to-the-great-depression-1920-1933/the-culture-of-change/the-jazz-age/

http://tdl.org/txlor-dspace/bitstream/handle/2249.3/269/07_harl_ren_jaz_ag.htm?sequence=13

Biocca, Frank, Media and Perceptual Shifts: Early Radio and the Clash of Musical Cultures, Journal of Popular Culture, 24:2 (1990) pg 3

William Barlow, “Black music on radio during the jazz age,” African American Review (1995) 29#2 pp 325-28 in JSTOR

Savran, David. “The Search for America’s Soul: Theatre in the Jazz Age.” Theatre Journal 58.3 (2006) 459-476. Print.

Paula S. Fass, The Damned and the Beautiful: American Youth in the 1920s (1977) p 22

Dinerstein, Joel. “Music, Memory, and Cultural Identity in the Jazz Age.” American Quarterly 55.2 (2003) 303-313. Print.

Ward, Larry F. “Bessie” Notes, Volume 61, Number 2, December 2004, pp. 458-460 (Review). Music Library Association

Borzillo, Carrie Women in Jazz: Music on Their Terms–As Gender Bias Fades, New Artists Emerge Billboard – The International Newsweekly of hit Music, Video and Home Entertainment 108:26 (29 June 1996) p. 1, 94-96.

Borzillo, Carrie Women in Jazz: Music on Their Terms–As Gender Bias Fades, New Artists Emerge Billboard – The FTW International Newsweekly of hit Music, Video and H’ome Entertainment 108:26 (29 June 1996) p. 1, 94-96.

Biocca, Frank, Media and Perceptual Shifts: Early Radio and the Clash of Musical Cultures, Journal of Popular Culture, 24:2 (1990). pg 9

FURTHER READING

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!