By

Anant Mishra

Introduction

Nigeria has a history of Islamist sects within its borders. Not all have been violent movements, some existing peacefully in parallel with the state. And not all of Nigeria’s violent sects are Islamist; one such is the Ombatse cult, which clashed with security forces in Nasarawa state in May 2013.

Until Boko Haram’s transition to extreme violence, perhaps the most virulent of the radical Islamic movements was the Maitatsine uprising in the 1980s or the Yan Shi’a movement in the 1990s. But all of these movements could be described as international in some respect: their members or ideologies all crossed beyond Nigeria’s northern borders, or they referred to global models of Islamism in Iran or Saudi Arabia.

Now defined as an international terrorist organisation, Boko Haram is no different in this regard. There is a lot of speculation about the sect and its links with foreign jihadists. But it is its splinter group, Ansaru, that exhibited much more potential to become Al-Qaeda’s Nigerian affiliate. Unlike al-Shabaab in Somalia, Boko Haram has no known connections to Nigeria’s diaspora. This northeastern violent extremist sect has fused itself to external ideological influences and the tools of global communication but, while benefiting from porous borders, it has remained focused on Nigerian targets and has echoes of other African uprisings that grew out of social grievances. It mutated into a fanatically violent terrorist movement with shades of cultist and criminal motivations over a period of years of mishandled responses by government and security forces.

A peculiarity of Boko Haram in Nigeria is not its criminality but the sectarian nature of its agenda, which is distinct from the dynamics of resource-driven localised violent conflicts between different ethnic groups in Plateau state, or the ethnic claims of insurgent groups such as the O’odua People’s Congress (OPC), the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) and the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB).

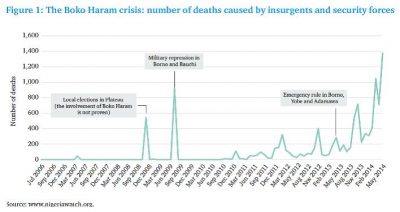

Based in Nigeria’s semi-arid northeast, Boko Haram does not have access to the economic leverage of oil to pressure the government. It adopted the iconography and some of the tactics of foreign jihadist movements, in particular suicide attacks, which had never before been seen in Nigeria. But while this and the extreme nature of its violence, including against children, is of such significant international concern that more countries are becoming engaged in the security response to the crisis, Boko Haram’s ideology and tactics do not prove sustained international operational connections and coordination. International interests were much more threatened by MEND in Nigeria’s oil-producing Niger Delta. Since attracting international headlines with the kidnapping of some 270 schoolgirls in April 2014, Boko Haram has commenced a territorial offensive in the northeast that Nigerian security forces have struggled to reverse. Boko Haram’s attacks are not limited to the northeast, and the group is increasingly active in neighboring countries. By some estimates, more than 5,500 people were killed by the group in 2014, making Boko Haram one of the world’s deadliest terrorist groups. Boko Haram raids and bombings in early 2015 have claimed hundreds of lives.

Nigeria begins 2015 facing highly polarising—and potentially destabilising—elections amid a dangerous territorial advance in the northeast by the violent Islamist insurgent group Boko Haram. By some estimates, more than 5,500 people were killed in Boko Haram attacks in 2014, Boko Haram attacks having already claimed hundreds of lives in early 2015. In total, the group may have killed more than 10,000 people since its emergence in the early 2000s. More than 1 million Nigerians have been displaced internally by the violence, and Nigerian refugee figures in neighboring countries continue to rise. State Department officials have suggested that the planned elections may be a factor in the increased tempo of Boko Haram attacks, as the group seeks to manipulate political sensitivities and undermine the credibility of the state as the polls approach.

The Source

The movement remains mysterious, with little evidence to substantiate different allegations about its true agenda. Since the kidnapping of the Chibok schoolgirls in Borno state in April 2014, which drew an unprecedented level of international media attention to the movement, Boko Haram has been portrayed as anti-women, anti-Christian, anti-education and terrorist.

According to the Office of the National Security Adviser (NSA) to President Goodluck Jonathan, ‘the sect is ideologically linked to Al Qaeda’ and ‘it rejects peaceful coexistence with Christians’. While these facets related to gender, religion and politics are all correct; they paint an incomplete picture and on their own limit the understanding of a group that has mostly killed Muslims and young men. This incomplete focus also detracts from a contextual understanding of how the movement developed and became increasingly criminalised over a period of years during which civilians have also been killed by security forces. The sect’s real name is the ‘Sunni Community for the propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad’ (Jama’atu Ahlis-Sunnah Lidda’awati Wal Jihad). Nicknamed Boko Haram (‘Western education is prohibited’), it was founded around 2002 by Mohammed Yusuf, a radical preacher based in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state. Its original source of inspiration came from the Movement for the Eradication of Heresies and the Implementation of Sunnah, known as the Izala (‘Eradication’), a Nigerian Wahhabi Salafi organisation created under the aegis of Sheikh Mahmud Abubakar Gumi in 1978. The difference, however, is that the Izala reject armed struggle. While they have personnel, the yan agaji (‘those who help’), to police their religious meetings, favour negotiation over confrontation with the state.

