An extract from forthcoming crime novel ‘Night Wolves’

By

Celestine Chimummunefenwuanya

I

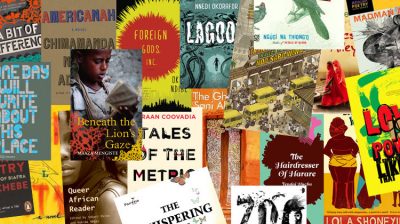

Chinagorom has been reading a lot of novels lately, although it had barely been by cheap contacts, not by expensive choices. If money had been available in his family he would have been a bit selective, and if he had gotten this choice for certain and he pretty knew it, his friends, Ochiabuto, Zebrudiah and Jedi knew it all, the drive to read and devour a pyramid of prose books lingered there in his imperceptible veins, he would read crinkles of powerful, trending African novels in one go. He loved and loathed American novels in some ways, when they were stereotyped fictions spurned around the hub of wars and dune of romances. The intricacy of expression and all the stuff that make you want to collapse because every sentence rocks your head. African fiction makes him feel an African, and at home with a taunting pride. The grace of simplicity, the feel of concern for the low-learned African readers yet not compromising in the undeviating conveyance of the points of pressing themes, the life-changing themes and all that so packaged in African imaginations, he believed, would grant him the energy to trill outside the limit of his African voice as soon as he read them one day.

That was Chinagorom. He loved African novels; Chimmamanda Ngozi Adiichie’s ‘Half of the Yellow Sun’, Helon Habila’s ‘Waiting For An Angel’,Chika Unigwe’s ‘On The Black Sisters’ Street’,Sefi Atta’s ‘Everything Good Will Come’. He wished to read these African novels, having read their reviews in Kelechi’s browsing Techno phone, but what cheaply came his way, though expensive, were foreign, American novels.

Chinagorom was choiceless, money wasn’t available with his family, the only source of novels he read were a few ragged stores opposite Effium slaughter house called ‘ozo gbogorogbogoro’. Here, it was the place where rusted and corroded farm paraphernalias and old home utensils, broken furniture, burnt home appliances; wireless ruptured televisions, shattered radios, knocked speakers, frizzled American toys picked in Nsukka dustbins, pungent Italian brogues shoes picked in Enugu slums, dog-eared host of books and ripples of scrunched magazine cracks packed still from Enugu dustbins were assembled for cheap reselling.

As soon as the school dismissed in the afternoon Chinagorom would hang his threadbare Capri school bag and walk for Christy cafe and going, he endeavored to meticulously stuff his lunch fee in the depth of his cyan-pink trousers’ left pocket; of course it’s his access into the dirty cafe of luxurious novels from the best beautiful minds in the world. From Gloucestershire, Caroline Harvey or Joanna Trallope. From Manchester, Kennebunkport, Kenneth Roberts and from England, Winston Graham. Sloan Wilson from Norwalk, Connecticut. From South Australia, Babara Jeferis. Elizabeth Spencer and Eric Walters, Diana Galbadon, James Patterson and Margret Miller from America.

Definitely, they were the objects that drove him there; they were the reason de tar he’d not spend his dirty notes on snacks or beverages, on okpa,akpe and Iyamangoro. They were the reason he could think and speak with the best furnished English, with flowing intricate intonations in Mayflower Academy Effium. When he got to Christy store he would wave his Nigerian currency notes, like a crumpled wand across her face to inform her he has come to buy books and not to play and browse through books with empty pockets, without buying. Just the habit of his school boys to this poverty-hacked seller that woke a monster in his head and made his head tick.

Christy knew Chinagorom well. He wasn’t one of those boys, those science boys, Caleb, Ozoigbondu and Okpoto who disliked novels and would indicate their hatred by havazardly wagging their hands on them, telling the woman to her face how they felt nauseous for the grubby art books, for her stinking wares. She knew him well. He was someone that could be trusted to buy five to six foreign tattered novels he could lay his eyes on.

Seeing him, Christy would smile, nod her head and informed him with a sharp feminine grunt she had seen him and he should go ahead and search and ransack the dunghills of dirty books, swollen graves upon graves of murky papers. When Chinagorom picked his choice or the few novels he contacted she would say ‘let me see’, that’s after he flailed his selections to her face. Like an Effium hot breeze rustled to her face, she would close her eyes and grin like she loved him for loving books and wished he was her son or that his love for books reminded her of a cryptic past; that perhaps involved an intelligent child she once had that died prematurely.

He would go over the hill of filth with his ungloved fingers, digging to and fro for novels he could contact, see and touch. He’d wondered the sort of individuals who flung out these powerful books without caring to check their costs and values. But once, he queried Christy just on this and after a sprained minute of tranquility, she claimed they never picked those things in dustbins; ‘we bought them, we never picked them’ that’s what she said, perhaps she agreed saying the real fact could deflate the prices of her ostentatious wares, ‘ostentatious’ that’s the best paradoxical adjective she like other sellers used to nomenclate the gbogorogbogoro business. They knew the truth, about how they bent and picked them in New Heaven dustbins, Milliki Hills open-vats of reek rags, and Nineth Mine grease-framed silos of broken porcelain plates, and do not tell them the truth pertaining their wares were ‘picked goods’. ‘They could whoop or whistle you from their stores. If you happened to have seen Christy somewhere around Enugu doing her picking, and you interrogated her, Christy, because she can’t deny you seeing her, would say, at least to loan her business some dignity, few American ladies, few Lebanese men from Washington D.C, few cowboys from New York City who lived for temporal missions in Enugu flung them out to the dustbins and we packed them down to some other rural villages in Enugu, then down here in Effium, Ebonyi for cheap reselling.

