By

Rupen Savoulian

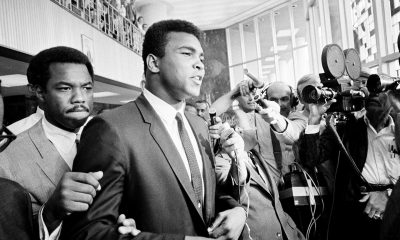

Tributes to the late great boxer Muhammad Ali have been overflowing since the announcement of his passing earlier this month.

John Wight has published an excellent two-part obituary to Ali in the pages of the Morning Star. He explores the life and times of Ali, elaborating on how Ali defied the odds in the boxing ring, but also defied the mainstream political tide outside of it. Standing up for his principles, Ali sacrificed his heavyweight champion, lost three prime years of his career, and earned the enmity of the predominately white media and sporting power structures. Wight ends his extensive and moving obituary with the observation, “He truly was the lion that roared.”

The details of the formative and key events in Muhammad Ali’s life are well known – his upset victory over the fearsome heavyweight boxer Sonny Liston in 1964, his early conversion to the Nation of Islam and name change, his staunch opposition to the Vietnam war and refusal to be conscripted which cost him three prime years of his career and financial loss, his stirring comeback and famous victory over George Foreman in 1974. Let us focus today on the things that Ali stood for, and how he demonstrated that athletes and activism combine in powerful ways. As Richard Eskow put it in an article for Common Dreams magazine, Muhammad Ali’s life and principled stand spoke to the activist soul.

Eskow elaborates in his article that:

In the end, Muhammad Ali wasn’t just the most important athlete of his time. And he wasn’t just a world-changing activist. He was even more than those things: he was a unified human being. His occupation was inseparable from his aspirations, his spiritual ideals inseparable from his worldly activities.

Ali’s conversion to the Nation of Islam represented both a spiritual, and a political, awakening. In a time of strict racial segregation, where being black meant that you were a second-class citizen, Ali found a home within the Nation of Islam. The latter, an exclusively African American organisation, demanded self-respect and proudly displayed its pro-Africa spirit in all of its activities. Yes, that organisation taught its members that the white man was the blue-eyed devil. A hostile attitude, but understandable, given the horrendous violence visited by the white power structures upon the African American communities. From the day that Jack Johnson, the African American, became the first black man to win the heavyweight boxing championship, the media and sporting bodies put out the call for a white man to win back the prestigious championship for the white race. When Johnson succeeded in maintaining his grip on the sport, there were race riots across the country – reprisals by enraged whites against black communities.

Dave Zirin, the sports journalist and political writer explained in one of his articles;

The backlash against Johnson meant that it would be twenty years before the rise of another black heavyweight champ — Joe Louis, “the Brown Bomber.” Louis was quiet where Johnson was defiant. He was handled very carefully by a management team that had a set of rules Louis had to follow including, “never be photographed with a white woman, never go to a club by yourself and never speak unless spoken to.”

Johnson himself was hounded and jailed on the most dubious pretexts in order to maintain the colour line in sport.

Ostracised and vilified by white America, it is no wonder that Ali found a spiritual home in the separatist Nation of Islam organisation. As Ali himself explained it in April 1968, during his three year banishment from boxing; “We don’t hate white people – we know them too well”. When he was banned from boxing, Ali lost his main income stream, going from a wealthy status to borderline pauper. Okay, not exactly poverty-stricken, but in dire financial straits. The threat of incarceration hung over his head.