The Weaker State

There is an intricate link in Nigeria between politics, governance, corruption, poverty and violence. Politics is largely driven by money. Elected officials are hardly accountable to citizens. The well-connected exercise undue influence according to the strength of their purse and the strings they can pull. The various elite factions – political, economic/business, bureaucratic, traditional and religious – have been drawn into a political economy driven by huge oil receipts and implicated in wide scale and systemic corruption. Nigeria is consistently ranked as one of the most corrupt countries. This has denied millions opportunities. According to former World Bank Vice President for Africa Dr Obiageli Ezekwesili, it has lost more than $400 billion to large-scale corruption since independence in 1960. When corruption and clientelism do not work, politicians often revert to violence to achieve their aims. “Godfathers” use thugs and militias to intimidate opponents and in the vicious, sometimes deadly struggles for local power or against other ethnic or sectarian groups. The financial recklessness and extravagance of many former (and serving) governors is well documented. Debts have soared, and many states face bankruptcy.

Some of the money used for corruption, patronage and political violence by governors comes from “security votes”, joint state/local government accounts and money laundering. The “security vote” is “a budget line that is meant to act as a source of discretionary spending that the executive can use to respond quickly and effectively to threats to peace and security.”

Accessing the Threat

After the 2009 crackdown, Boko Haram went underground for a year before surfacing with attacks on police, their stations and military barracks to avenge the killings of Mohammed Yusuf and other comrades. The group also carried out jailbreaks to free members and demanded the prosecution of Yusuf’s killers, release of detained colleagues, restoration of its destroyed mosque and compensation for members killed by troops.

Originally directed mainly at security forces and government officials, the campaign has expanded to include attacks on Christians, critical Muslim clerics, traditional leaders, suspected collaborators, UN agencies, bars and schools. It has evolved into terrorism, including against students at state (secular) schools and health workers involved in polio vaccination campaigns.

From targeting security services, Boko Haram expanded its attacks to assassinating neighborhood chiefs who it believes helped troops identify members and Muslim clerics who opposed their ideology. They also started killing Borno state ANPP politicians, who they claim reneged on promises. “After the politicians had created the monster”, a former SSS officer said, “They lost control of it”. Victims included Modu Fannami Gubio, a gubernatorial candidate, Modu Sheriff‘s cousin, shot with five others outside his family house in Maiduguri on 28 January 2011; and Awana Ngala, ANPP’s national vice chairman, shot in his home with a friend on 27 March 2011 (just over a month before that year’s general elections). This led the ANPP to accuse the rival PDP of orchestrating the killings. The “ECOMOG” thugs also became targets; most were forced underground, while others fled Maiduguri. The local population is convinced that politics played a role in the crisis. Even the “Civilian Joint Task Force” (CJTF), comprised of youths helping the security forces combat Boko Haram, vented its rage at the political establishment, storming the private residence of the Borno state ANPP chairman, Alhaji Mala Othman, on 1 July 2013 and setting it ablaze, because, it alleged, he is a sponsor of Boko Haram.

Subsequently, hundreds of youths tried unsuccessfully to burn Sheriff’s private residence. They asserted that both Sheriff and Othman supported Boko Haram and had fuelled the crisis. Othman was taken into JTF custody on 6 July and detained for over a month.

Organisational Structure and the Leadership

Boko Haram grew to prominence under the charismatic Mohammed Yusuf, an inspirational speaker who was not a particularly effective leader and had trouble keeping his unruly lieutenants, particularly Abubakar Shekau, in check. The movement never had firm command and control. It is formally led by an amir ul-aam (commander in chief) with a Shura (council) of trusted kwamandoji (commanders in Hausa), its highest decision-making body. The amir ul-aam cannot speak for the group without Shura approval.

In major cities and towns where the group has a presence, a local amir is in charge, alongside a commander who oversees and coordinates armed operations. Depending on his influence, the commander may be a Shura member. He is assisted by a nabin, (deputy), who is in turn aided by a mu’askar, who passes orders from the commander and the deputy to foot soldiers.

Yusuf’s main lieutenants were Muhammad Lawan (Potiskum, Yobe state), Mamman Nur and Abubakar Shekau. Lawan parted ways with him in December 2007, after disagreeing over the ideology and Quran interpretation. He issued an audio recording accusing Yusuf of insincerity and rejoined Izala. Boko Haram attacked his home in a failed attempt on his life during its 2009 uprising. Mamman Nur is a Shuwa Arab born and raised in Maiduguri by Chadian parents. He befriended Shekau while both were doing higher Islamic studies at the Borno State College of Legal and Islamic Studies (BOCOLIS). He apparently introduced Shekau to Yusuf. Shekau is a Kanuri from Shekau village on the border with Niger in Tarmuwa local government, Yobe state. The security forces became more aggressive in turn in September 2012. On 22 September, troops slapped round-the-clock curfews on three cities in the North East, Damaturu, Potiskum and Mubi, killed 36 suspected militants, including a top sect commander and arrested more than 200 in house-to-house raids. Two days later they stormed a Boko Haram enclave in Damaturu, including Shekau’s home. A top commander, Abubakar Yola, alias Abu Jihad, was killed in a shoot-out with troops in Mubi, where 156 suspected members were rounded up. Other factions were neutralised following the capture or killing of their leaders. On 17 September 2012, soldiers shot dead a sect spokesman, alias Abul Qaqa, outside Kano, along with the sect commander in charge of central Kogi and Kaduna states and Abuja. This was a significant blow, a source close to the sect said, because the two were considered its “think-tank”. The killing and capture of top commanders significantly impacted the sect’s eleven member Shura, leading to its expansion to 37. This made it difficult to reach unanimous decisions, with resulting adverse consequences for operations.