Often it yanked and preened furiously at his tight skin that the people he belonged went out there to pick wastes in Enugu dustbins and came to suffocate them with the putrescent smell here. Once he tried clearing his head with questions on why Christy stooped so low, why some of the Ebonyi women stoop so low to pick from dustbins in Enugu, and Christy had laughingly said ‘my son, not the Ebonyians alone who picked things, and it’s not in Enugu alone the white people lived who discarded wastes’. White people sojourning in Waterworks roads, the Paramilitary boulevard, Gunning roads, Salt spring hotel, Crunchies resturant, Osborn Lapam Hotel, Mr. Biggs, and Ebonyi hotel also cast out good resaleable stuff, and peasants from here like us, and he would say ‘tufiakwa minus me’, peasants from Enugu, from Abia,from Anambara, from some other states in Nigeria would rout through the Unity square to Paramilitary layout for brisk picks.

He looked straight to her evasive, poverty-discolored eyes with butter-like shining blobs filling the edges of the irises and inhaled a heavy breath like a gulp, at least a bit relaxed that his state wasn’t the only state in Nigeria where the rural women weren’t employed or loaned to do short scale businesses, so they go to pick dirty things on the dunghills made available by the temporal white men. And to the best of his knowledge Effium rural women were acutely abandoned by the state and federal government. They rotted and pined away in poverty just like his mother who had to fetch firewood in Okporo forest before she’d wear ekwa okirika.

His picking is by contact, any novel he touched he picked. When Chinagorom picked the few American fictions on romance and race he would pay Christy. The novels, no matter hefty, have no fixed prices as in the city book stores, bargaining determined the selling price and the price he got these American perspirations often made him wonder if writing is worth going for; and the qualms the authors traversed; some authors romped through hot and cold suburbs, leaned on subways, gapping about for vital clues, from boroughs to boroughs, thorny, hilly countryside for their research and after they cleverly packaged their sweat you bought them with a ‘meager sum’. But a thought gave him solace, as he grew older he understood those who discarded them to the dustbin paid for them first in the book shops and stores. The authors have not lost anyway.

He’d stretch out a furrowed fifty naira note for two American and New York Times bestselling novels to the woman, and the yellow-toothed Christy, sweaty and apparently bland from the hot Effium sun, would giggle and say ‘haba, why not add at least twenty naira’. He knew she was right. Been a growing writer fantasizing to be a bestseller someday. She was unarguably right because the multiplication of what he gave to her to a thousand wasn’t worth the American sweat. Yet he was helpless and ashamed to be issuing such amounts for the hefty novels. He was poor, his family could not get him money to pay exorbitantly as he wished for the novels, and because he spent his snack fee and nothing else in his pocket to add he’d say ‘Madam, I’ve got no other thing to put, do get this from me please. I’m a student’. And the weedy yet sentient woman, Christy would momentarily glower and sulk, then snigger and say ‘you are always a student you big head’ and collect the note from him.

With hunger smoldering in his stomach he would sometimes belch hysterically into Enwemiri-Isuochi untarred, pothole-filled narrow road. It’s a natural thing when you have a novel of a great novelist, a bestseller, even an American bestseller like James Patterson in your fingers when you never expected it for lack of funds, if peradventure, you got it on the highway you’d read it without minding the hooting lorries and blaring motorcycles. I lied? In Nigeria it’s a fact, it’s a verity in Ebonyi. Ebonyians love prose books to die.

He’d scuttle through Ikpoki junction, the way of cars, reading the novels he got ignoring the whooping, tootling voices of the massive gwongworos, Honking bajaj, withered kymco and crooked carter okadas rolling in from the city’s market garage and Okporo suburbs, and all those quaking yells and elusive screams you heard from the nervous people by the side of the road when cars come at you and you weren’t aware.

Sometimes, he reads his novels under trees. When he reads the novels he got new under trees with hunger-ridden stomach it isn’t a qualm, it’s a therapy or at least an escape from the bleaching quandary of family poverty and the cerebral palsy that entwined his sister, Chinelo. He’d close the novel and jump into the pedestrians after a tingling nudge, in the nape of his neck with a furious blow on his left behind from one of the Ikpoki kerosene sellers, always a batch of growing boys or an Effium toothless task collector that had yelled much. He’d get into the Effium divisional police headquarters, just along the gleaming, tar-encrusted Overbridge expressway, there in the heart of the station stood a tall and short mango trees with pink-blue ruggedious foliages. He’d greet the policemen chirruping and discussing the recent crime in Effium, then jumped into double Iroko planks set underneath the foliages and got riveted in the exhilarating prose.

Once in the tree, and it was more the reason he loathed American romance fictions, although he might be synedochical, he read a romance fiction that almost made him wet his pants, the novel’s name was’ Romancing the Stone’ by a female American writer. It was the chapter of those romance things, what he was made of, you should know it, stood out stony, he was ashamed and he prayed nobody shout at him to stand up, if that should happen he’d be humiliated, and this erotic urge that grasped him in his under made him dislike American fictions with a passion, not every fiction, not anything like George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’ and his ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’, not anything like Eric Walter’s ‘Safe as Houses’, not anything like Charles Dickens’ ‘The Tale of Two Cities’ nor Caroline Harvey’s ‘The City of Gem’, despite the fact he was not sure they were American writers and books.

II

And now, in the ebb of November, having packed many novels from these dirty stores where books wouldn’t seize for a minute to be surplus and cheap to posses, Chinagorom has been reading many novels lately; Pat Conroy’s ‘The Great Santini and the Prince of Tides’, James Stewart’s ‘Star’, Magret Miller’s ‘Beyond Here are Monsters’ and Anita David’s ‘Green Fingers and Grit’. He has been developing lately. He has been painting a new big picture. He has given himself a big cut. He has been placing or seeing with the prism of imagination his feet set on the topmost horizon of literary fulfillment. He’s been building a flair to write a novel he’d call his own. He’s been dreaming in the daylight. He’s been setting himself up high, he’s peaked the height of the dream to write his own novel. He’s been building a little light, the light to be an acclaimed novelist, not just a novelist, a bestseller like Chimmamanda Ngozi Adiichie, like Helon Habila, like Sefi Atta, like Chinua Achebe, like any great African writer recognized worldwide; to write a novel worth publishing, known all over Nigeria like ‘Waiting for an Angel’, ‘Purple Hibiscus’, ‘Half of the Yellow Sun’, ‘God of Small Things’, ‘Things Fall Apart’, all over Ebonyi like Satan and Shaitans.