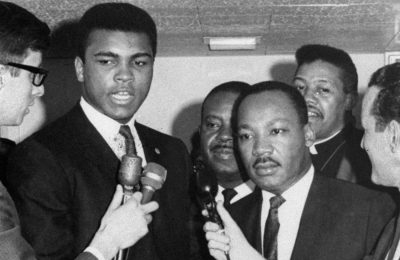

Ali demonstrated that the bridge from the anti-war movement of the 1960s, when he refused induction, and the civil rights movement, which demanded racial and economic equality, was not that large an obstacle to cross. During Ali’s time in boxing exile, he continued speaking out against the war in Vietnam, and he maintained his absolute commitment to civil rights. This in a time when civil rights leaders, such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, were killed because of their principled commitment.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Muhammad Ali speak with reporters in Louisville (AP Photo)

Ali-Frazier rivalry

One of the few boxers who helped Ali during his years of exile was Joe Frazier. The latter, the son of South Carolina sharecroppers, used and developed his athletic talents for boxing and emerged from obscurity, much like Ali. Frazier and Ali shared an intense boxing rivalry, one that spilled out of the ring. After Ali’s boxing license was reinstated in the early 1970s, Ali and Frazier fought three gruelling matches. In their first encounter, in 1971, Frazier handed Ali a rare defeat, hitting Ali straight in the head with his fearsome left hook, sending Ali tumbling down to the canvass. Frazier won that fight through sheer determination and persistence.

Ali had characterised Frazier in the pre-match buildup as an ‘Uncle Tom’ character, a pawn of the white establishment. This was particularly unfair – Frazier’s background in poverty was typical of black America. Cruelly labeled a ‘sellout’, Frazier could never quite shake off that tag. This was unfortunate, and Frazier was nothing but an honest, talented fighter. He was definitely not an intellectual – but then neither was Ali. After fifteen bruising rounds, Frazier defeated Ali, and for that, the white sporting establishment were gleeful – the draft-dodging traitor, the uppity black Muslim was hit on his head, and knocked down on his butt.

After his victory, Frazier was invited to address both houses of the South Carolina legislature. Not because the white politicians were particularly interested in Frazier, but because he was the black man who had finally knocked down Muhammad Ali. The latter had berated Frazier at every opportunity as a sellout, the white man’s champion – an unfair characterisation. However, Frazier did stand in the South Carolina legislature, at the time still draped in Confederate flag of the former slave-owning state. Frazier was not an ‘Uncle Tom’, but he was naive in his belief that the white establishment respected him as a fighter. As the 1970s moved on, the taunts and insults to Frazier from Ali became less political and more personal. The verbal humiliations only added to Frazier’s anger, and in their fights, Frazier turned all that anger into furious energy, pummeling and battering Ali. We will come back to point later.

Frazier only generated interest insofar as he defeated Ali. Frazier, a heavyweight champion in his own right, was subsequently defeated by George Foreman. The South Carolina politicians quickly lost interest; the swooning media stopped following Frazier, and he was relegated to the status of just another fading ex-champion. As Dave Zirin explained in his article about Joe Frazier, written soon after the latter died of liver cancer in 2011:

This shouldn’t have been Joe Frazier’s fate: the convenient hero of everyone who wanted to see Ali punished for his politics. This shouldn’t have been Joe Frazier’s fate: internalizing and nursing every barb from “Gaseous Cassius” instead of letting it roll off his back. This shouldn’t have been Joe Frazier’s fate: rejected by the same establishment so quick to embrace him when it suited their needs. Smokin’ Joe deserved so much better.

The Seventies

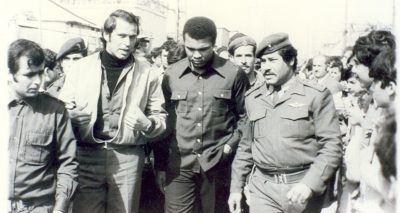

In the 1970s, as the mood of the country changed and the Vietnam war was concluded, Ali was welcomed back into the fold. He continued to box, but also took the time to extend his political commitment – he visited a Palestinian refugee camp in South Lebanon, expressing his support for the cause of Palestinian self-determination. He visited and toured the former Soviet Union in 1978, where he was just as popular as in Africa, America and other parts of the world.

Muhammed Ali in a Palestinian refugee camp in southern Lebanon, 1974

Ali had already visited a number of countries in Africa back in the 1960s, touring Ghana and meeting with then-president, the Pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah. Ali was welcomed as a hero, and he also visited Nigeria and Egypt. A continent that had been ignored by so many Americans, dismissed as an exotic jungle land full of savages, Ali took the time to understand its history and humanity, and the ravages visited upon it by foreign imperialism. Ali demonstrated a sharp political acuity, something quite rare in professional athletes. He gave courage to those who were struggling to find theirs.

