By

Cynthia M. Lardner

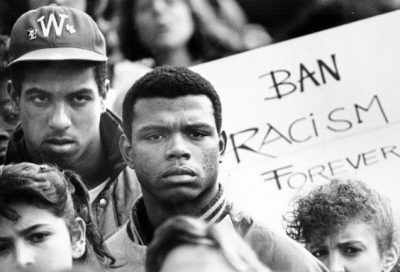

Deep-seated hatreds, prejudices and inequities as to African-Americans have divided America since the days of slavery. The United States has never accepted responsibility and atoned for the vestiges of slavery, with prejudice and the disparate treatment of African Americans continuing to this very day despite civil rights legislation dating back to 1964. For this reason, the United States remains plagued by racial problems.

Almost every day another sad news story appears about an unarmed black man being unjustly shot or, after the fact, the utter unaccountability in the judicial system, giving rise to an unbridled rage now indiscriminately directed at police officers who are being murdered. Historical monuments and symbols from the Civil War, which only commemorate “white history” are being desecrated, while similar monuments and symbols as to the suffering endured by African-Americans are sorely lacking.

Our nation’s leaders – political, religious, educational and civic – at the local, state and federal level must come together to heal a nation that is fractured and hurting. The means is through the creation of truth commissions.

What is a Truth Commission?

A truth commission is a bilateral process between individuals, communities and nations. Truth commissions are founded upon mutual goodwill allowing for open dialogue about past injustices and inequities. A truth commission works toward the releasing of historical hatreds and prejudices so that the process of healing may commence.

When a truth commission is convened painful stories are shared by both the aggrieved and the offended, even if such grievances are historical in nature. In all cases, a sincere apology is offered, whether it be for one’s own offenses or the offenses committed by one’s ancestors. In many cases, reparations are made.

“Cradle to Prison Pipeline”

The shootings of unarmed black men followed by a lack of accountability or redress in the legal system has become an endemic despite efforts by the United States Department of Justice to make some sense out of the senseless. The numbers are bleak:

-

Police killed 102 unarmed black people in 2015, nearly twice each week;

-

Nearly 1 in 3 black persons killed by police in 2015 was unarmed; although the actual number may be higher due to underreporting;

-

37% of unarmed people killed by police were black in 2015 despite black people representing only 13% of the population:

-

Unarmed black people were killed at 5 times the rate of unarmed whites in 2015;

-

Only 10 of the 102 cases in 2015 where an unarmed black person was killed by police resulted in officer(s) being charged with a crime, and only 2 of these deaths resulted in the conviction of the officers involved;

-

The number of blacks killed has included an increase in the number of black female fatalities: and

-

In the first half of 2016, blacks continued to be shot at 2.5 times the rate of whites with less than 10 percent having been unarmed and one-quarter having been previously diagnosed as mentally ill.

“Contemporary police killings and the trauma it creates are reminiscent of the racial terror of lynchings in the past. Impunity for state violence has resulted in the current human rights crisis and must be addressed as a matter of urgency,” stated Mireille Fanon Mendes-France, Chair of the United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent.

The U.N. working group found that in 2014, 37 percent of the state and federal prison populations were made up of black males. It suggested that the U.S. implement reforms, including reducing the use of mandatory minimum laws, ending racial profiling and excessive bail, and banning solitary confinement.

There are other salient statistics. One in five American children live in poverty today, placing the U.S. as having the second highest child poverty rate among developed nations. Among black children the poverty rate approximates 40 percent. Ultimately, poverty creates a lack of hope among young black teenagers who have no expectation of living to maturity. As such, a black male has a one in three probability of being incarcerated. One out of nine black males will be imprisoned between the ages of 20 and 34.

“This is America’s pipeline to prison — a trajectory that leads to marginalized lives, imprisonment and often premature death. Although the majority of fourth graders cannot read at grade level, states spend about three times as much money per prisoner as per public school pupil,” according to the Children’s Defense Fund.

“Arguably the most important parallel between mass incarceration and Jim Crow is that both have served to define the meaning and significance of race in America. Indeed, a primary function of any racial caste system is to define the meaning of race in its time. Slavery defined what it meant to be black (a slave), and Jim Crow defined what it meant to be black (a second-class citizen). Today mass incarceration defines the meaning of blackness in America: black people, especially black men, are criminals. That is what it means to be black,” penned Michelle Alexander, who coined the phrase “America’s cradle to prison pipeline”.

Lynchings and Other Vestiges of Slavery

Lynchings occurred as recently as 1950. Between 1877 and 1950, in 12 southern states, there were 3,969 lynchings, 700 more than research previously indicated, according to civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson, who authored a 2015 report, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror” for the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI).

The twelve states – Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia – have brushed this history under the rug while displaying monikers representative of white supremacy, practices that continue to this day.

