The bleak and unforgiving Labrador wilderness in Canada is as much a place of subtle change as it is fierce rigidity; it is a contradiction of a land defining its people, the people’s survival depending on their ability to adapt to the land. It is a place of solid, quick decisions made by pragmatic people in a sometimes brutal environment, with the spectre of mortality always looming large in the background of daily life. Living off the land and at the mercy of the cycles and occasional whims of Mother Nature can leave no room for the anomaly or anything that doesn’t fit or make sense, even if the culprit is Mother Nature herself.

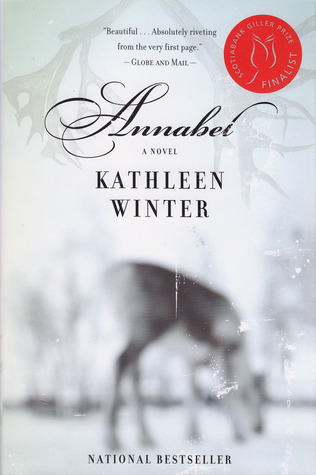

When our children are born our initial concern is that the baby isn’t missing any toes or fingers. We need the reassurance of the attending midwife or physician that everything is fully formed and healthy. Is my baby normal? For Jacinta and Treadway, the birth of their hermaphrodite child, Wayne, would be the source for much contemplation of all the intolerant implications associated with this word. In her novel, Annabel (Grove Press, 2010), Kathleen Winter takes her reader on a harrowing emotional journey through confusion, suffering, understanding and ultimate acceptance that sometimes, normal is nothing more than commonplace, and what we should actually be striving for is what is right individually. To preserve uniqueness and to respect the exception to the rule is, I feel, the spirit of Winter’s novel.

When I asked Winter for this interview, I intended to focus on the novel as an insight into her mind and heart, not only as the creator of this unforgettable story, but also as a woman with her own unique perspective of what life means as it is told through her characters. As expected, Winter’s answers were as introspective, intelligent and graceful as those she places on the pages of her novels.

VBR: While reading Annabel, I pondered if gender affects the way a writer interprets and translates human experience. Do you feel your own femininity was a factor in Wayne’s character development, or were you able to write it from a non-gendered, neutral point of view?

KW: What is my own femininity? I don’t know what it is. Even after writing Annabel. My notion of myself as a woman keeps changing with different phases of my life, according to my age, my relationships, and my mood. Whatever the shape of that notion at any given time, I am certain it was a factor in Wayne’s character and in the book as a whole.

Publisher: House of Anansi Press

ISBN 978-0-88784-236-8

Released June 2010

VBR: It is interesting to note that at the beginning of Annabel, you quote a passage from Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, where she challenges our perceptions of gender. Because you can both be considered trailblazers in terms of questioning the status quo with regard to sexuality, as a writer was there a desire or intention on your part to awaken in your readers an internal questioning and reflection of their own attitudes and beliefs about female or maleness?

KW: I never set out with an overarching goal regarding the work’s effect on a reader’s attitudes and beliefs. My goal is to have the reader transcend loneliness. Even now, at 51, I am daily amazed when I go out on the street and notice how alone most people are when carrying out their daily activities. Even in a crowded city, you can break down the cyclists and walkers and drivers into isolated pools of aloneness. I know not all of them feel lonesome at the time, but I’m just saying everyone is more alone than we probably think. We think we’re the lonely one. But everyone is. Sometimes I imagine cones of consciousness filled with imagery beaming out of the heads of everyone in a crowd. There is a universe inside each of us – what a huge, huge universe in every person. My goal is not to direct anyone’s consciousness in a particular direction; rather, it might be to let us enter community, even if for a little while, and even if the communion is sort of illusory.

VBR: There are subtle nuances of Aboriginal spirituality dancing across the pages of Annabel, particularly in passages dealing with Wayne’s father, Treadway. Are aboriginal myths and spirituality something you have explored in your own life while growing up in Newfoundland?

KW: During my time in Labrador, and in parts of Newfoundland where the Miqmaq live, I have experienced rather than studied the kind of spirit that inhabits the book. For me, it is a spirit very powerful in the land and water and sky. I did see hermaphroditic figures in some pieces of Labrador art by an aboriginal artist, and I have listened to the songs sung by an Innu father to his children in a tent at night, and some of these things filtered too into the book.