Another faction is headed by Aminu Tashen-Ilimi, who led the December 2003 Kanamma uprising alongside Shekau. A University of Maiduguri drop-out, from Bama in northern Borno, he was also among the commanders who led the 2009 Maiduguri uprising. On the third day of that uprising, Yusuf allegedly gave him 40 million naira (then approximately $275,000) to buy arms from the Niger Delta. After Yusuf’s murder, he stayed in Port Harcourt, then relocated to Kaduna, where he reportedly used the money to establish himself as a car dealer. While he is believed to still control a faction, he keeps a low profile.

The most sophisticated faction, Ansaru, was commanded by Khalid Barnawi. Although seen as independent, it is actually a Boko Haram splinter group comprising mostly its Western-educated members. A fifth faction is led by Abdullahi Damasak, also known as Mohammed Marwan.

The sixth and least known faction is based in Bauchi and led by Engineer Abubakar Shehu, alias “Abu Sumayya”. Both Shekau and Ansaru leaders suspected he was a mole, and in early 2012 they agreed to eliminate him. Ansaru men stormed his Bauchi hideout, injuring him and leaving him for dead. However, he survived after treatment in the 44 Army Reference Hospital in Kaduna and a German hospital. He then disclosed Khalid Barnawi’s Kano hideout to the security agencies, which killed him in their August 2012 raid.

The “External” Connection

There has been speculation about potential operational links between Boko Haram and Al-Qaeda. In February 2003, Osama bin Laden named Nigeria as a country to be ‘liberated’. A former US ambassador to Nigeria then warned that armed jihadist groups in northern Mali could spread to Nigeria. Unlike Somalia and the Sahel, however, Nigeria is not geographically contiguous with the Arab world. Moreover, no Nigerians are known to have fought with Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan in the 1990s. Foreign preachers were more likely to go to Nigeria. In 2006, for instance, Mohammed Yusuf was arrested with an envoy of Pakistan’s Tablighi Jamaat, Mohammad Ashafa, and accused of sending youth for military training in Mauritiana, Mali and Niger. The two men were released in 2007 by President Umaru Yar’Adua for lack of evidence.

Boko Haram uses Banki as its main entry point to Cameroon and has established camps on Lake Chad islands including Madayi and Mari. Yet its members have continued to concentrate their violent struggle within Nigeria. A greater military involvement of Cameroon, Chad and Niger could incite the movement to open another front. In May 2014 suspected Boko Haram militants attacked a police station in Kousseri and a camp run by a Chinese engineering company in the far north of Cameroon. However, it is not clear whether the organisation has the capacity to sustain conflicts on multiple fronts. In northern Mali, the success of AQIM and MUJWA (the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa) was clearly a source of inspiration for Boko Haram.

In December 2011, it mounted a failed attack on Diffa in the Republic of Niger, to demonstrate that Borno jihadists were also capable of going beyond borders.

It is possible that some Boko Haram members even went to fight in northern Mali in 2012. There were reports of Nigerians in Timbuktu and Gao, with a local witness claiming that 200 members joined AQIM.

However, with the exception of a few witnesses including Canadian diplomat Robert Fowler, who was kidnapped by AQIM in the Republic of Niger in 2008 and who saw a Nigerian while being held captive, it is difficult to find hard evidence of a massive arrival of Boko Haram combatants in northern Mali.

Contact between individuals to acquire weapons or train bombers is very likely. But this does not mean coordination or even friendly cooperation. The French Army found no trace of Boko Haram when it launched Operation Serval in northern Mali in 2013. Abubakar Shekau never pledged allegiance to Al-Qaeda; in turn, he was disregarded by a movement that focuses more on Christians, ‘Crusaders’, Jews and foreigners. The doctrine of Yusuf was quite different from Osama bin Laden’s in this regard. As for Abubakar Shekau himself, he appears to be too unstable, impetuous and unreliable to attract professional terrorists, even if he does now control territory, a prerequisite for Al-Qaeda support. Responses to the crisis have suffered from mistranslated and misquoted video footage.

The fact that in 2010 Abubakar Shekau and AQIM emir Abdelmalek Droukdel both expressed sympathy and solidarity for their struggling ‘brothers’ in northeastern Nigeria or northern Mali does not prove much, one Boko Haram communiqué from 2010 having been put on AQIM’s media platform.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!