By

Gulcin Newby Kennett

In her Quarterly article, ‘Mirrors without memories: Truth, History, and the New Documentary’, Linda Williams raises some stimulating arguments regarding documentary filmmaking.

She starts by challenging Oliver Wendell Holmes’ metaphor of the photograph (and the moving picture) as a “mirror with a memory.” Williams claims that the manufactured (manipulated) image is no longer an accurate witness to the objects, persons or even the events it captures since modern technology can make the cameras lie as becomes necessary.

Williams quotes from Fredric Jameson, a critic of postmodernism, to establish that in our image driven society, images themselves in time become separate entities, completely disassociated from the reality of a past that they were supposed to represent. This loss of connection results in a nihilistic lack of faith in what once seemed as the ultimate objective truth: the picture.

Then, if there is really no truth in pictures, where does this leave those who attempt to capture the reality of the moment as it unfolds just like in many examples of cinéma vérité? Williams believes that this can only be attained if the filmmaker can let go of the notion of a singular mirror (his/her camera) that is telling the absolute truth, and allow for the possibility of many mirrors fading into a disappearing horizon, each reflecting a relative version of the same reality. This, she calls the self-reflexive film. As successful examples of this genre of film Williams offers Errol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line (1988) and Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985), both of which stand out in their “unprecedented popularity among general audiences, and their willingness to tackle often grim, historically complex subjects.”

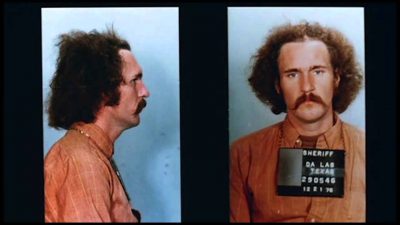

Of these two films, Williams particularly mentions Morris’ The Thin Blue Line as the prime example, because of the fact that even though the film depicted events in an inaccessible, forever lost past, it actually had an impact on the present by helping the release of Randall Dale Adams, who was wrongfully convicted and sentenced to life in Dallas, Texas.

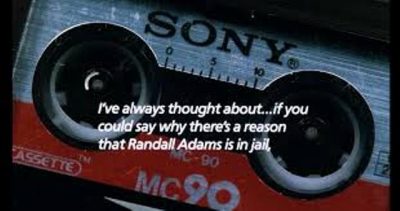

The confession at the end of the film by a key prosecution witness actually reveals the innocence of the accused man and the state (and the police) conspiracy to punish this scapegoat drifter rather than go for the real murderer. This, Williams argues is exactly what cinéma vérité had been striving to achieve in its hollow and forced quest for mirroring the truth. Yet, Morris pulls it off by way of stylistics slow-motion docudrama reenactments of different versions of the murder story as told by different witnesses in between interviews with all the involved parties. Highly dramatic music by composer Philip Glass accompanies these reenactments.

The success of the Thin Blue Line, quoting Williams, rests in the fact that Morris “working in a documentary form now eschews cinéma vérité as a style, stylizes his own hypnotic reenactments and never really offers any of them as an image of what actually happened.” Of course, while doing so, he strategically gives the viewer some truths while withholding some others. Yet, this does not discredit Morris’ approach to the story, because the present time interviews of the certain characters betray their guilty past in the eyes of the viewer, forever.

According to Williams, “[I]t has become an axiom of the new documentary that films cannot reveal the truth of events, but only the ideologies and consciousness that construct competing truths – “. To a great extent, this can be observed in Shoah, Lanzmann’s documentary about the Holocaust as remembered in the words of those who lived through it. In one of the controversial scenes of the film, Lanzmann stages a scene of a homecoming of a Polish Jew at the steps of a Catholic Church, in which the seemingly friendly Poles reveal their belief that the Jews were slaughtered, not because of racial hatred but because of what they had supposedly done to Jesus Christ over a thousand years ago. Upon hearing this present day testimony, captured in the style of cinéma vérité, the viewers become aware of the guilt or at least the complicity of the seemingly friendly Polish peasants in the crimes against the Jews during the war.

In both The Thin Blue Line and Shoah, the directors do not attempt to recreate a past with full exact detail to show exactly what happened and who was guilty. As Williams observes, “the past events examined in these films are not offered as complete, totalizable, and apprehensible.” Instead, these films try to capture the “reverberations and repetitions” of the long gone past events into the present day, and allow the viewers to see for themselves the traces of the guilt through often inconsistent fragments of reality.

In this type of documentary these fragments become the mirrors that reflect the multiple facets of past events, without seemingly favoring one over the others as the absolute truth , but letting the audience decide who is lying and who is telling the truth.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!