VBR: Other than Derek Warford, there are no villains in Annabel. He is the one character in the book with less emotional depth and you don’t linger on the finer points of his repugnant personality. One could say he is the perfect stereotype of a sexual predator, very effective in engaging the ire of the reader. When writing your stories, are there certain characters such as Derek Warford that are so removed from your own morality that they are emotionally difficult for you as a writer to create and inhabit, or are you able to leave your personality behind when you are immersed in the act of writing, thus ensuring the integrity of the story?

KW: I’m not able to leave my personality behind at all. I’ve thought about Derek Warford since I finished the book. I’ve thought about what I did to him, or did not do, which made him different from my other portrayals as you say. I could go into his character and write about him, but I chose not to for this story, because I got carried away. Yes, this bullying, and violence, and sad manifestation of what I might call evil, is something I experienced growing up different in a small town. I got out of it alive, and I wanted Wayne to get out of it too, so I focused on him and was sympathetic with him at the expense of sympathy for Derek Warford. I might let other writers work on sympathy for the Derek Warfords of the world right now. It’s too painful for me to have the kind of love for him that I would need to have in order to write him whole. Maybe one day.

VBR: Thomasina, the midwife, was the one stabilizing factor in Wayne’s life, as well as his only access to the world beyond Croydon Harbour. Her purpose in the story was clearly central to Wayne’s maturation and continued connection to his feminine self. Was Thomasina modeled on the women you knew while growing up in Newfoundland, or was she purely a construct of your imagination?

KW: Thomasina was physically modeled after a teacher of one of my family members, and perhaps a bit psychologically modeled after that teacher as well. But most of the inner world of Thomasina, and her motivation, came from my imagination. She is perhaps the most theoretical character in the story. I needed the story to have her power and fortitude and also her depth of perception. Without her, I would not have been able to explore the territory so heartily. I might have been limited to more small-town notions. More redemption might have had to come from the land itself.

VBR: As a mother yourself, you must have pondered what your own response would have been had your child been born both male and female. Was your reaction different upon the completion of the novel than it was before you began to write Annabel?

KW: This is a really hard question to answer. Most new parents are young. I was young when I had my first child. You have rebellion and independence and fierceness when you are young, but is it enough to question medical expertise and the binary gendered nature of your whole society? I don’t know what I would have done if my own child had been born intersex. What would I do now? That is a hard question too. I know what I would like to do, but I don’t know if I would do it. It’s the kind of thing you know only when you really go through it.

VBR: The subject matter of your novel is most certainly a flashpoint for important discussions pertaining to the challenges of transgender youth. Based on this, what reaction if any have you had from the LGBT community since the release of Annabel?

KW: The intersex readers who have read this story have floored me with their generous reading of it, and with their gratitude. People have cried, thanking me for writing it. People carry the book around with them in their purses for company in a lonely world. This is intersex readers and their friends I am talking about. The LGBT community is a bit apart from these other readers and some have questioned how well a cisgendered writer (me) can hope to portray intersex issues. All I can say is that I’m surprised anyone would assume I’m cisgendered.

VBR: You have been showered in accolades and nominated for the most important prizes in literature. Has this level of exposure and your achievement affected the way you approach your writing? Do you feel any pressure to repeat the success of Annabel, or has it liberated you from then need to live up to expectations?

KW: The fantastic thing about the response has been that I’ve suddenly had great numbers of readers and worldwide translation of my work. I’m not sure when I’ll be able to get down to the solitary business of writing my next book (I already have one drafted but I’m embarking on a nonfiction book about the Arctic). Right now I’m in the reading, traveling and research phase of the new work, and I’m hoping I’ll be able to get down to some writing in early 2012. I don’t feel pressure because the new book will be an entirely different project, and I don’t have an advance for it so I don’t have a deadline or anyone looking over my shoulder. That feels good.

VBR: In 1999, the film, “Boys don’t’ Cry” was released. Although the characters and events on which the movie was based were real, the subject matter was very relatable to your novel. Naturally I have to ask if you have contemplated the possibility of seeing Annabel on film or if you prefer for it to remain a book?

KW: I write visually and I would love to see a beautifully made film.

VBR: Lastly, if it is true that each character within a story leaves something behind in the heart of the reader, what would you like Wayne’s legacy to be?

KW: I’d like Wayne’s legacy to be that someone, somewhere, who is about to label another person in any way, instead seeing them in infinite depth and beauty, will stop, think about Wayne Annabel, and ditch the label where it belongs.

Val B. Russell is the managing editor of Tuck Magazine, as well as a freelance writer, novelist and Pushcart nominated poet.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!