Publishers spread about Abakaliki and they could publish a good novel, Kwuzie told him, a TV presenter announced it on Ebbc One midnight and now outside his father’s house he was planning to write a novel and getting it published would be an uppermost yarn. Three weeks later he wrote a delicious fiction he called ‘Flames’. He reviewed it every night. Once, in class he gave the manuscript to Soromtochukwu, the most lovely and eloquent in the whole of Mayflower High School. That harmmatan morning Soromtochukwu stood in front of the class, the curios prone-to-rebuff boys and girls. After she beautifully and succinctly pronounced the slapping phrases, sharp anecdotes and touching epigrams in the first two chapters the strong-headed classmates gawked at her, then at him. He loved modesty and despite laughter flowing in his mouth naturally he kept a blank face so he was not regarded a proud peacock. Sabina, the science rep mewed incredulously like she was some sort of bemused cat, like the seagull. The long-mouth female science students piped nervously like they were entrapped nightingales and said ‘No you never wrote it Chinagorom, at your age? Sixteen? SSS 3? An Ebonyian? From Effium? A Mayflower student? Impossible! You plagiarized a notable novelist. He tried to convince them it was a talent, that he never plagiarized any novelist’s work but they were too overwhelmed to listen to him. Their awe motivated him. They respected him and it appended more sinew to the senior prefect he was. Their love for the story drove him to swear he must publish the ‘Flames’. After all, Oscar Wilde said it, you are a novelist if five brilliant brains could marvel at your creation and no novel is bad.

Every day, his father was poor. Everyday his mother was penniless, everyday he watched his sister travail under the shackles of cerebral palsy. Every day he watched his family sink in the cesspool of poverty. There wasn’t any food in the house, and the day he talked to her mother, the clatterer, because she bickered round the house whenever her husband, his father, said he had a bad day in his job and would not be able to provide money for food, she whispered ‘noful?’ what is noful’. He said ‘novel, not noful mama’ he dared not call her mummy because she hated it and that’s because Obiageri once told her one morning, a mummy is a wrapped corpse. That morning she yelled and forever banned him from calling her that ‘thing’. His mother then said ‘Ehen, and then’ and Chinagorom said I want to publish it. She said ‘kpoflish? Hern, ngwanu, kpoflish nu’. He looked to her eyes and saw a monstrous robot of impecuniosities clutching a sharp sabre bearing at him, warning him, and telling him not to mention money or he’d sever his skull. He saw poverty in her eyes glowing like hell. And it swallowed all he wished to say.

Every night, he’d roll on his mat. Daydreaming. Dreaming where his ‘Flames’ won the Commonwealth prize like ‘Purple Hibiscus’ and won the Orange prize like ‘Half of the Yellow Sun’. Dreaming where he hugged Chimmamanda Ngozi Adiichie. He would delightedly wake up to see nothing but his mat and the crackled mud-wall and on the wall sometimes would be a contingent of crawling gecko and a brigade of staring, silent lizards usually on the edges and tops of it, and on the plastered floor the buzzing mosquitoes hovered in the air and perched.

Sometimes at twilight and midnight, humming bees from the cashew tree in the backyard fluffed in through the crevices beside the shaking window louvers to slap his face and he’d exchange hot blows with the pregnant buzzing, humming bees. And he’d hiss. ‘The worst malady is to have a story to tell and you can’t get it published, you become sick and miserable’ He told Afusa one evening. And added ‘you felt it was over, you grow thin, despondent and damp. And if care wasn’t handled you might go mad’.

One late December evening, the breeze swatted around the glowing bulbs outside the house and sealed the verandah with deep-yellow hues; Chinagorom’s father was a bit learned. He spoke ‘complicated grammar’ and even now he thought big grammar without money is madness. Outside the house, he sat underneath the shimmering bulb and read an issue of Ebonyi Voice. He soliloquized ‘Ucha and Elechi war. Big war. Let’s see who wins now they are in the Federal High Court’. He trudged him from the back because he sat in a bunk bed.

He bumped up and yelled. ‘you clattering bagatelle, you, mannerless, rancid baguette. Obdurate Narwal! In his little mind he was yelling ‘big grammar can’t solve the matters on theground, money does. It can’t cure Chinelo’s cerebral palsy, money does.

“What is it” his father grunted finally

“I need a little money.”

“The batch I plucked from my buca cavity?”

“No sir, I want to type my novel.”

“Novel?, are you mad? Your mates think of reading to make their SSCE exams and you stand here to talk rubbish. You are demented and convincingly quadriplegic. A dim-witted, hypochondriac inebriety.”

“I understand Papa, just five thousand naira to get it typed then I will take it to a publisher in Abakaliki.”

“I ultimately realized you are totally anathema. I have Five thousand! And your sister decayed in the grip of that thing in there. You are a lifeless desert luna moth, in fact your presence suffuses typhoid, decamp before I have a heart attack.”

He never blamed his father, he knew it, he wasn’t the one talking. It was poverty that spoke. Mrs. Adaebonyi, the literature auntie used to say ‘when you asked a poor man for money. He’d cry, then shout at you, please when these occur take it, it was poverty that shouted not him’.

He was right they’ve got no food in the house, his father’s business had been failing, her mother’s fire-wood business collapsing too because women now got raped to death in the Okporo forest. His exam fees stood out there like a stubborn mountain and he talked about novels. He left his presence and almost wept. A few days later, before he was chased out of school for not paying the second term fee, Soromtochukwu, the Enugu classmate advised him to show the novel to the Mayflower Principal and here was the dialogue that ensued between them. The principal, a plumb Egba-man, heavily mustached from Abeokuta.

