By

Omowunmi Osuolale

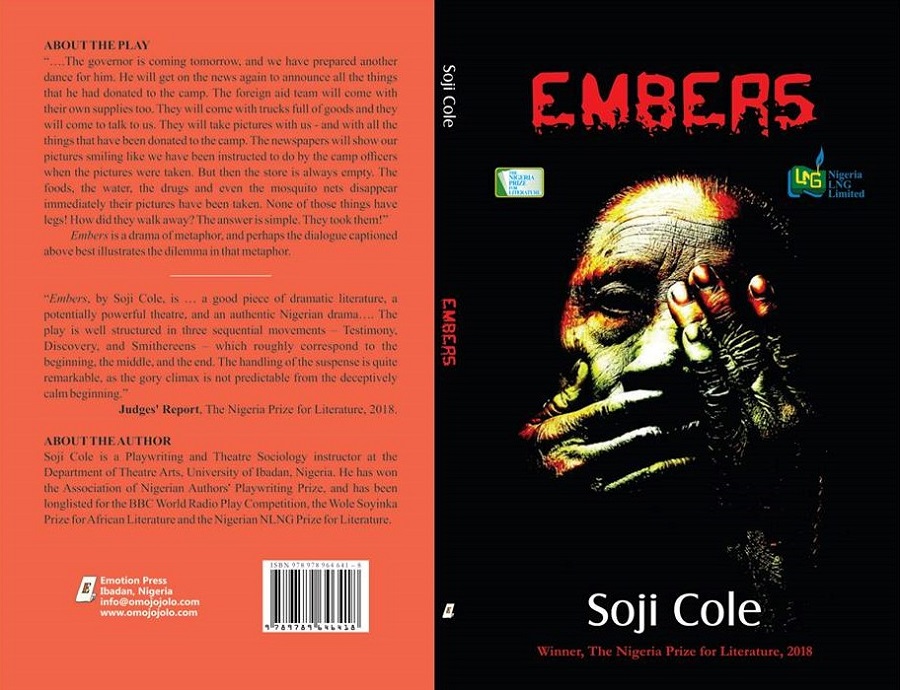

The drama book, Embers, by Soji Cole, is a brilliant yardstick to explore the given tendency that a writer is as good as how he has been able to use language to tell stories and capture the attention of the audience.

It is observed by V.U. Longe and Ogo A Ofuani (1996) that language is not meant to serve merely as a decoration in literature but should be deployed by writers to serve thematic and aesthetic purposes. According to V.U. Longe and Ogo A Ofuani (1996) the understanding of modern literature is often impeded by the conscious adoption of the technique of ambiguity by modern writers, not for sadistic purpose of creating complexity and incomprehension, but because of the positive values of the device which is the capacity to enrich a literary work with multiple meanings and several valid interpretations. This attribute is considered as one of the unacknowledged advantages of the often criticised ambiguous works of Wole Soyinka.

A similar point on the beautiful use of language is made by the Irish poet and playwright, William Butler Yeats, in his book The Autobiography of William Butler Yeats:” We should write out our own thoughts in as nearly as possible the language we thought them in, as though in a letter to an intimate friend.”(p.68). Yeats further states how the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw ‘became the most formidable man’ among modern writers through the creative use of language in his drama: “For the first few minutes Arms and the Man is crude melodrama and then just when the audience are thinking how crude it is, it turns into excellent farce.”(p.187).

Embers illustrates the ongoing problems of terrorist attacks and the paradox of their long-term presence in our community through beautiful dialogues, traditional method of storytelling, local dialect, suspense, songs and dances. In the drama book, we are introduced to the experience of the internally displaced people, especially the female victims of the Boko Haram terror group now in a government makeshift camp in the northern part of Nigeria. Rather than causing the Boko Haram terror group to crumble, it is the government’s actions that serve as the sparks that add to it. We would think it would be just the opposite. One can rightly observe that the eventual outpouring of anger and resentment of the female suicide bombers in the play, as seen in Idayat, stem from the growing moral decadence of the political leaders and the military who are meant to stand up to care for the displaced people.

IDAYAT: Everything will be fine in the end. But the end is now.

TALATU (with daunting suspicion): How do you mean? (IDAYAT opens up her veil. Her body is wound up with different set of bombs and fuses. TALATU’s face changes from momentary fright to cold glare).

TALATU: I…,I don’t understand…

IDAYAT: Yes. Goggo. There are so many things that you don’t understand. Some of us came into the camp for a mission, disguising as displaced people. We are actually emissaries working with Boko Haram. Memunah was part of us. There are still others in this camp yet unknown to many. Even some soldiers in this camp are part of us. I told you about Qudus. My first love. I found him in the forest of Sambisa. He taught me new things.

(TALATU is dazed. She steadies on the tent doorpost and plants herself on the stone seat. She is in complete disarray).

IDAYAT: He taught me that the real Boko Harams are here and not in the forest. Those you call Boko Harams are a group of young agitated men and women, but those who empower and use them are here right now-the politicians! They are the ones who snuff lives out of the people they are supposed to lead. (pp.92-93).

We cannot read the play without coming face-to-face with the reality of depression, political misappropriation and religious extremism, child marriage, rape, homelessness, gender inequality in the playwright’s use of language. Women and children are becoming the victims of terrorist indoctrination and human rights violation. Extra judicial killings are illustrated in the play.

ATAI: The horrors that I saw in five days were more frightful than the fiercest things I saw in Sambisa forest. The soldiers slaughtered any man that passed by the village. They didn’t even wait to ask questions. Some men who escaped the destruction of the Boko Haram boys were returning to Gali to see what can be salvaged. They were all killed by the soldiers. Even when I told them that I knew a man they captured, they threatened to kill me too. (p.58).

Soji Cole sheds new light on the fight against the Boko Haram terror group and how it has become really complex to deal with. Many of the female characters portrayed in Embers are embittered. We see this attribute in Memunah, Atai and Idayat.

As victims of both the Boko Haram terror group and Human rights violation in the government makeshift camp, the female characters in the play parade around as innocent young girls, helpless, and weak. However, it is later revealed that many of them have been hiding their true identity and affiliation with the terrorist group. The indoctrination has gone really deep and complex. Talatu, a fellow victim, who has become a trusted counsellor and mother figure for the young girls in the camp steps in to win back their hearts and make them to see the destructive consequences of their decisions to be suicide bombers with no success. They are nauseated by the paradox within the government. We cannot miss the mastery of expression in how Soji Cole outlines the stage directions in his play, Embers.

Soji Cole

Soji Cole teaches Playwriting and Theatre Sociology at the Department of Theatre Arts, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. He is the winner of the 2018 Nigeria Prize for Literature.

Omowunmi Osuolale

Omowunmi Osuolale is a prolific writer. She is currently a student in the Department of Theatre Arts, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

References

Soji Cole, Embers (Emotion Press, Ibadan, 2018)

V.U. Longe and Ogo A.Ofuani, English Language and Communication (Nigerian Educational Research Association, Benin City, 1996)

William Butler Yeats, The Autobiography of William Butler Yeats(Macmillan, New York, 1965)

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!