By

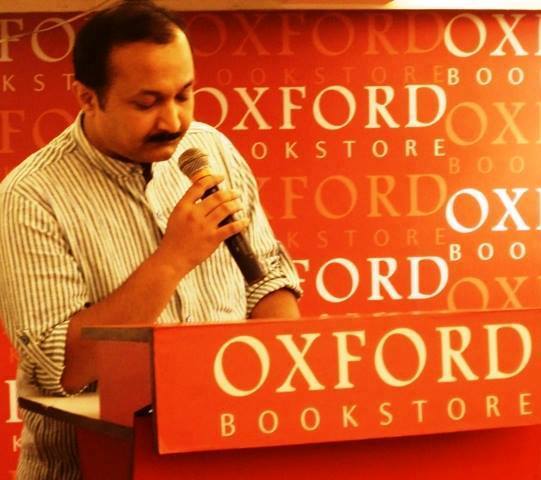

Kaushik Acharya

There are plenty of Sanskrit texts like Pancatantra, Hitopadesa, Abhijnanasakuntalam, etc, and even The Ramayana, The Mahabharata, two immensely popular Indian epics, which have been successfully translated into several other languages down the ages.

If we observe carefully we can understand that there are hardly any Indian or foreign literature that have been translated into the Sanskrit language. Does Sanskrit literature refuse to receive inputs from texts written in other languages? We have no viable answer here. We probably have never considered or tried to include them in Sanskrit literature as we think Sanskrit bears traditional glory, and an attempt to include foreign texts will only weigh it down and above all, we don’t just need to include those texts into Sanskrit literature. People often question the flexibility of Sanskrit language. A language or literature can exist freely if it is flexible, welcoming and accepts wisdom from external sources. Sanskrit literature, perhaps, lacks in these attributes.

It is high time we accentuate the treasures of Sanskrit literature. Students who are studying the subject should necessarily be aware of contemporary world literature. Of late I have translated a few poems by well-known Indian English poet, Kiriti Sengupta, and I have rendered them into Sanskrit owing to their spiritual connotations. Let me cite both the original and translated versions here and my thoughts on them.

sampasya

trisu netresu durgayah trtiyam tu

adyaiva aparivartaniyam asti,

ayam tu ardha unmuktam unmuktam va

loke avalokyate

visaye’ smin vigrahakara api udasinah santi,

pasya—

te parthivanetrayoh vivartanam krtavantah yuge yuge,

na tu trtiyam

Keep an Eye

Among those three eyes of Durga

The third one has been the same

Over the ages

It has been kept open

Full or half

Sculptors never bothered

They have been experimental

Only on her earthly eyes

[The Earthen Flute, page 15]

Sanskrit literature basically deals with religious and spiritual subjects and themes. We can analyze the world through visions, one is practical and the other is spiritual. The saints usually describe the reality of life through their spiritual vision, which is impossible through the earthen eyes, but the third eye, otherwise known as the inner eye, plays a pivotal role in envisioning the self.

In some traditions such as Hinduism, the third eye is believed to be located around the middle of the forehead, slightly above the junction of the eyebrows. In this poem, “Keep an Eye,” we become aware of the fact that the third eye has remained the same down the ages, like the third eye of Hindu goddess Durga. Even the artists and sculptors have tried their hands in other aspects of the deity, like dress, color, etc, except the third eye that represents spiritual vision or a symbol of self-realization.

I think the poem is extremely relevant in Sanskrit literature not only for its translation-value, but mostly for its spiritual tone and wisdom, which are integral of said literature.

jatharah

pratikampanam prthivyah anubhuyate maya,

mataram prati aham samyak-prayatnaya

asamarthah abhavam

punah mam jatharastham

kartum tasyah svadhikarm vartate

janami adhunapi,

sa prabhuta-yatnasila bhavisyati

yatha sa purvam eva krtavati

bho jagata! yady api parthiva-lopaya

bhavantah alocitovantoh bhavanti,

mata hi kevalam prasavapidavagantum saknoti

Womb

With every earthquake I realize

I have failed to express

Much attention

To my Mother

She has a right to take me into her

Again

I know she will take

Enough care

As she took before

World, you may comment on material loss

Only the Mother understands her rupture pain

[The Earthen Flute, page 17]

We are attached to our mothers who often become a subject of description in literary works and Sanskrit literature is no exception. Mothers are not only the ones who give birth, they can raise children to be called a mother. Poets and philosophers frequently consider the earth a mother. In “Bhumi Suktam” of Atharvaveda we find the earth as goddess.

mata bhumih putro aham prthivyah [Atharvaveda 12.1.12]

[The earth is my mother and I am her son]

Since Vedic period the earth has been worshipped in connection with its various utilities in life. Mother earth takes care of us in many ways; we are born and brought up on the planet, we live, and finally, we die here in the earth.

