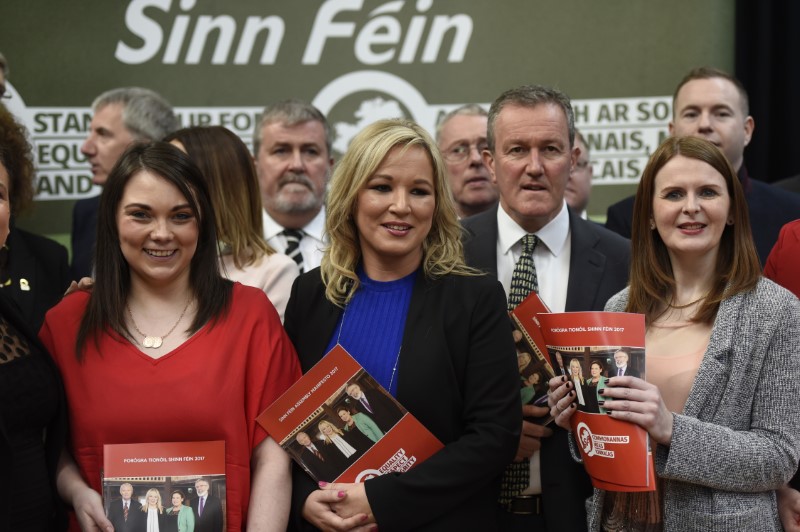

Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters

By

Ian Graham

Acrimonious campaigning ahead of Thursday snap elections in Northern Ireland has increased antagonism between pro-British unionists and Irish nationalists and exacerbated fears devolved power may revert to London for the first time in a decade.

The power-sharing government collapsed in January after Sinn Féin nationalists withdrew support for Democratic Unionist Party First Minister Arlene Foster after she refused to step aside during an inquiry into a scandal around heating subsidies.

Many see the rift as a symptom of a deeper split in the British province between nationalists, balking at the prospect of border posts going up with Ireland after Britain’s exit from the European Union, and Unionists who fear a new push for a united Ireland.

While no one predicts a return to the violence that killed 3,600 people in the three decades before a 1998 peace deal, some forecast a setback in community relations and government paralysis which could weaken the province’s voice in Brexit talks which will determine its political and economic future.

The election “may well be the most dangerous one for unionism since the creation of Northern Ireland,” Foster said in a column in the Belfast Telegraph on Monday, saying that in the event that Sinn Fein come first, they will push for a vote on Irish unification.

“Gerry Adams and Sinn Féin would use an election victory for vindication of their position that the border between the UK and the EU should be the Irish Sea,” she said referring to the president of Sinn Féin, the IRA’s former political ally.

Despite pleas from Dublin and London to avoid a further souring of relations, the two parties have used the campaign to rally their sectarian bases.

Sinn Féin has warned of DUP “arrogance and contempt” towards Catholic nationalists and said on posters that Sinn Féin is the only option for those who “really want an Irish Republic.”

Under the peace deal, elections lead to coalition talks between the largest unionist and nationalist parties – almost certainly the DUP followed by Sinn Féin.

But throughout the campaign Sinn Féin has repeated preconditions that the DUP says it will not accept.

Sinn Fein leader Michelle O’Neill (C) stands with other candidates at the launch of the Sinn Fein campaign for the 2017 Assembly election, in Armagh, Northern Ireland, February 15, 2017. Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters

As well as insisting that Foster temporarily stand aside as DUP leader, Sinn Féin wants Northern Ireland to set down rights for Irish language speakers into law.

Foster, whose father narrowly avoided being killed in an IRA shooting, insists she will never accede to new Irish language legislation, saying of Sinn Féin’s demands that “if you feed a crocodile, it will keep coming back and looking for more.”

Providing Polish translations of official documents would be more appropriate, she said.

“There have been a lot of insults exchanged but other than that there will be no change,” Brian Feeney, a Belfast-based historian and political commentator, said of the elections.

“Sinn Féin walked away and they are not going back into an executive this year,” he predicted.

While the return of Northern Ireland’s 1.8 million people to direct rule from London has long been anathema to Irish nationalists, some commentators have noted that this could deprive the DUP of a voice during Brexit negotiations while Sinn Féin can use the Irish government to lobby its interests.

Smaller, non-sectarian parties campaigning to end the Catholic and Protestant affiliations that have kept the link between religious and party support higher than anywhere in Europe, hope to build on gains a year ago. But no one expects them to impact the balance of power.

Many voters say they are fed up with sectarian bickering and plan to stay at home in a province where turnout has fallen at each of the last four elections to the lowest level among the United Kingdom regions.

“It’s just a bunch of old people, out of touch with the current times, living in the past and fighting over problems that don’t exist any more,” said Samuel Hamilton, a 29-year-old supervisor in a fast food restaurant who does not plan to vote.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!