“Good morning sir” Chinagorom said.

“Chinagorom, how are you?”

“Am fine sir.”

“Am I safe Sp?”

“ Very safe sir.”

“How may I help you?”

“Sir, I have a novel, it’s good. It’s worth publishing. It’s awesome. It’s special. Its compulsive.”

“Really?”

“Yes sir.”

“You have the funds?”

“No sir. That’s why am here.”

“How?

“Publish…yes, i..i..i need to publish…”

“I get where you are going to. But I must tell you you are wasting your time and energy. Go to university before you write.”

“Sir, but Ben Okiri was published in the age of seventeen.”

“I’ve got no help I could offer you dear, and if at all, you still owe the school.”

“Just help me publish this novel, I’d pay and add jara.”

“Now I think you are mad. Piss off right away. Leave my office.”

And he wept. He wept because in his tiny mind, taking the novel manuscript to a publisher, if he would get one at all, would fetch a lot of money to change his family. To carry Chinelo to hospital for her maligning cerebral palsy surgery. To pay for his school fees and final exams. To get her mother a good shop and store crammed with food in the most expensive part of Nwafia market rather than watch her comb the evil Okporo forest for firewood. To wear chic denim jeans. Refurbish his father’s crackling hut of crawling filigreed geckos and staring, nodding lizards, to change his father’s bricklaying business. But his effort to get five thousand naira was fucked up. And he felt this warranted the principal to send him out of school the following week for his debts.

III

He now stayed at home. Every day the poverty in the family interlaced his mind so his thinking was preposterous and heavily ludicrous. Every day he wept for the cough-like groans of her baby sister from the inside, from the preening impound of cerebral palsy. Every day he wept watching mother tearfully axe on a log of melina wood and wept more in the market when people rejected mother’s firewood because it wasn’t dry. Father was a bricklayer. And he wept each time he wept into the compound with his clean trowel to tell the wife and children he wasn’t picked for work by anyone.

One afternoon, his father told him he’d start to sell sachets of pure water to support the family. Not even to publish his novel, that was a smoldering fascination. And how he loathed this business for it’s underrating aura. In Effium, in Mayflower Academy it was, and he was aware, the sons and daughters from poor, not just poor, very poor families hawked sachets of pure water in ndebo market. His rationale for wanting to reject the idea was the dignity of his ‘Spship’. But after many sleepless nights of contemplation and consideration that he was indeed from a poor family he bought a bucket for the reductive, cheap thing. And he felt he’d save enough money from there to secretly type his manuscript.

Daily, he strode purposelessly in the Effium sun. In nwafia market. Inikiri benard market. Nwekendiagu market, from new market to nkwo jaki. Every day he sold sachets of pure water but nothing was coming out of it. He’d would under the burden of heavy loads on the scalp of his head roam around Effium market squealing ‘gonu mmiri juru oyi’ ‘o Aqua Rapha Mbaka’. He’d squeal from Effium garage to Ikpoki junction, the rendezvous of smoking derelicts and loose scalywags. From there to Overbrige.

Two events took place that made him most miserable. He shared his pure water-selling between picking and staying to read novels he picked from ozogbogorogbogoro, the dirty stores. That’s the name of the dirty stores that provided him with a lot of American bestsellers. And racks of New York magazines. With very cheap prices. And the name meant the cafes of tins. It was where he first saw the light. Where he picked the books that inspired him to dream of becoming a writer. And the magic behind the imagination of ‘Flames’ store. The Cafes of Tins.

Almost every day he’d drop his bucket of sachet water at a corner of Christy’s café and devour chapters upon chapters of interesting fiction he could touch or see. Reading was his natural thing and he did it with an unfailing leverage. Once, an old aru man howled at him ‘this boy your pure satchet water is getting warm, go and sell it and stop reading for now’. He got up and Christy nervously said ‘I don tell am oo’. Another Ezza man, a regular customer to Christy’s café said ‘I too warned him to always finish his water before coming to stoop and pick here’. He shrugged and retied his scattered oja and hurried away, quoting the vital, salient sharp phrases and epigrams he picked for the chapters he was able to read in his head and heart. Imagining what happened to the hero he encountered he prayed he sold everything in time so he could continue from where he stopped at home after he bought them deducting from his gain. But one day, the sun burned heavily. On passing with his heavyweight bucket of pure water filled to the brim his eyes cut the well-designed cover of a very huge novel, ‘The Drums of Autumn’ by Diana Galbadon. Unconsciously, he placed his bucket full of water on the edge of a tall jagged jet stone and dashed out for it. He had gotten over the acknowledgement and prologue and just commenced with the first line of chapter one that read ‘ I heard the drums long before they came in sight. The beating…..’ and he heard a heavy crash on the gritty ground. It took him minutes to return back from the long voyage the novel quickly carried him on, and saw his shattered bucket and broken sachets of pure water. Twelve sachets spilled into the gritty dust, wasted away.

He wept hard. ‘My father would kill me, how do I get a new bucket. How do we feed today?’ he worried. Christy looked at him with an infectious sense of empathy. She was poor and from the look in her tearful eyes if she had gotten much she’d have paid for the loss. Yet, she did him a favour, and wasn’t aware of the cost of it. She gave him the hefty novel for free. Partly, he was happy for getting Diana Galbadon’s ‘Drums of the Autumn’ for free, and he was partly embittered for his carelessness, for his broken bucket.

Back home that evening his father knelt him down. He did nwewo jump and slurped era nwanyi Asaba before flogging him with a hard whip. The one he used during the Nigeria-Biafran war to draw welts on the skin of a captured Nigerian soldier in Abagana and on the neck of a Hausa Nigerian Army on the outskirts of Sabongari. His mother wept that night and mopped his welt-clustered back with hot water. His father insisted he would sleep without food after it wasn’t available in the family-contained quantity. And he slept with an empty stomach that night. But before he slept he read five chapters of the ‘Drums of the Autumn’. And he dreamt about the criminals hung to death in the novel, of the scent of the ancient Scotland the novel revolved.