In this poem, “Womb,” we can realize our responsibility to Mother earth. But, humans turn selfish as they fail to acknowledge the contributions of Mother earth to their lives and with modernization of human race they tell upon her with every passing day. Even the mother has a right to revolt from being suffered by the indifference of her children who receive much nourishment in the womb for months. In this poem we understand the reality of extreme deception that affects Mother earth which the sages upheld in Vedic hymns and prayers.

vedhasah toranmargam

prarthanasu pranah santi,

ta anirvacany anubhutih

tasu asmakam tarsah lavate

suraksitam asrayasthalam

evam parthivanandaya samrddhilavaya ca

vayam prayah bhitasantrastah bhavamah

saa hi mantrita bhavanti nimilitakse,

vayam ca bhutacakitah san jivanadhanam kurmah

anivarya-mrtyuvat ko’pi virit devah

samyak avirbhutah bhavati

Gateway to God

Prayers carry lives within

They are expressions

Our desires take refuge in—

For all worldly pleasures and fulfilment

We remain scared, perhaps

Wishes are chanted with closed eyes

And we continue to live being frightened

Like an inevitable death

An enormous God steps in

[The Earthen Flute, page 25]

The Vedas are the first texts in the library of mankind. In them we could find the tradition of holy mantras which were chanted to please the gods and goddesses. The concept of God came from the destructive patterns of Nature, and from a strong belief of her supernatural prowess like fire, storm and thunder, drought and flood, etc. In Rigveda the sages practiced Vedic hymns for a better life and afterlife.

In this poem, “Gateway to God,” we find a characteristic human behavior during prayers. We keep our eyes closed being frightened of both God and death. Death is not necessarily a loss of life, it can be described as an abolition of dreams and desires. During Vedic times the sages used to reflect on their inner realizations and renounce worldly pleasures to achieve God. They were barely afraid of anything under the sun, except for their fear of being detached to their spiritual practice. Austere practice opened up their inner eyes that envisioned the futility of earthly fulfilments. “Gateway to God” is an original masterpiece of world literature and Sanskrit literature as well.

[a]kalamanudanam

gurubharikah kaksapavanah

pita putramahuya asandamasou

datum aicchat

mata uvaca: “siddhantam idanim asamicinam adhuna,

sighram idanim gurubharam putraya,

yaccha mama putram plabitum.”

pita na jnapitavan adyapi paricare, yat—

ayacanam tasya abhyanujnatah adhipurusena,

sa ca avakasaya anumanyate

[Un]Timely Grant

The air smells heavy

Father calls up his son

He wants to offer him

The chair

Mom says, “It is too early for him,

Let my son keep afloat!”

Father is yet to inform family,

Boss has approved his prayer

and he is allowed to leave.

[The Earthen Flute, page 57]

Since time immemorial a father plays the main role in his family. He acts as the chief; the role of a leader. The growth and prosperity of a family depends on its leader. In ancient India a father often ruled the family from being the sole provider. In this poem, “[Un]Timely Grant,” we realize the importance of the provider in a family. The following Sanskrit verse depicts the essential qualities and duties of an ideal father:

annadata bhayatrata, vidyadata tathaiva ca

janita copaneta ca, pancaite pitarah smrtah

[Chanakya Niti]

Who could be considered a father? The one who feeds you or provides food, one who keeps you away from fear, one who educates, one who caused the birth (biological), one who performs the sacred thread ceremony. These attributes qualify one to be called a “father.” The most famous verse comes from The Mahabharata:

pita svargah pita dharmah pita hi paramam tapah

pitari pritimapanne priyante sarvah devata

[My father is my heaven, my father is my religion, and he is the ultimate penance of my life. If he is happy, all gods are pleased].

In “[Un]Timely Grant” we can figure out a father of contemporary era. But the basic pattern is the same as before. A father works until he retires, but he continues to dominate the family. As he approaches retirement, the father offers the chair (position) to his son, but a mother rarely considers her son grown up and declines her husband’s proposal. In reality we love to be governed by our fathers or father-figures and this stunning, short verse succeeds to grab the attention of the readers.

samaya sramam

kascid prstah kimaham

vidyamanam abhasanm abhijanami…

atha anubhabami,

katham tu manusya anubhavanti samah?

iyamavastha kim purnah ravabhavah?

kim rabakarah daivayogad api samam ahvayati?

sangharsinah bhavamah vayam ekavastha praptaye,

yatra iyam murali kadapi na sabdayate-

tatra vayam svasarahita’pi samitah bhavamah

aikantika-samvaditah bhavisyamah ca vayam

visvakarakamadhye

api ca parthivamilanavasane nrpocita niravata virajate

Struggle for Silence

Someone inquired if I was aware of existential silence…

But then, how do people perceive quietude?

Is it a state of complete absence of noise?

Does clamor invite peace, by any chance?

We are, perhaps, struggling to achieve a stage

Where the flute won’t sound anymore;

We will remain breathless, but relaxed

And in complete harmony with the creator!

Quiet grandeur prevails over

The pinnacle of worldly communion

[The Earthen Flute, page 59]

Life and afterlife have secured a major part in Vedic philosophies. In The Vedas, there were three stages of life: student-ship, household-ship and retirement. During Upanishadic era, Hinduism expanded to include a fourth stage of life: complete abandonment. In Indian philosophy, silence, which has a vibration of its own, refers to peace of mind, inner quietude, Samadhi and absolute reality. The ancient texts insist upon proper understanding of silence by experiencing it through complete control of breath and tongue that leads us to a state of eternal bliss. People may refer it to as “death,” but we all are approaching to this ultimate stage through the journey of life.

