AP photo

By

Binoy Kampmark

“Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.”

Susan Sontag, On Photography (1977)

The photograph is a still image of messages, trapped fleetingly. For that reason, it has been seen as mimicking death, a mask forever preserved. It suspends, a captured meaning hovering in time. That such images become weapons is undeniable. Not all are poetic notices to the great and the good. They are often reminders of the bountifully nasty, an inspiration for what is to come.

The photograph taught us, effectively, a new visual code, a Susan Sontag reminds us. In instructing us on that code, “photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe.”

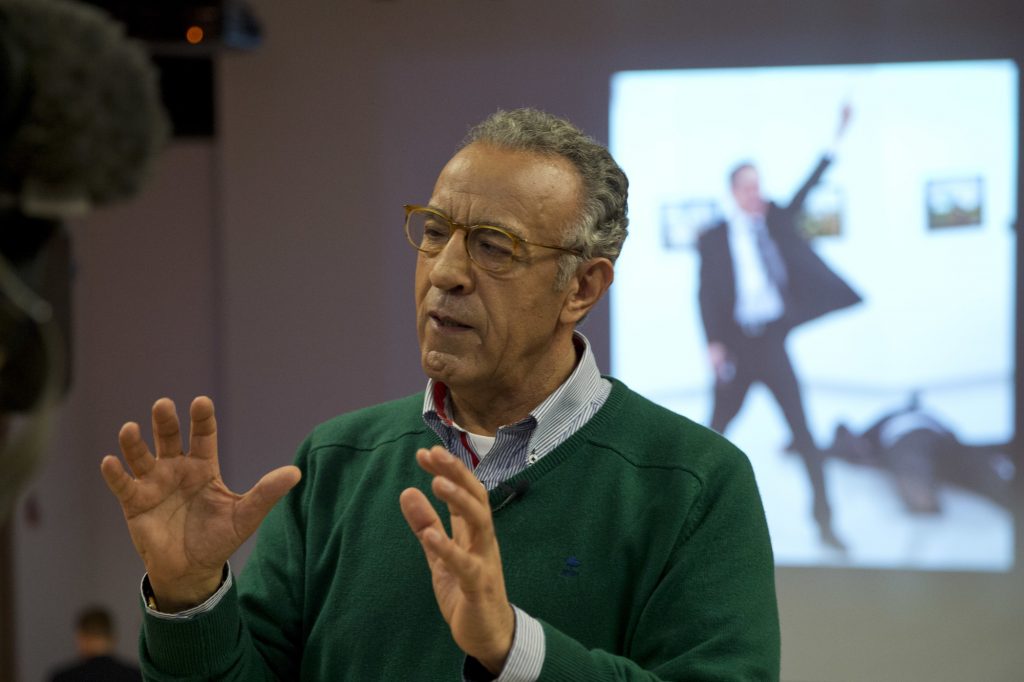

The right as what to observe, and what is worth looking at. The award of the “World Press Photo of the Year” Burhan Özbilici’s dramatic shot featuring the slaying of Russian ambassador Andrei Karlov in an Ankara art gallery is one such example, a fistful of tensions and discomforting points. It has divided and abhorred judges; it has drawn out parallels and debates.

The image, featuring a snappily dressed, committed man, is now generally known: The triumphant Mevlut Mert Altintas raises an arm, eyes ablaze, gun discharged, verging on hyped caricature. He extols the virtue of his act; for him, undeniably clear in its vicious beauty, its ideological clarity. The shots have been made, and his bloody work lies on the museum floor. The ambassador, Andrei Karlov, is dead.

The photo captures an insistence, the unqualified nature of this action (true fundamentalists are characterised by their lack of contradiction, their inability to see it). The ambassador needed to die to make a statement, and his rumpled figure, dead or dying, has become part of the gallery.

It has also become part of the register of geopolitics: Turkey’s confused relationship with Russia, sometimes intensely hot, occasional lovers with purpose; other times glacially vindictive, demanding loud resolution. In the background of the killer’s cries: the sea-deep blood bath of Syria, the haunting corpses of Aleppo.

Some have claimed that endorsing the photo as a winner of a contest would give it an unintended, propagandistic boost. Stuart Franklin, the chair of the committee whose decision he ultimately went against, admits to being tormented by his decision not to endorse the photo as the image of the year.

He admires the photographer’s sense of chance, his “composure, bravery and skill”. “It’s the third time that coverage of an assassination has won this prize, the most famous being the killing of a Vietcong suspect, photographed by Eddie Adams in 1968.”

Then, he elaborates on his reasons, the lukewarm, unconvincing grounds of a chairman confused and in need of self-respect. “I voted against. Sorry, Burhan. It’s a photograph of a murder, the killer and the slain, both seen in the same picture, and morally as problematic to publish as a terrorist beheading.”

Franklin, numbed by the current infatuation with staged dramas of beheadings, killings and terrorist indulgences, can only fear what a prize would do for such an image. “Placing the photograph on this high pedestal is an invitation to those contemplating such staged spectaculars: it reaffirms the compact between martyrdom and publicity.”

This is essentially a silly, if not meaningless argument and Franklin reveals the very reasons why such an image deserves circulation, discussion, and tears. A person about to lose his life to the swift application of sword, the bone and vessels severed, the life transported, shifted, removed, would be powerful, terrifying and no less poignant.

That it has a political message is beside the point: all such pictures do. There will always be a higher form of meaning to ground the reaction: the photo merely teases the surface, opens windows without ever showing us the whole room of feeling.

Franklin’s reasoning collapses as he garnishes his argument with nonsensical piffle. “Unlike the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914, the crime had limited political consequences.” The statement is that remarkable as to beggar belief.

The “crime” (others prefer the traditional reference of assassination) propelled Europe into a war that destroyed a continent, eliminated the monarchical structure, a generation and much else besides. Ridiculous as it is to blame the confused yet determined Gavrilo Princip for all that, the enormity of the act to historical destiny remains unquestioned. Pictures remain, for all the fuss, records, ideas that capture a moment in time for posterity. There are no foolish pictures, only foolish people.

Broader objections to pictures as propaganda tend to confuse the criteria of best photo with the endorsement of political content. These matters are not necessarily linked, and should not be confused. To appreciate the terrifying moment of a historical fact is not the same thing as agreeing with it. They can only be appreciation, pity, and awareness. The stunning cloud that arises from the atomic bomb that levelled Hiroshima enchants even if it is murderous and piteous.

A reminder to Franklin: The Vietnam conflict is forever caught by that moment where a young girl, naked, retreats in the face of napalm, her skin itself peeling, torn, sizzling before the effects of a US airstrike. The pro-war advocates opposing the communist juggernaut, blind to nationalist specifics, detested the image as being unduly propagandistic. Each action, each image, that militated against a cause was also one that was seen to embrace it.

Photography remains the terrain where we fight our pre-existing impressions, and perhaps hope for something better. A murder, viciously executed in the presence of art (life being short, art being long), is as suitably outrageous as any. This is not propaganda, but life and death, in all its captivating cruelty, snapped for posterity.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!