A few days later he bought another bucket and was selling again, but this time he was careful, his infatuation or whatever for novels was control against haywire.

And again, one sunny afternoon, what he never expected occurred. The thing he dreaded. He’d dodged from the view of his classmates when it was two o’clock. He loved the rigmarole within the market and dared not go outside the uwobia road so his classmates wouldn’t see him as they walked home from school. They would mock him and laugh at an intelligent senior prefect from a very poor family that could not afford his school fees. That afternoon, selling was dull and his water almost went hot in his bucket. It was harmattan and his lips had dried up and properly swept off moisturizing fluids by the harmattan dusty breeze. He was miserable that market day. The dream to get published. The thought of selling out a warm, or going-hot sachet of water tumbled in his skull until he was trekking unconsciously through the uwobia road towards ikpoki junction. The road he had averted. Screaming ‘go mmiri juru oyi’. And unexpectedly from his behind an explosion of laughter banged hard against his tiny spine. He checked and saw a host of giggling science classmates, except Ofodile, twittering and yelping, sqwuaking and snarling words of demeaning mockery just at him. He was ashamed of himself. He ducked through cars and soon was inside the market, his hiding place. There he wept and mocked the poverty that churned his family that adhered Effium like a giant luna moth in the silver webs of lack.

IV

A week before the exam commenced Chinagorom got new, miserable work in the city’s rice mill. He woke up before dawn and swallowed cold utara and set out for work. A miserable work. There in the rice mill. Lots of children from poverty-ridden families struggled over who would turn the fairly-processed bags of rice into the thrashing machine. If you were lucky enough, and the luck was determined by your ability to wake up early, to turn bags of rice into the machine, you go home with cups of rice equivalent to the number of gigantic bags you upturned. If you turned five bags in a day, a hard fit that consumed the whole day, with hunger and aching skin, you would stagger home and sometimes weep with the five cups equivalent to the five bags. ‘Isn’t that a miserable work? And it is what a Nigerian child must do every day to leave’ he once told his co-laborer. What suffering of a job. As the children pour the cereals into the machine, the rice chaffs bite and make the skin tingle. Peradventure you came late you’d have to climb into the mountain of the rice sun-dust to puff out a hill of it with amatakele before you could get a grit-filled cup of white-purple rice.

Often, he was lucky he came earlier and went home with five or six cups of rice late in the night. Sometimes he would be unable to get up from the stress of a hard work. He would climb straight into the mountainous sun-dust that was the first thing you see when you enter Effium from ezzamgbo or iziogo and used his Amatankele to trash out the dusts. From morning to night he could go home with two to three cups of rice with hunger gnawing his intestine. And often he pitied some city children and old women having no dream like him, remaining in the miserable, soul-exhausting work till death.

One morning he busily poured a bucket of rice into the funnel of a warbling machine. A little girl was at the back of the machine, cropping out the dust. What happened he can’t detail but all he vividly remembered was the girl’s arm was drawn into the rolling pulley, a crackling sound, then blood sputtered about the ceiling and the operator switched off the engine. And the hungry, miserable girl of eight laid there with a broken arm in the lumpy pool of deep-red blood. This wasn’t the first time this horror would occur in Effium rice mill; the girl’s broken limb dangled in her shoulder. Soon the rice owner Madam Caro, a fat ,dignified woman of about thirty-two, came from where she was called and said the helpless bleeding Chinasa should be bunched outside and ordered the operator to go ahead and grind his rice or she’d be packing her leftover bags to another mill. And said ‘I never killed her if she died. Her family who can’t provide for her was to be blamed and the work progressed. And the girl laid there unconscious and he grew empathic and thoughtful.

V

Chinagorom came to the rice mill with the novel’s manuscript. When he had no work to do, he’d supine on the payment and reread it and do some canceling and adding of words, phrases and letters. Of all the Nigerian authors he cherished and wished to become was Chimmamanda Ngozi Adiichie. He agreed you want to become a good author you loved and read every day. Her works were easy to grasp without qualms. She’s bagging awards in America. Ordinarily, for being a black African who wrote just like an African and not writing to please any American reader. Once, on an excursion visit to Sam Egwu’s poultry in Abakaliki he visited a book shop along Ojeowere Street with a few of his friends. He set his eyes on the yellow cover of a novel titled ‘Half of the Yellow Sun’; he saw the image of Genevive Nnaji in the right edge of the front cover, then a background of blasting grenades and a running family. He never took it seriously, he felt it was a Nollywood film converted to a novel or whatever. He was penniless but the pale girl selling in the shop considered his request to only browse through it then drop it. When he lifted it out of the catalogue it was sitted. He marveled, still, he never took it seriously. He marveled for its heftiness. But when his eyes picked the heavy-black names CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE and the glossy image of the dark lady with a captivating hairdo he yelled and limped up. He whined heavily and everybody busy within the shop stopped and fixed their eyes on him. Silence swallowed the shop. He said ‘Yes! Yes! She’s great and the book keeper asked him ‘who?’ and he said ‘she’s great! She’s making us proud. In the UK, America and in London; she looked at him again and asked ‘who now?’ and he said ‘CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE’ she’s written another novel. She laughed and said she’s written almost four novels including her award-winning debut novel, ‘Purple Hibiscus’. And she listed them. ‘Americanah’, ‘The Thing Around Your Neck’, and ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’. ‘Wow’ he yelled and his love for her increased. And his yearning to be like her deepened.

When it was time to work he would hide his treasure in his tattered poly bag and he would dream high. Getting published by Farafina, by Cassava Republic and Jacaranda.

