pixabay photo

By

Sepideh Zamani

The woman was screaming. In between her cries and screams she was shouting: “I don’t want… I don’t want… That is enough of daughters; I don’t want any more daughters.”

I was sitting with mum on a foam settee in the waiting room and opposite us a woman in the frame hanging on the wall was holding her index finger in front of her mouth, asking people to be silent. A nurse came out of the room where Maryam was in bed, stood right in front of us and with some hesitancy said: “Your sister-in-law had her baby: a girl.”

Mother, showing her gratitude for this happy news, held her hands towards the skies and said: “Thanks be to God a hundred thousand times!”

I was happy that Maryam, who was my uncle’s wife, had given birth to a girl. But the woman was screaming all the time, rejecting and disowning the girl.

In order not to hear the woman’s voice I casually opened my mouth and yawned and then very loudly began to roar with laughter. Uncle very quickly came and joined us and as if he had heard the news from miles and miles away he put his hand into his pocket and took out whatever bank notes he had and offered them with both hands to the nurse. I said to my uncle: “Have you chosen a name for the baby?”

Uncle said: “Ooh… As many as you would wish for:

Anahita, Camilla, Rose, Ava, but at last we agreed on Ava.”

Ava… Tiny, round and pink.

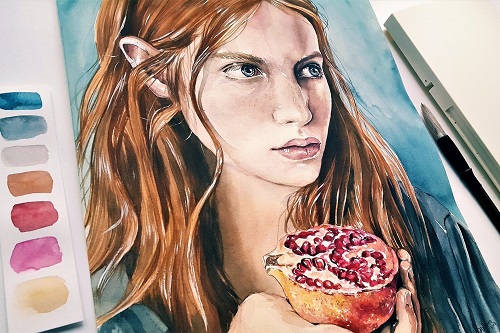

The same day on the way home mum held my hand and we went to our local toy shop and she bought me a doll. And it was instantly named: Pomegranate.

The nurses prepare her to take her to the operating room. We were all dumbfounded and looking at her from behind the glass. My aunt has no strength to say anything and her face is wet with tears. Ava, lifeless and exhausted, raises her head from the trolley and with all her strength says calmly to her mother: “Don’t worry… I will be fine… You said yourself that I will be fine…”

I smile and wave at her and her eyes answer me. She holds the doll closer to her meaning that Pomegranate is with her. I too hold up my Pomegranate and show it to her.

Before going into the operating room she insisted on asking for permission to take Pomegranate with her. At last after going through several administrative hurdles between the medical team and the patient they permitted Pomegranate to be with Ava in this destiny-deciding operation; a destiny that everybody interprets according to the limit and capacity of his brains.

Ava too wanted her destiny to be decided alongside Pomegranate. And what could possibly be better than that a person can press her destiny like the soft cotton body of a doll to her chest.

After a long journey from Iran to Washington for medical treatment for Ava’s illness, they have now arrived here; behind glass windows that were their final gates to hope and expectation. There was no point in being worried any more.

They must be hopeful; hopeful for the outcome of a successful operation on her bone marrow.

Mum had spread a red carpet on the terrace. I was sitting and leaning against the railings. Ava with her tiny body dragged a doll as big as herself next to me. It was a big doll with curly hair that Ava had named Pomegranate. And as I looked at it very carefully I saw that it didn’t look like my doll.

The doll was like her: pale with big eyes. Ava’s colour was also pale. Years of fighting with her illness had made her fragile and tender. She was tired of fighting. She came and sat next to me and touched my hair scattered over my shoulders and said: “How long and lovely! Your hair is so beautiful! I want to grow my hair just like you. I am fed up of being bald. Women don’t get bald…”

She handed me The Little Prince. I said: “Oh no! This book again?” She laughed and said: “Yes, this again!” She then put her mouth on my ear and said: “I’d like to be like you when I grow up.” I said wistfully: “You will look better than me… You just wait and see! With your soft auburn hair everybody wishes to have.” She sat on my knees. I put my hand in her short curly hair and said: “You are cleverer…

More ladylike… More beautiful… When I was your age I was terribly restless and naughty, driving everybody to distraction.

My playmates were Jahan and his friends: they were all boys!

We were climbing walls and trees all the time! Once I fell off a tree and broke my arm. But you are extremely dignified…”

There was a genuine and heartfelt smile on her almost lifeless lips. She asked: “Why are you sniffing me?” I said: “Your smell is like the smell of beautiful colourful flowers in the garden. It is impossible not to sniff you!” I opened the book and began to read: “The Little Prince said:

But now you are going to cry!

Yes, that is so

Then it has done you no good at all!

It has done me good; because of the colour of the wheat fields. Go and look again at the roses. You will understand now that yours is unique in all the world.

My hands are wet with sweat and by the time Davoud answers I have moved the receiver several times from ear to ear. I feel desperate, impatient and irritated till he picks up the phone.

