By

Cecilia Sandroni

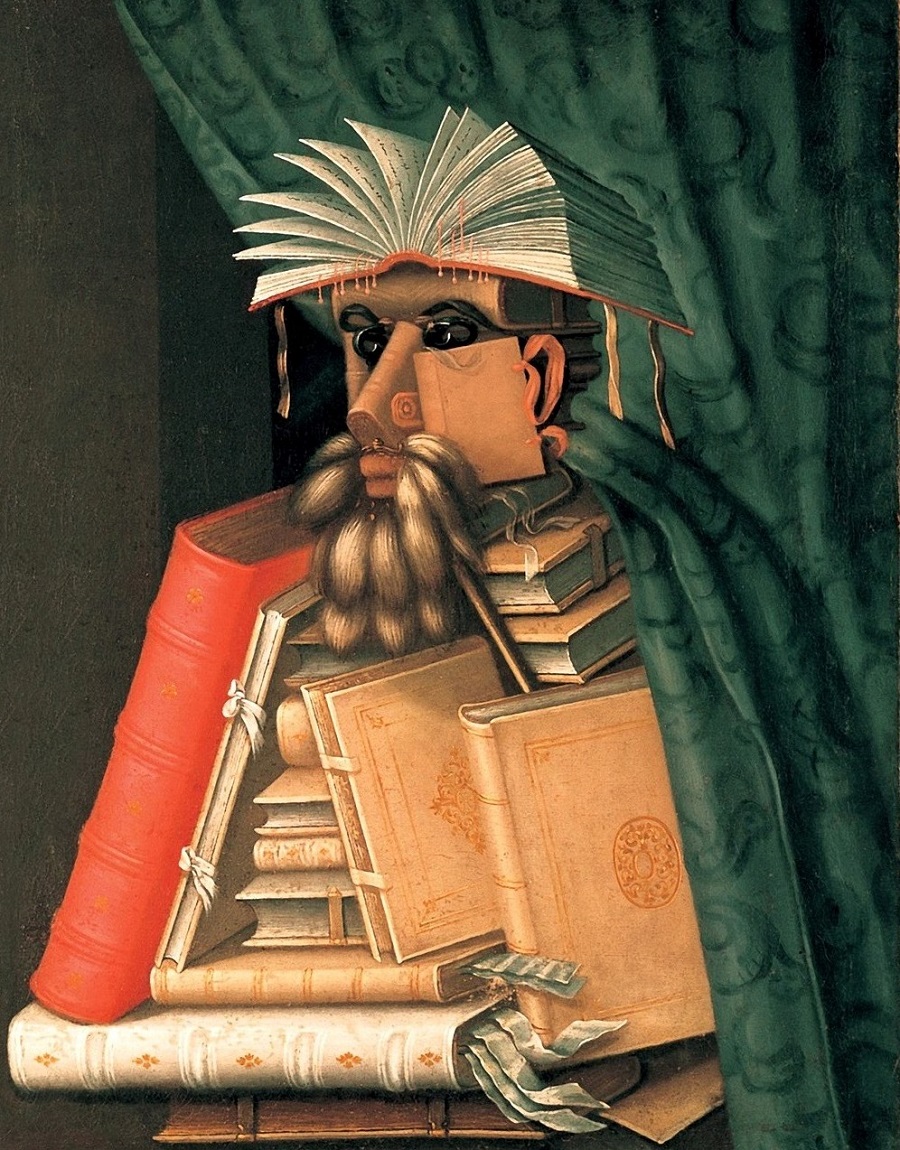

The work of Italian Mannerist painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526-1593), known as Arcimboldo, is present for the first time in Rome in a major exhibition in Palazzo Barberini until February 11. The show features approximately 20 works by the artist famous for his imaginative portrait heads made of objects such as flowers, fruit and animals that made him one of the protagonists of 16th century Lombard culture.

The success enjoyed by Arcimboldo’s composite heads is linked to an idiosyncratic phase in the history of collecting. Following the discovery of the Americas and the opening of trade routes to the Far East, animals, plants, minerals, and artefacts, the like of which had never been seen before, began to reach Europe, stimulating an almost morbid interest in the exotic, the extravagant, and the monstrous.

The second half of the 16th century saw the appearance in many European cities of stunningly eclectic collections displaying human-made objects beside scientific finds to stunning emotional effect; in fact, the literal meaning of the term Wunderkammer is “chamber of wonders”. Emperors Maximilian and Rudolf II both built up outstanding collections of curiosities in Vienna and Prague.

As the exhibits show, natural objects were presented as a precious part of an elaborate display: there were flame-like coral branches, coconut shells nestling in gilded filigree, animal horns mounted on ebony bases, ivory turned on the lathe to create stunning effects of translucency, and much more. Zoological specimens and stuffed animals stand side by side with bronze statuettes imitating snakes and other reptiles.

The art of creating highly realistic naturalistic illustrations developed in Bologna thanks to the efforts of Bolognese naturalist, Ulisse Aldrovandi. Arcimboldo also participated in the illustration of volumes of zoological and botanical cataloguing promoted by this scholar.

Aldrovandi’s interest in the Gonzalez family also stemmed from this fascination with the unique features of nature; in fact, the members of this family, which was celebrated all over Europe, all suffered from congenital hypertrichos Arcimboldo’s composite heads are among the most unmistakable creations of 16th-century Europe. While it is hard to identify specific figurative precedents in the field of painting, there are interesting examples in the fields of engraving and in the applied arts, including medals and ceramics, many of which giving prominence to the phallic aspect.

There are also prints depicting anthropomorphic landscapes where natural elements are combined to form giant faces. One of them is based on a drawing by Arcimboldo.

Such images played a key role in the fierce religious debate raging in the 16th century: Catholics and Reformers often called upon the weapon of satire and caricature, using deformed or monstrous portraits often including heavy sexual allusions or revealing a completely different figure when turned upside down as in a number of paintings by Arcimboldo.

Cecilia Sandroni

Cecilia Sandroni is a member of the Foreign Press in Rome, in addition to being an expert of international relations in communication. Her skills range from film to photography with a passion for human rights. Independent, creative, concrete, she has collaborated with major Italian and foreign institutions for the realization of cultural and civil projects.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!