Everyday he saved a cup of rice in a small box he kept among the stored bags of raw rice in an apartment in Mill 2. He planned to gather as much cups of rice as possible until he could realize the cups that corresponded with the money he needed to type his manuscript. So he saved cups of rice and soon the box was filled up. The day he brought out the box to sell the rice, that day his joy was endless, the fat woman, the heartless Madam Caro, swaggered out. She was the woman she worked for that evening and her rice that entered his box that evening was a cup from the five cups of rice she measured out to her after upturning five bags into the machine. Madam Caro grasped and lifted the box and started to scream ‘thief, thief, thief’. He was surprised. The rice was his. He saved it. Soon some boys loading garri bags in the garage lumbered into Mill 2 and began a mob action on him. He woke up in the police counter. A new policeman in the station walked up to him and lowered a heavy truncheon on his head ‘little thief, rice thiefer’ ‘I am innocent. The rice belongs to me. I saved it. I swear’ he said before another crash on his head and he stopped saying any more words. ‘Rice thiefer’ he yelled again and struck the bridge of his nose and he whimpered. ‘Policemen are mad! They hate excuses when you are in their web’ Ugonne his neighbor used to say. Madam Caro said he should be thrown in the cell and locked up. But the D.P.O insisted he saw him read under the mango tree every day and that he may not be a bad boy that deserved a cell, although he never said that to the woman. It was what he said after the woman left and he swore to release him if someone came for his bail.

The next day his mother came crying with a dirty cooler of maggi-less jollof rice. ‘Mama, I’m innocent’, and he fell into her fingers with his swollen cheeks and bruised forehead. And mother and son cried and cried. ‘I know you are innocent but how did you get the box of rice?’ ‘Am sorry mama, you know that novel I told you about, that I want to publish, I secretly saved a cup of rice every day for it. Mama I am sorry I didn’t tell you, it is for our own good. Am innocent mama. How’s Chinelo?’ ‘She’s there struggling and weeping as usual. And she wept more because you are here. But never mind. I trust you. You are not a thief. D.P.O has promised to release you but he said I’d pay for your bail’. And they wept because they knew the money was not there to bail him.

VI

A day later Chinagorom was at home; his mother bailed him with a borrowed five thousand naira but he paid for it with the eyes of his father the following days. One evening he was soaking garri with ashiboko on the pavement outside the house when Soromtochukwu came to greet Chinelo. After greeting her she told him she’d take him to a catholic bishop staying at ugwu-achara. She said the bishop was wealthy enough, has many connections, chats with the state governor like they were childhood friends, drinks with the president of Somalia and Tanzania. He was hysterically joyous. Hyper-thrilled that he bawled. He told his parents he’d be leaving for Abakaliki the next day to see a bishop that would publish his novel and money would come, he said optimistically as if he was certain his debut novel would be good enough to bring much money home. The next day his father woke him up. He gave him two thousand naira for transport. He was surprised. His father will never give anyone such an amount, but to him this one was different, an investment. And he was grateful his father believed in him for once. His mother wasn’t aware what the novel thing was all about, all she knew was her husband supported him and that he said he would come home with money. She added a borrowed thousand naira to his transport and him and Soromtochuwku romped in the bus for Abakaliki.

Inside the bus he couldn’t imagine it and if he could, it was impossible to believe he would be published like Chika Unigwe, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Femi Osofisan and others. He tried to imagine himself well-dressed and walking past a group of Mayflower students reading his novel and pointing at him and screaming that’s the author of this book. That’s him. He closed his eyes. And solemnly, more like a soliloquy, said ‘I will dedicate it to Chinelo, the daughter of cerebral palsy and I would take her to the hospital’. Sor watched him steadily then wept silently. His novel might not be worth publishing in the eyes of professional publishers but he needed to be published, that’s the drive. Deep in his heart he burst into a song as they dropped at Franco junction…. This little light of mine am gonna let it shine……

Soon they stood before a brown tall gate of a detached terraced house with a very tall picket fence carrying green-pink tips. He couldn’t wait to feel the coming to reality of his dream pointing him in the eyes. Even if he could wait, the elegance of the delicate mansions was a conviction of prosperity greater than the expenses publishing his novel would entail. Soromtochukwu was happy for him and he easily picked just that in her milky face. She was the only Enugu girl I cherished of all the Enugu students that came to Mayflower for their SSCE examinations. She was quick, succulent, brave, empathic and homely, and just from Nsukka. She was the girl unlike, Casandra from Ogui, Chioma from Achara Layout, Tochukwu from New Heaven, Diobi from Independent Layout and Chadikaobi from Nineth Mile, who snarled harsh words on Chioma and Casandra when they said Abakaliki people are animals and uncivilized. She disdained just like me, the Enugu ingrates who were bent on calling the Ebonyians ‘the uncivilized band of barbaric people’. She said why must my people be unnecessarily selfish and unreasonably thick and stupid. If Ebonyi is the dungeon of the dim-witted barbarians then why can’t we make our WAEC examinations there in Enugu, if, Enugu has developed beyond rival in civilization why do we jettisoned it to study in Federal Girls College Ezzamgbo, Premier Academy Effium, Mayflower Academy Effium, St. Micheal Ezzamgbo, St. Peters Abakaliki, Immaculate Secondary School Effium, Royal college Ezzamgbo, Twelve Apostles Abakaliki, all in Ebonyi state.

Those Enugu boys and girls, men and women that downrated and belittled Ebonyi just because they were from Enugu are mad and uncivilized – orientation is civilization, not language. Enugu people have travelled to Hong Kong to Washington DC, to New Zealand to America, to Britain, to Japan, to Thailand. And who in Ebonyi state hasn’t done just that, those foreign places are the points of orientation that enhanced civilization. Everybody is equal she said. And Chinagorom said what makes them puff like frogs. What’s too special in Enugu rare in Ebonyi? What’s too special about the few he’d seen so far? What’s so special with the state that some people, prone to division, vulnerable to segregation, pimple-popping, slack-jawed, gum-snapping bunch of belching inebriates, savage little cretins dare call Ebonyi people the uncivilized and rough-edged vestigial of bruised history, nonsense, fie fie!