I am going to hospital to visit Ava.

If you wait a little bit, I’ll finish my work.

It will be late by the time you get here. When you finish work come straight there.

A little early or a little late, what difference does it make? Ava is in hospital, in bed and sleeping, so wait until I come. In this traffic it makes sense to use one car instead of two.

A week has passed since the operation and she still can’t receive any visitors. We have been waiting for her to get better; maybe our presence would give her some energy to improve her health. But she was not better. She was getting worse and was in a critical condition.

I tell Davoud to stay outside his office and I will go and pick him up from there and we could go to the hospital together; perhaps we would waste less time this way.

There is rain coming down in sheets; it washes the hair.

In Mazandaran there is a special name for it: hair wash!

I am tired of driving. As soon as he sees me he takes over the driving and says: “Move away… I’ll take the wheel, you are not a driver now…”

I have laid Pomegranate on the back seat. As I move to the other seat I reach for Pomegranate and bring her to the front and press her against my chest. I close my tired wet eyelids and lean my head against Pomegranate’s head. Julio’s voice is coming through the speakers in the car. Davoud looks at me with concern and says:

Who did you talk to?

I talked to Maryam. She said your uncle is going crazy with sorrow. He has aged twenty years in the past two to three week. His hair is no longer black… It’s gone completely white. He is crying all the time, that big man.

She said she too hasn’t eaten anything for a couple of days.

Well, they are the father and mother. We have to see what the doctors say. As you know, they always make things look worse than they really are.

Sure, father, mother, child… This eternal triangle.

Now it was Homayoun Shajarian who is singing: “You didn’t say how beautiful the moon is tonight; You didn’t see how anxious and impatient my soul is for sorrow…”

I can’t stop crying. I don’t want Davoud to see me. He caresses my hair. I don’t move. I remember her saying I want my hair to be like yours. This, it seemed, was her only wish.

The highway is as usual packed with cars. It is just our luck that today the traffic is at a standstill. A little farther ahead there are police cars, a fire engine and an ambulance.

There is an accident and the rain is washing the blood from the tarmac. The bodies are covered with white sheets.

When we get to the hospital car park I look for other members of the family’s cars. I don’t see any of them and this is a good sign for it means nothing bad has happened and uncle is unduly worried. But Davoud immediately reminds me that the hospital has another entrance.

He is walking a few steps ahead of me; his face is red and he is nervous. He takes hold of my hand to go in together.

His hands are shaking. When we enter we find all the family there. Uncle and Maryam are standing by the bed. Uncle is bending over the bed and Maryam is kneeling. They have allowed her parents to be by her side for a few minutes.

From behind the glass I wave and then hold Pomegranate up so she can see it. She manages a faint smile.

They are injecting her and her eyelids look to be getting heavier and heavier.

I don’t know what I should do now. In fact, I don’t know what one can do in these circumstances. The place in filled with silence. It seems as if there is not a single sound from anywhere in the hospital, or if there is I can’t hear it. It feels like it was here, that moment when I caught the corner of mum’s chador hearing the woman screaming and saying: “I don’t want… I don’t want…”

I put my head between my hands to stop hearing the voices of the past. Even tears have lost their way. I say involuntarily: “Despair from the jealous eyes of destiny… Your arched eyebrows… Your Pomegranate… I am broken and in despair…” I am holding Pomegranate with both hands against my chest. It is evening now and a little away from me the women members of the family have gathered and are sobbing.

Maryam and uncle come out of the room together. Maryam is stooping as she walks; she seems to be carrying the world’s burden on her shoulders. Uncle looks many years older and is walking with difficulty. He helps Maryam onto a chair and he leans against the wall.

I go to Maryam and kneel in front of her. She takes Pomegranate from me. I put my head on her lap and feel the shaking of her legs. She is shaking all over. I say: “Why are you quiet? Cry, cry a little, shout a little, scream; you shouldn’t be so quiet now; it is your right to scream.”

She screams and from the deepest part of her heart she wails. Wailing, wailing, wailing…

Sepideh Zamani

Sepideh Zamani was born in October of 1973 in Iran, Mazandaran in the city Shahi. Zamani spent many years establishing herself as a short story writer amongst interested readers. After years of writing, she decided to gather and publish her written works. Her first series of short stories, Barbuda, was published in Iran. Zamani’s most recent novel, Ouroboros, is the second of her published works. Ouroboros, meaning a symbol of cycle, tells the story of what should have been an eternity of love and happiness ever after, turning, instead, into a cycle of pain and misery. Zamani has a number of other short stories, varying in genre. Her second collection, “Sleeping in a Dark Cave,“ is focused on illness and death during exile. Her third short story collection, “Women Looking at the Sky“ revolves around the topic of women’s rights. She graduated from Law school in 1999 and left Iran a year later. Zamani has lived in Washington DC since 2000.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!