The ancestors of many victims, fearing for their own lives, fled to the north. For instance, after a 1912 lynching in Forsyth County, Georgia, white vigilantes distributed leaflets demanding that all black people leave the county or suffer deadly consequences. By 1920 the county’s black population had plummeted from 1,100 to just thirty. This is a form of ethnic cleansing and it was a crime against humanity.

According to the EJI report, “The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s challenged the legality of many of the most racist practices and structures that sustained racial subordination but the movement was not followed by a continued commitment to truth and reconciliation.”

The Necessity for a Truth Commission Unifying America

“It’s difficult to deal emotionally with the history of slavery in America, which is why many whites have chosen not to. Yet it’s imperative that we do, because until we see clearly the line of development leading from slavery to the Civil War to the Ku Klux Klan to the civil rights movement to “benign neglect” to the “prison-industrial complex,” America will continue to misunderstand the real problem. This is not just about how many bullets were shot into Michael Brown. The shots that matter most here are way, way too many to count,” stated spiritualist Marianne Williamson.

The means to deal with this sordid history is through the creation of a truth commissions at the local, state and federal levels to address slavery and ongoing racial injustices and inequities. Both sides have to be willing to come to the table with goodwill and with the hope that they can build a better and more peaceful future for generations to come.

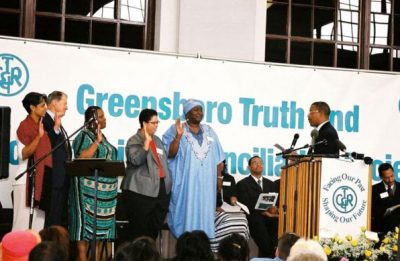

While there have been a few truth commissions emanating from self-organizing community-based grassroots groups, the entire nation must be part of the process. Examples of local efforts include the Greensboro, North Carolina Truth and Reconciliation Commission which exposed the truth of a 1979 massacre of anti-racism activists by the Ku Klux Klan, in which the local police were complicit. It collected testimonies from survivors, Klan members and the police. It culminated in official apologies, public monuments, museum exhibits, a community justice center, a police review board, and anti-racism training for police.

There was also the Mississippi Truth Project, involving the racial misconduct of public officials between 1945 and 1975. It created a safe place where a racially divided community could come together to engage in truth-telling and collective remedial action.

It is now time for America to collectively engage in a truth commission.

“This process of reconciliation is messy and challenging. But it is also a source of hope. Through deep dialogue, truth-telling and taking action to make things as right as possible, we can forge new futures based on the mutual recognition of one another’s humanity. In this way, we can finally leave our past behind us… To move toward a reconciled America, we have to do the work ourselves,” stated advocate Fania Davis.

Due to the complexity of the issues presented and widespread differences between communities, regions, and states, this must occur at many levels supported by not only the state and the federal governments, but also by religious, educational and civic leaders.

Examples of Truth Commissions

While this seems to be a monumental undertaking, there have been two successful truth commissions at the national level; one in Germany and the other in South Africa. They are models for the United States to look to for guidance.

In South Africa truth commissions as to the harm done by Apartheid were created by peacekeeper and statesman, the late Nelson Mandela. In 1994, after Mr. Mandela was elected President of South Africa, he convened a Truth and Reconciliation Commission understanding that the greatest healing would come from three considerations: first, that uncovering the truth about atrocities and injuries that occurred during apartheid was a central component of healing; second, that truth would not be able to be found without the co-operation of the perpetrators; and third and lastly, that the hatred and retribution had to begin to end with one side or the other.

South African author Colleen Scott reflected on the post-Apartheid era, “Reconciliation after war and a hideously grotesque pattern of gross violations of human rights is a matter of creating peace in the present, and of sustaining peace in the future… In and of itself, no Truth Commission can create reconciliation. Much less can a Truth Commission create peace. However, they do create conditions which make reconciliation and peaceful coexistence possible… The TRC has made it possible for the citizens of this country to begin to understand why people participated in such grotesque actions, and it has made clear what must be done to prevent such things from happening again… This was accomplished [by the TRC choosing] to work with a restitutive, rather than a retributive concept of justice.”

In Germany truth commissions have successfully redressed the wrongs committed during Hitler’s Nazi reign. After World War II, Germany fell into a period scholar Lily Gardner Feldman refers to as the “big silence”; their country had been divided and what remained was morally and physically shattered.

“The country was beyond bankrupt as the gruesome details of the Nazis’ systematic murder of 11 million Jews, Poles, Russians, Roma, homosexuals, and others were exposed,” stated Ms. Feldman.

Amidst the rubble, some chose to try burying the sordid past while others started a grassroots movement that evolved into a national initiative. Germany proactively rehabilitated its post-war international reputation by reconciling with Nazi victims and acknowledging the atrocities Germany had committed.