Soromtochukwu’s knock on the gate wasn’t wild but humble. It should be humble, a man without shoes must humbly walk in the dale of thorns. And a very dark man with comic zaggy marks dropping from his ears to his bulgy cheeks, so bulgy that you assumed he was chomping and gnawing a heavy gworo in his mouth from the way he bobbed his head in the filigreed morning sunlight and scrunched his face. And let his lips squid from perhaps a heavy intake of kpanshaga, one could be sure the stuff in his mouth was bitter and nasty. He’s a Hausa man, they were sure from the oversize cum overlong caftan he wore. ‘Kachikwo, kwu you de look kwo?

In Chinagorom’s mind he was laughing and asking himself ‘is this Hausa man toothless that he’d speak like a stupid baboon?’ Hausa people are intelligent like Labram Maku, the Nigerian Minister of Information whose sonorous voice, fluency and intonation had stirred him to dream his gonna study mass communication. But this one, he was a shame to a Nigerian ethnic group that ruled Nigeria for years. He hid his laughter in his tongue but it struggled out of his nose, lips and cheeks. Finally he burst into a huge laughter but not for the Hausa man. When you expected a million naira you never worked for in Nigeria, and a little thing that could make you laugh comes your way, you’d laugh and definitely laugh like a mad man. He laughed with a drive. With expectation. Soromtochukwu went psychological. She understood he wasn’t laughing at the gauche and tacky accent of a Hausa man that spoke like a good-for nothing ne’er-do-well of a gullible wrench unlocked from the cave of derision. She knew he laughed for an expectation of his dream rolling away from a mere reverie to concrete reality.

‘Do you laugh at me?’ the Hausa man asked.

‘No way’ he was happy for a beautiful house like this.

“Ye wa, na my uga bishop bud am” The Hausa man said.

“That’s good, we are here for Bishop Asomugha.”

“My uga?” The Hausa man asked.

“Ye wa” Chinagorom mimicked.

“Stop for here make I gwo tell am kwo.”

A leg of his, the left one was longer than the other and as he walked away he limped like a dwarf whose legs are not equal. And his gait was comical that they laughed with their tongues. Yes! With their tongues. They feared if he turned and got them laughing at him he might change his mind and use a miserable accent to tell them the bishop has travelled to America, just to keep them off. Very soon he staggered back, like he was oiled and zonked, and forcefully they contained the laughter that desperately pushed at their locked lips.

“Uga say make una come in.”

Laughter curled up from Chinagorom’s stomach to his throat but he spat it out like phlegm. Instead of a boisterous laughter that belched him it was a lumpy, frosty white substance that landed on the lawn beside the driveway.

A very huge tall man with the air of dignity, gold-rimmed spectacles with a darker-toned heavy missa, a southone of indigo-red with a brown ribbon dividing his waist so he was a perfect shape of number 8, ushered us into a blue-pink parlor of sofas upholstered with lavender soft linens.

“Soromtochukwu how are you, how are your parents?”

“Bishop they are fine, they now live in New Heaven.”

“God bless them, what should Odera offer you?” Odera was his house help, a boy of about twelve. He sat in the dining room. Waving at them.

“And who is this? Your brother?”

“No, he is not my brother. He’s my Sp in the school am retaking my SSCE.”

A look of worry took his face suddenly and Chinagorom prayed his expectation would not be cut off.

“An Ebonyian.”

“Yes sir.”

Chinagorom shivered. Hot dust with sharp grits collected in his mouth. He sniffed the rotten odour of cabbages and rag mats even when the guest room they sat in smelt of burnt incense. The Bishop might be an Enugu man, maybe one of those who believed the Ebonyians are dogs and barbaric and should not be talked to. But what’s wrong if he came from Ebonyi.

“Am planning to get a stranded Nun in Ninth mile. Tell me why you are here, her car broke down there and I need to get her. So how may I help you?”

“My Lord Bishop. He wrote a brilliant novel and he looked out for someone to publish it for him” after a moment of cursory gaze at Chinagorom. From his eyes to his toes, maybe he saw his tattered slippers he couldn’t tell, and said “What church did you attend?”

“Deeper Life Bible Church.”

“What?” he nearly hopped up.

“My lord bishop what’s wrong?” Soromtochukwu asked.

“Nothing dear….erm…erm, you see you are too young to scramble about for someone to publish you, your mates are busy studying in school. You must be a graduate before you write.”

“Sorry to interrupt you sir. Age is simply a number and if a story has a lesson to spread, I think it’s worth publishing if properly written regardless of the age of the writer.”

“Why are you not a catholic?…”

“What?” Chinagorom flung his mouth open. Soromtochukwu was disappointed in this Bishop. Before it was the Ebonyi thing now it was a church thing.

“Sir, why the question?”

“The money I have is from the catholic people, and am supposed to use it on the catholic people”

“My Lord Bishop meaning?” Soromtochukwu asked

“I cannot help him.”

Chinagorom wept and wept “Is it because I am not a catholic?”

“No, you will not go out there to tarnish my image. Not because you aren’t a catholic member but because I served the catholic people. Please Soromtochukwu take this one thousand naira and go back home. Am cashless here.” And the bishop drove out into the heart of Abakaliki. He wept, then cried and Soromtochukwu wept.

Back home, out of anger, his father collected his novel manuscript, burnt it to ashes, and threw him out of the house for wasting the money he’d have used to feed his family on a fruitless journey.

VII

Chinagorom heard the slow grunts and groans of Chinelo and her profusely weeping mother in her room as his father crossly screamed outside, flailing his hands erratically into the evening placidly wafting breeze that tasted the coriander herbs framing their small hut, telling him to walk out of his compound. The Effium evening sun busily crept back into the dimming skies and darkness progressively caved in. And he wondered where his father expected him to sleep tonight. His father was stern and uncontrollably staid. He knew his father when he’s angry over a point. He might kill. He’s a nice man built into a cold-blooded gladiator by the spasms and paroxysms of poverty and Chinelo’s cerebral palsy and the burden of his school fees. A God-fearing man tailored into skeptical shards of grenades. Heartless.