After the famous fight with George Foreman – the rumble in the jungle, where Ali regained the heavyweight championship by defeating Foreman – his skills and health went into decline. For that fight, Ali used his now famous tactic, the rope-a-dope, where he waited, absorbing the powerful blows by Foreman, letting the latter exhaust himself. Ali waited, allowing the strong Foreman to pound away, round after round. By the middle of round five, Foreman was tired out. Note that prior to Ali’s banishment from boxing, he demonstrated his remarkable reflexes and footwork to avoid getting hit, while hitting his opponents. Now, he is getting hit – hit hard, and frequently. Foreman, Joe Frazier – these were only two of the hardest hitters in boxing at the time. Ali’s body is taking a barrage of punches – his kidneys, stomach, liver, rib cage, head – are all being battered repeatedly. He hurt himself in the fights of the 1970s. The physical decline had set in.

After Foreman, Ali had a number of fights; some were very strong encounters, some were ridiculously farcical bouts. The 1980 fight with Larry Holmes should never have happened; Holmes was an upcoming heavyweight contender, who had sparred with Ali in the 70s. Ali was in no condition to fight, and Holmes proceeded to batter a helpless Ali for ten rounds. As Thomas Hauser, a boxing writer and Ali biographer explained it:

Holmes, who was eight years younger than his opponent, dominated every minute of every round. It wasn’t an athletic contest; just a brutal beating that went on and on.

That was the night that Ali screamed in pain. After ten rounds, Ali’s corner threw in the towel. Although he won, Holmes was upset and depressed after that fight, and was reduced to tears because he had demolished his idol and hero.

The physical deterioration had set in, and Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 1984. In his retirement years, Ali was feted as a sporting icon – there is no doubt that he was. However, his political courage was largely forgotten, as he was reduced to a sanitised sporting hero. Ali maintained his humanity in an otherwise barbaric sport. He exhibited not only physical courage, but grace and elegance, and was articulate at a time when boxers and super-star athletes were not known for any particular skills outside of their chosen profession.

There is so much more to Ali’s life that we could go into; however, other writers have covered that ground. Let us remember Ali as the powerfully articulate, gregarious and superb athlete-activist that he was. He was prepared to sacrifice his individual sporting success for his beliefs. He was not only shaped by the political and social context of his times, but actively shaped and contributed to it. It is a testament to his political vision that, even towards the end of his life, as he remained hobbled by Parkinson’s illness, he still showed political awareness and perspicacity.

In December 2015, presumptive Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, who is not noted for his intellectual capacities, made a startling call for a complete ban on Muslim immigration to the United States. Muhammad Ali, who had left the Nation of Islam and joined the mainstream Sunni Islam in the mid-1970s, was asked for his comments. In fact, Ali had been gravitating towards the Sufi denomination of Islam since 2005, revealing his commitment to a spiritual quest. While not directly addressing Trump’s remarks, Ali, through his spokespeople, had the following to say:

We as Muslims have to stand up to those who use Islam to advance their own personal agenda . . . I am a Muslim and there is nothing Islamic about killing innocent people in Paris, San Bernardino, or anywhere else in the world . . . True Muslims know that the ruthless violence of so called Islamic Jihadists goes against the very tenets of our religion.” “I believe that our political leaders should use their position to bring understanding about the religion of Islam and clarify that these misguided murderers have perverted people’s views on what Islam really is.

Rather than lashing out at the obnoxious, bombastic bigot, Ali chose to ignore the ignoramus, calmly and rationally addressed the issues at hand, explained his position, and rebuffed the ignorance and hatred at the core of Trump’s remarks. Ali demonstrated an understanding of the political and social hot-potato issues of our times – an understanding far superior to that of the cartoonish, racist buffoon masquerading as a politician.

Let us salute the lion that roared – his resistance to imperialist war overseas and racist power structures at home is a lesson from which we can all learn.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!