By

Rupen Savoulian

Naim Suleymanoglu, born in Bulgaria of Turkish descent, is a world champion weightlifter. Born Naim Suleimanov in 1967, his talent for weightlifting was recognised at an early age. Sent to a special school for budding weightlifters, his coach called him a child prodigy, and the wonder kid was set for a remarkable career. He did not disappoint, going on to become one of the most distinguished weightlifters in Olympic history.

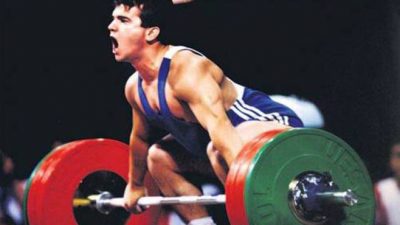

Of small stature, standing 1.47 metres (4-feet 11-inches), and weighing 60 kilos, he has lifted three times his own bodyweight above his head, broken numerous world and Olympic records, and won three gold medals for the featherweight class in weightlifting. Earning the nickname the ‘Pocket Hercules’, watch an example of Suleymanoglu in action at the 1996 Olympic games. He lifted three times his own body weight, making him pound-for-pound one of the strongest weightlifters to ever compete.

He competed in the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, but failed to win a medal. He retired soon after.

There is no doubt that Suleymanoglu deserves his fame and success. He is a remarkably talented individual athlete and a fierce competitor. He earned renown for himself, and distinction for Turkey, the country he represented. In 1996, he dueled with the Greek weightlifter Valerios Leonidas, each competitor outdoing the other in terms of lifting, until only one (Suleymanoglu) emerged victorious. He owes his fame to his outstanding ability as a weightlifter. However, that is not the only reason he became a world-famous sporting figure.

Suleymanoglu was born in Bulgaria, in the days of the Communist system. He competed initially for Bulgaria in various world championships, and Bulgaria was known, along with the Russians and East Germans, to produce top-class weightlifters. In the mid-1980s, when Suleimanov (his birth name) was 16, the Bulgarian government joined the Soviet boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. Suleimanov missed a chance to win gold.

From 1984 onwards, the Bulgarian government decided that the Turkic minority within its borders, numbering around 900,000, would have to assimilate. The Bulgarian Turks, allowed to practice their religion and maintain their traditional culture in the early days of Communist rule in the 1940s and 1950s, were now forced to Bulgarianise their names, abandon their religion of Islam, and those who refused were allowed to migrate to Turkey. The Bulgarian government in the mid-1980s, under the strongman Todor Zhivkov, was attempting a last-ditch measure at populistic nationalism to shore up support for a stagnating regime. The Turkish minority resisted, attacking the authorities, and in May 1989, mass demonstrations erupted.

The Zhivkov leadership decided that those Bulgarian Turks who did not wish to remain in Bulgaria would be allowed to proceed to Turkey. The latter has always portrayed itself as the logical homeland, the big brother of the pan-Turkic family. The opportunity to move out of the Eastern bloc and proceed to the ‘free’ western country of Turkey was too big to miss. Thousands of Bulgarian Turks packed up and fled to what they believed was the relative safety and freedom of Turkey.

Suleimanov had already left his native Bulgaria – he defected to Turkey in 1986 while he was a competitor for the Bulgarian weightlifting team in Melbourne, Australia. Turkey had long desired that Suleimanov, now going by his Turkish name of Suleymanoglu, compete for their weightlifting team, thus earning them long-sought glory as opposed to the usually dominant Bulgarians. The motives of the Turkish side were not completely altruistic – and later it emerged that Turkey paid the Bulgarian government seven million dollars (US) for Suleymanoglu. Big money for a star athlete. The Bulgarian Turks were outcasts, unwanted in their native land. They sought refugee in their ethnic home country. But how were the thousands of other Bulgarian Turk refugees treated by the Turkish authorities?

with Turkish Prime Minister Turgut Özal 1986

There is a small pamphlet, printed by the Bulgarian government in 1989 during the last months of Communist Party rule. It is called “The twilight of a delusion: stories of Bulgarian citizens who returned from Turkey”. Authored by Georgi Naidenov, it documents the callous mistreatment, abuses and neglect suffered by the Bulgarian Turks who chose to move to Turkey. It is a collection of testimonies from the refugees themselves, seeking what they thought would be a new life in the West, only to be shunted aside, maltreated and demonised by the Turkish authorities. 300,000 people made the ‘Big Excursion’ from Bulgaria to Turkey – about half then returned. Pushed into makeshift refugee camps, beaten, abused and malnourished, the stories of the refugees makes for heart-rending reading. The delusion of finding freedom and prosperity in a capitalist country had been rudely shattered. They picked up and returned to their native Bulgaria.