He had been kneeling before his father for hours, importunately begging for forgiveness, for wasting his money unnecessarily on a fruitless trip, but when he realized he had a hardened soul for a father he slowly stood up and indulgently stepped into the darkness. His father shook like the thyme leaves in a tsunami and waggled his head like an okito lizard yelling ‘leave my compound, come back here if you have my money’. Chinagorom was an inch out of the top of the entwined igrish woods bridging the gutter just a few steps away from the verandah when her mother’s scream came loudly from the left of his father. He halted and turned nervously. ‘Please dim oma. It’s two thousand naira only. He’d work for it, let him come in. He should be hungry since morning. Please, Chinelo said she’d die if his brother…’ and his father said ‘that one should not even talk. He is a jinx in my house. She should die. Am, to be frank with you, zonked and tired of that ogbanje. My house severed to this state as soon as she was born in Effium-Sudan Hospital. She came through cesarean operation and swept my pockets away from me with that cerebral palsy. She should die. ‘And you’ pointing at Chinagorom feverishly and bolting down from the mud pavement ‘leave my house. Go get me my money’. His father never believed he went to Abakaliki, he agreed he spent the money. Or saved it somewhere. Chinagorom wept and ran hastily and hungrily into the darkness.

He had no place to go and the night fell heavily. Effium was a small city you do not walk in at night because crime had gone haywire. It was in the night Obasimbom’s house was robbed and his daughter was raped to death. It was in the night a man’s shop was burgled in Uturu and because the man slept there his head was split open. It was in the night Crossper’s phone booth was broken. It was in the night a boy was killed in Ibenda. The night was a terror and a tremor in Effium and his father threw him out.

He was afraid as he climbed Okpakwa bridge into the Nwafia market. He was very hungry plus he had no place to go. The only place he could go to sleep tonight was Sorom’s house. How’d Sorom feel? And if she felt nothing what would her neighbors say? He concluded it was better to receive insults than to die. He must go. Sorom’s house was at asu-oji. He must follow to Nwafia market, the market people averted in the night. The place where the police loathed in the night. In the night, it was the rendezvous of the fornicators, the bunk of igbo smokers, the tryst of the derelicts and the scallywags; the port of call for criminals before a terrible thing would happen in the city. He would not follow ikpoki junction another road to the place. It was already filled with bad boys. Night hawkers and the cult boys sipping gin and booze, ogogoro and puffing marijuana and having fixes of heroin and methadone.

He was in the fringe of the market and his heart already pulsated. He walked slowly then paddled faster from Ozo Egburu to Ozo Jaki then to Ozo Okirika before he heard harsh whispers coming from his left, inside a store at Ozo Eba. And he made the worst mistake. He tiptoed gently towards the store. He stood beside the open door and saw seven boys around his age. They corked short guns and busily wore black hoods, a grown-up was among them and listening attentively he told the small boys to kill anybody that tried to stop them from breaking into Mr. Madina’s house. Mr. Madina was one of the richest men in Effium with policemen as gurads. He told them to go with plan x, follow road B, strike down the first two policemen at the gate and climb in through the back fence. No fuck up. The jav is twenty k. The boys laughed and began to sing a song. In the song they called themselves night wolves. Ready to kill. Ready to shoot and Ready to starve.

Chinagorom felt glued to the ground. He couldn’t believe the criminals that perturbed Effium were the night wolves, young boys of his age. They said a short prayer they called the prayer of benediction for the souls that would fall with the bullets tonight. As they made to flood out of the room, and as Chinagorom made to gently duck into a dark corner beside the store, someone tapped the nape of his neck. He bolted up and began to run faster. The someone was another grown-up. And one of them that could be out to smoke wee-wee. The man, all of the short boys scuttled after him. He ran faster and they ran faster too. As he got closer to ozo iyeri the first grown up screamed shoot him, shoot him, get him, get him down. And the boys screamed and triggered their guns incessantly. A bullet flew across his ear and he became sure he’d die if he continued to run, which he couldn’t with an empty stomach. He stopped, yelled ‘please don’t kill me’ and slumped on the ground face down.

Malaika was the first boy to reach him. He called on others. He told them ‘the guy is a small boy’. The first grown-up, Cabba, picked his weak shoulder up and asked what brought him to the bunk of the night wolves. He told them everything. How he dreamt of being a writer. How he travelled to Abakaliki and how his father threw him out. Cabba ordered Malaika to shoot him. To waste him. Malaika corked his gun, held the trigger then stopped. Chinagorom was weak on the ground and said ‘boss I feel for this guy’. Cabba yelled ‘I said kill him. He’s a ju man and he already heard our words, already seen our faces. He must die or we are all gone’. Yes! The boys chirped. Cabba said ‘Malaika if you can do it Dragon waste that shit. Dragon lifted his gun, corked his gun as he made for the trigger Malaika lifted his to his forehead. ‘You do it I finish you’ Malaika said. Cabba loved Malaika, losing him would be tantamount to losing a gem in the gang or else his action warranted death. ‘Ok’ Cabba said ‘what do you think?’ ‘I would give him an option’. If he fucked up. He’s going down now’. And he bent closer to Chinagorom. ‘Man, the truth be say you don fuck up. Any body way see the secret of the night wolves no de leave to tell am, but unto say I de consider, you choose between death and life by choosing from these options. One, you agree make you go into a blood convenant with us and become our member tonight? Or you agree make you die? Chinagorom whispered weakly ‘I am hungry’. Malaika gave him bread and butter. He got strength and Malaika continued. You one die or leave. Guy answer me we get work tonight.

Chinagorom looked up and down. Seeing they were ready to kill him to protect their lives. He nodded his head and they dragged him into the store for initiation into the coven of the Night Wolves.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!