As German Chancellor Angela Merkel recently stated, “We Germans will never forget the hand of reconciliation that was extended to us after all the suffering that our country had brought to Europe and the world.”

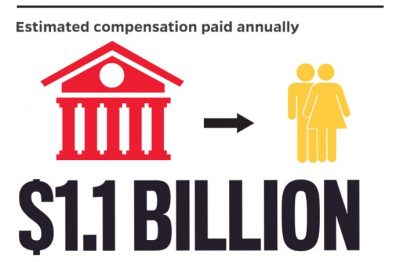

To this day, Germany is still paying an estimated $1.1 billion dollars annually in reparation for the damages it caused.

Conclusion

The United Nations report concluded that “…the United States should consider reparations to African-American descendants of slavery, establish a national human rights commission and publicly acknowledge that the trans-Atlantic slave trade was a crime against humanity.”

If Germany can make reparations for over 60 years, then certainly U.S. state and federal lawmakers can come together to devise a plan for not only supporting grassroots truth commissions, but also for reparations. Reparations can extend beyond monetary payments made to individuals to programs tailored to reduce the “cradle to prison pipeline”, and to the erection of monuments commemorating the black experience from the slavery to the present day.

For instance, Head Start, an early intervention program created by United States Department of Health and Human Services provides comprehensive center-based early childhood education, health, nutrition, and parent involvement services to low-income children and their families designed to foster stable family relationships, enhance children’s physical and emotional well-being, and establish an environment conducive to the development of stronger cognitive skills. Head Start only reaches a fraction of impoverished families and extends only to families with children ages three through five. The program begins too late and ends too soon. In addition, the program fails to provide essential wrap-around services to the families, such a home visits by social workers and food for the entire family.

Programs like Head Start must be re-conceptualized and new programs developed to end inequities and to eradicate the “cradle to jail pipeline”. Such a program has already been developed in the area of counter-terrorism, where the United States has spearheaded the Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) initiative intended to foster environments derailing radicalization. CVE is premised on widespread community involvement, especially that of religious leaders, supported by governments around the world. In the African-American community, its religious leaders, who are highly respected by their congregations, can play an integral role in educating their own congregations as well as starting safe and constructive dialogues with white congregations and interfaith groups.

History books need to be rewritten to tell one history. This has occurred in Europe, where the history books in countries, such as France and Germany, taught differing national accounts of World War II. This is being remediated by a European Council initiative, the European Association of History Educators, referred to as Euro Clio, whose mission statement, in part, reads:

“EUROCLIO has worked in many European countries and beyond on a large variety of issues related to the learning and teaching of history. A special focus has been on countries in political transformation and in particular those with inter-ethnic and inter-religious tensions such as Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Romania, Russia and Ukraine. It also worked in regions that have experienced recent violent conflicts such as Former Yugoslavia, Cyprus, Lebanon and the Caucasus. The work has brought together hundreds of historians and history educators to share experiences, to implement innovative learning about the past, discussing also sensitive and controversial issues and therefore creating new and inclusive historical narratives.”

There also needs to be education in our schools to derail traditional hatreds and prejudices. As Nelson Mandela wrote, “No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

One effort at education, unification and healing is already underway as the Smithsonian Institution prepares to open the National Museum of African-American History and Culture on September 24, 2016. Its website states that “The National Museum of African American History and Culture will be a place where all Americans can learn about the richness and diversity of the African American experience, what it means to their lives and how it helped us shape this nation. A place that transcends the boundaries of race and culture that divide us, and becomes a lens into a story that unites us all.”

The UN report suggested that monuments, markers and memorials be erected to facilitate dialogue, and that “…past injustices and crimes against African-Americans need to be addressed with reparatory justice.” Not only must this occur but the call for the removal of or, worse, the desecration of civil war monuments and artifacts, such as the Confederate flag, must come to an end as they are as much as a part of U.S. history, as that which is lacking, no matter how disturbing.

Former KKK member and white nationalist David Duke just announced that he is running for the United States Congress. Mr. Duke stated, “Thousands of special-interest groups stand up for African Americans, Mexican Americans, Jewish Americans, et cetera, et cetera. The fact is that European Americans need at least one man in the United States Senate — one man in the Congress — who will defend their rights and heritage.” Mr. Duke would continue to fuel racial tensions rather than heal his home state of Louisiana. He is the antithesis of goodwill.

While this paper addressed the African-American experience, truth commissions can also be convened as to other marginalized groups: Native American, Muslim and migrant populations.

Cynthia M. Lardner

Cynthia M. Lardner is a journalist focusing on geopolitics. Ms. Lardner is a contributing editor for Tuck Magazine and E – The Magazine for Today’s Executive Female Executive, and her blogs are read in over 37 countries. As a thought leader in the area of foreign policy, her philosophy is to collectively influence conscious global thinking. Ms. Lardner holds degrees in journalism, law, and counseling psychology.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!