Indeed, by August 1989, a few months after the initial wave of refugees arrived at Turkey’s borders, the Turkish authorities announced that they would be re-closing their borders. The Ankara government expressed its policy reversal after concerns about the ability of the Turkish economy to absorb the recent migrants. The promised utopia was now closing its gates.

By the end of 1989 the Zhivkov government had changed – the Communist party was ousted, and a new pro-capitalist formation took its place. The borders between Bulgaria and Turkey were opened, and the Eastern bloc was now open to a mass influx of big capital and business from the imperialist West. Suleymanoglu had long since left Bulgaria, and had long since forgotten his Bulgarian Turkic origins, going on to break world and Olympic records in weightlifting.

In 2009, the Sofia Echo, the Bulgarian news agency, published a retrospective account of the exodus of the Bulgarian Turks on the twentieth anniversary of that event. The article provides an overview of the period, the measures by the Bulgarian government of the time, and the experiences of the refugees. One refugee in particular, Serkan, is quoted at length. He was fourteen at the time, but for him, the wounds of the past have not healed. His comments shed light on the particular experiences of the Bulgarian Turks who were reviled, ignored and marginalised by their supposed brethren in Turkey. Detailing his journey, the article quotes Serkan’s revealing account:

“The capitalist economy (in Turkey) was a big shock to us,” says Serkan. “We went through a difficult period adjusting to a system which was alien to us. In addition, we had to co-adjust to a religion that until then hadn’t played a big role in our lives.”

Serkan tells how when his family returned to Bulgaria in 1991 (by that time in the post-Communist area) they waged a legal battle to recover their Turkish names. They also had to buy back their original home at three times the price they had sold it for.

Note that readjusting to a capitalist economy was an enormous cultural and economic shock for the refugees. They had been forgotten, abandoned to their fate once the dust had settled, and no-one was concerned about their status as a marginalised minority anymore. They had been used as pawns in political propaganda. The wonder kid Suleymanoglu was now firmly ensconced in the Turkish weightlifting community; the rest of the Bulgarian Turks had to face circumstances as best they could.

It is not strictly accurate to suggest that Suleymanoglu completely forgot his origins, because he did actually remember his home community. In 2007, Suleymanoglu stood as a political candidate in Turkey for the ultra-nationalist and racist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). Informally known as the Grey Wolves, this party advocates an ethnically pure Turkish state, calls for the expulsion of ethnic minorities, and agitates for the re-emergence of a pan-Turkic empire encompassing the Turkish-speaking republics in Central Asia. The Bulgarian Turks are viewed, not as a ethnic minority struggling for equal rights, but as a foothold in an ever-increasing Turkish empire that seeks territorial and economic expansion. The Grey Wolves are one current in an ongoing rise of neo-fascistic and ultra-rightist parties throughout Europe.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the African American basketball athlete, competed fiercely in his chosen sport, built his career, and succeeded in establishing himself as a remarkably talented professional. Long since retired, he has never forgotten his African American origins, giving back to the community that nurtured him. A regular author and cultural critic, Abdul-Jabbar has spoken out on issues of racism and injustice in the United States. He penned a thoughtful, intelligent essay about the impact of an unequal class system on the black community in the US today. In fact, he wrote an article recently for Jacobin magazine explaining how college athletes, which he was, are still a vulnerable segment of society, subjected to an unscrupulous system that exploits their talents. He reached the heights of sporting greatness, but has never forgotten the humble origins.

As for the Bulgarian Turks, they are still an outcast minority in an economy that has considerably worsened since the reintroduction of capitalism. The Zhivkov-era certainly had its problems, of that there is no doubt. However, a state-subsidised health care system meant that the elderly and disabled were taken care of; children had enough to eat and were properly schooled; today, only a minority are better off, as the majority are stuck in poverty. Even the New York Slimes had to admit that while on the surface everything looked fine – free speech, free press and so on – beneath the surface was economic suffering, with Bulgaria still one of the poorest countries in Europe. As the British Express newspaper stated (hardly know for its socialistic sympathies), Bulgaria remains a melting pot of poverty and corruption.

We must never begrudge anyone their success, and Suleymanoglu is thoroughly deserving of all the accolades he has earned over his illustrious career. But we must also never forget our origins, and dispense with the delusion that capitalism provides a level-playing field. The commercialisation of sport is a poison, where individual talent is financially rewarded but subjected to the ultra-competitive imperatives of profit-driven corporatisation. An athlete becomes a brand name, valuable only insofar as they generate profits for their sponsors. Suleymanoglu did not understand, or perhaps could not understand, the economic forces that drive inequality in life are also dominant in driving commercial inequality in sport.

This article was originally published in February 2015 and is reprinted today with the kind permission of its author Rupen Savoulian

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!