AI photo

By

Amnesty International

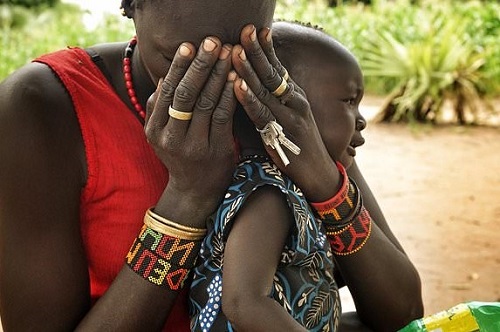

A recent military offensive in South Sudan’s Unity State was fuelled by the South Sudanese authorities’ failure to prosecute suspected war criminals, giving them ‘free rein’ to commit further atrocities in the region, human rights NGO Amnesty International said in a new report published.

The report, ‘Anything that was breathing was killed’: War crimes in Leer and Mayendit, South Sudan’ is based on the testimonies of some 100 civilians who fled an offensive by government forces and allied youth militias in southern Unity State between 21 April and early July this year – a week after the latest ceasefire was brokered on 27 June.

The brutal offensive included the murder of civilians, the systematic rape of women and girls and large-scale looting and destruction. Civilians were deliberately shot dead, burnt alive, hanged in trees and run over with armoured vehicles in opposition-held areas in Mayendit and Leer counties.

Following a military offensive that took place in Unity State in 2016, Amnesty identified four individuals suspected of responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity and called for an investigation. The South Sudanese authorities did not respond to these warnings, and recent UN reports have suggested that some of the individuals Amnesty identified may also have been involved in the atrocities committed during the offensive this year.

Joan Nyanyuki, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for East Africa, said:

“A key factor in this brutal offensive was the failure to bring to justice those responsible for previous waves of violence targeting civilians in the region.

“Leer and Mayendit counties have been hard hit in the past, and yet the South Sudanese government continues to give suspected perpetrators free rein to commit fresh atrocities. The result has been catastrophic for civilians.”

Civilians murdered in villages and swamps

Unity State has witnessed some of the most ruthless violence since the conflict in South Sudan started nearly five years ago. Dozens of civilian women and men told Amnesty how during the recent offensive, soldiers and militias used amphibious vehicles to hunt down civilians who fled to nearby swamps. Survivors described how groups of five or more soldiers swept through the vegetation in search of people, often shooting indiscriminately into the reeds.

Nyalony, an elderly woman, told Amnesty she witnessed soldiers killing her husband and two other men:

“When the attack started, early in the morning while we were sleeping, my husband and I ran to the swamp together. Later in the morning, after the fighting was over, the soldiers came into the swamp looking for people, and sprayed the area where we were hiding with bullets. My husband was hit; he cried out in pain. He was still alive, though, and the soldiers caught him, and then they shot him again and killed him. He was unarmed and wasn’t a fighter; just a farmer.”

Those unable to flee – especially the elderly, children and people with disabilities – were often killed in their villages. Several people described how elderly relatives or neighbours were burnt alive in their tukuls – traditional dwellings – and one man over 90 years old had his throat slit with a knife.

Nyaweke, a 20-year-old woman, told Amnesty she witnessed soldiers shooting her father and then murdering several children in the village of Thonyoor in Leer county:

“There were seven men [soldiers] who collected the children and put them into a tukul and they set the tukul on fire. I could hear the screaming. They were four boys. One boy tried to come out and the soldiers closed the door on him. There were also five boys whom they hit against the tree, swinging them. They were two [or] three years old. They don’t want especially boys to live because they know they will grow up to become soldiers.”

Other survivors described similarly horrific incidents, including one in Rukway village in Leer, where an elderly man and woman and their two young grandsons were burnt to death in a house. When their daughter ran out, carrying a small baby, a soldier shot her and crushed the baby to death with his foot.

‘They lined up to rape us’

Survivors also told Amnesty that government and allied forces abducted numerous civilians, primarily women and girls, and held them for up to several weeks. Their captors subjected them to systematic sexual violence, with many women and girls gang-raped. Those who tried to resist were killed. One interviewee said a girl as young as eight was gang-raped and another woman witnessed the rape of a 15-year-old boy. In one village alone, Médecins Sans Frontières reported treating 21 survivors of sexual violence in a 48-hour period.

A 60-year-old man described finding his 13-year-old niece after she was gang-raped by five men:

“My brother’s daughter was raped and she was going to die. When they raped her, we came and found her and she was crying and bleeding … she couldn’t hide … she told me she was raped by five men. We could not carry her and she could not walk.”

In addition to being raped, many of the abducted women and girls were subjected to forced labour, including carrying looted goods for long distances, as well as cooking and cleaning for their captors. Some of those abducted – including women and men – were held in metal containers and were beaten or otherwise ill-treated.

Looting and destruction of vital food supplies

Government forces and allied militias engaged in massive looting and destruction during their attacks in Leer and Mayendit, apparently aimed at deterring the civilian population from returning. They systematically set fire to civilian homes, looted or burned food supplies, and stole livestock and valuables. Many survivors returned home from weeks or months in hiding only to find that everything had been destroyed. This deliberate attack on food sources came as civilians in Leer and Mayendit were just beginning to recover from a famine that had been declared in their counties in February 2017 – the first time since 2011 that famine was declared anywhere in the world.

Vicious cycle fuelled by impunity

Amnesty previously visited Unity State in early 2016 and documented violations that took place during the previous military offensive on southern areas of the state, including Leer county. Amnesty later identified four individuals suspected of responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity and called on South Sudan’s military chief-of-staff to investigate them. There was no response.

Joanne Mariner, Amnesty International’s Senior Crisis Response Adviser, said:

“It’s impossible to ignore the cruel reality – if the South Sudanese authorities had acted on our warnings back in 2016, this latest wave of violence against civilians in Leer and Mayendit might have been avoided.

“The only way to break this vicious cycle of violence is to end the impunity enjoyed by South Sudanese fighters on all sides. The government must ensure that civilians are protected and that those responsible for such heinous crimes are held to account.”

Amnesty is urging South Sudan’s government to end all the abuses and to immediately establish immediately the Hybrid Court for South Sudan, which has been in limbo since 2015. Additionally, the United Nations Security Council must enforce the long-overdue arms embargo adopted in July.

Amnesty International is a non-governmental organisation focused on human rights with over 7 million members and supporters around the world. The stated objective of the organisation is “to conduct research and generate action to prevent and end grave abuses of human rights, and to demand justice for those whose rights have been violated.”

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!