This poem, “Struggle for Silence,” bears a deep spiritual undercurrent. Here Sengupta questions if anyone is aware of the ways to achieve inner peace that we long for. But then, he answers on his own. Sengupta emphasizes on being “breathless, but relaxed,” a state that is achieved only by the yogis. Yoga, as The Gita suggests, refers to the actions that enable one to unite with the Supreme Being, otherwise known as God.

We can relate this poem with the Vedic and Upanishadic thoughts about ultimate silence: “Samadhi,” or “death.” We are headed towards the former through yogic practice or towards the latter through our usual course of life. Death is always the ultimate, worldly reality of life and it is evident in philosophy as well as in literature. This poem makes a special place in the sea of wisdom and claims to be included in Sanskrit literature by its inherent merit.

Reference:

Sengupta, Kiriti: The Earthen Flute, Hawakaal Publishers [Calcutta]; First edition, February 2016, ISBN-13: 978-93-85783-58-6

Kiriti Sengupta

Kiriti Sengupta is the author of the best-selling trilogy: My Glass of Wine [novelette based on autobiographic poetry], The Reverse Tree [nonfictional memoir], and Healing Waters Floating Lamps [poetry]. He is a bilingual poet and translator in both Bengali and English. Sengupta’s other works include: The Earthen Flute [poetry], A Freshman’s Welcome [a chapbook on memoir with literary critique], My Dazzling Bards [literary critique], The Reciting Pens [interviews of three published Bengali poets along with translations of a few of their poems], The Unheard I [literary nonfiction], Desirous Water [poems by Sumita Nandy, contributed as the translator], and Poem Continuous – Reincarnated Expressions [poems by Bibhas Roy Chowdhury, contributed as the translator]. His poems have been widely anthologized, both nationally and internationally in Kritya, Taj Mahal Review, Labyrinth, Grey Sparrow Journal,Dukool,Wilderness House Literary Review, among other places. Reviews of his works can be read on The Fox Chase Review and Reading Series, Muse India,Red Fez Magazine,Word Riot, and in The Hindu Literary Review, to name but a few. Sengupta has also co-edited four anthologies: Scaling Heights, Jora Sanko – The Joined Bridge, Epitaphs, and Sankarak.

I heartily congratulate Kaushik Acharya on his translation of some of Kiriti's poems into Sanskrit. With my little smattering of Sanskrit, I have liked the translation. Now on a couple of generalisations made by Kaushik, may I beg to differ? It's not that Sanskrit refuses other language literatures to be translated into it, nor is it that it has its limitations preventing such work. In fact, Sanskrit has the power of coining any number of new terms, because of its scientific and strong etymological roots. The problem is not that of Sanskrit but of the lack of competent translators. The initiative has to be taken by scholars who are equally proficient in Sanskrit as well as the source language concerned. In fact, it is the other way round. Since Sanskrit is a treasure house of various aspects of learning, the works in it have been extensively translated into many foreign languages. However, the politico-historical factors have reduced the importance of Sanskrit – sadly, in its home country, and with that the number of serious Sanskrit learners has steeply dwindled. Paradoxically, Sanskrit is being learnt across the globe by quite a good number of enthusiasts. Most of the good literatures have a universal appeal because of the commonality of human nature and emotions, and it is always easy to translate such things into any language. It is interesting to note that the United Nations’ Charter “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” was translated into Sanskrit by Dr Jitendra Kumar Tripathi, Secretary of the Lucknow-based Akhila Bharatiya Sanskrit Parishad. And there are many enthusiasts who are rendering pop songs in Sanskrit. There is even a Sanskrit pop band in Bengaluru. If nobody is translating other literatures into Sanskrit is mostly because of the stark fact that the Sanskrit learners and readers are very few. If somebody still does, it is only for his own satisfaction, or out of commitment to the language, or out of an ad hoc demand. Hence the need of the hour is to encourage, widen, popularise Sanskrit studies – which are a cornucopia of several things both liturgical and secular. Organisations like Sanskrita Bharati are doing a yeoman’s service in this direction. And all Sanskrit lovers should encourage and support them. At least we have news in Sanskrit on AIR and Doordarshan. It could be expanded into live debates over news and current affairs. In the light of all this, I once again congratulate Kaushik Acharya because he is among the not so many Sanskrit scholars that are available with a mind to bring the beauties of Indian vernacular and foreign literatures into Sanskrit. I wish him all the best and hope that he would think of translating at least a few of the Western classics into Sanskrit and find suitable avenues toward it. And my congrats to Kiriti on being translated into the world’s most ancient language.

Thank you so much for reading and commenting on my work, Sir. I agree with the points you have discussed. Thanks again for being an inspiration.

Thank you so much for this enlightening piece, Kaushik! Thanks to Tuck Magazine.