By

Casey Dorman

I once told Kiriti Sengupta, in an email, “You epitomize the free thinker who respects tradition—a combination rarely seen.”

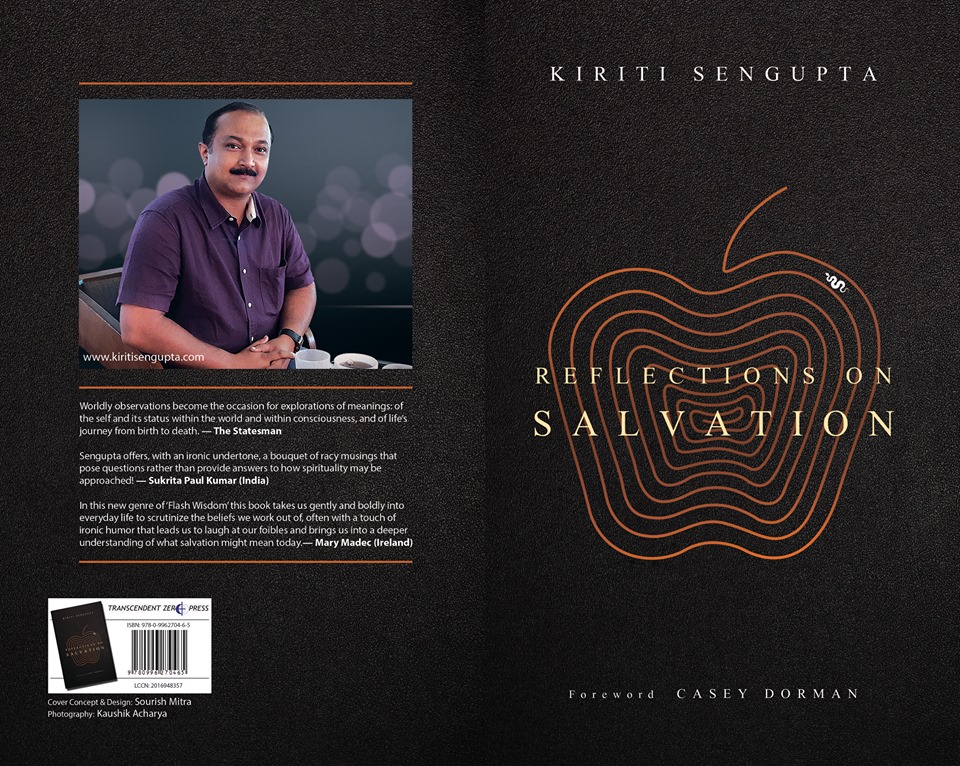

I had just finished reading his book, Reflections on Salvation, for which I later wrote a foreword. The small book is a collection of, in the words of Irish poet, Mary Madec, “flash wisdom,” a description I find apt for a series of short observations, mostly centering on the topic of renunciation of the world vs. attachment. Without being harsh or insensitive, Sengupta questioned both the value of unattachment as a goal and its practice in those who identify themselves as religious. I imagine that it was a somewhat brave stance in a country where such a concept is hallowed in tradition and in which religious people, such as monks, are probably respected for their lack of worldly attachment. It is not a concept foreign to a Westerner, such as myself, but it is not generally valued in the West, except as an antidote to excesses in valuing material success.

I’m not familiar with Indian literature sufficiently to be able to say how much of what Sengupta writes breaks new ground, but, even with my background of reading experimental and iconoclastic literature from Western writers, I have been impressed with his stylistic freedom and his questioning attitude.

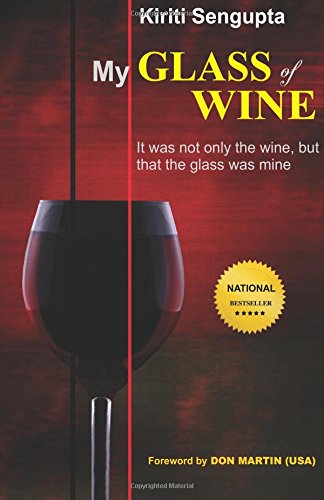

The first book of his that I read was My Glass of Wine. I was expecting a book of poetry. Instead what I found was a book of personal reflections, written in prose and augmented by short verses. This combination of prose and poetry used to complement each other was something new to me, although Dustin Pickering’s review of the book in Lost Coast Review, suggested that it might be “a new form of literature being written by Indian writers.” Whether or not the style is inventive, I found it refreshing. The poetry expressed an image-laden reflection of what was said more directly in the prose. To those readers who have a short attention span for poetry, in the opening piece in My Glass of Wine, the author states that he is hoping to reach a wider audience than typically is attracted to pure poetry. In his words, “I think poetry should not read too abstract! It can be made accessible and enjoyable as well.” His book defies classification by genre, a point he appreciates quite well. As he says, “This is a book written in the English-language, and in several ways. Look, by categorizing a book we actually classify the readers.” Rather than do this, he invites all readers to join him in the experiences he includes in his writing. This is just one example of Kiriti Sengupta’s democratic attitude: he is sharing his experiences and observations with the many, not just the few who consider themselves literary enough to read poetry.

I don’t read the Bengali language, so I am thankful that the six books by Kiriti Sengupta that I have read have all been written in English. This is apparently a point of contention among Indian writers and he gives no apology for not writing in Bengali. Sengupta says: “Writing in English is no sin, nor is it a lesser offense. This is just a matter of personal choice.” What he does insist on is that he is writing as “an Indian [Bengali] author. I’m a born Bengali and if my writing does not ooze the essence of Bengali culture and traditions, I’m only ignoring my being on the earth.” This pushing against boundaries, examining whether they are legitimate or not, is a trait that is illustrated in all of his writing. His religion is obscure to me. He talks of being baptized as a Christian, but also of his Hindu heritage. His description of his Christian baptism as a young adult is ingenuous and a little humorous. In response to drinking red wine as part of a Christian ritual, he reflects upon the role of wine in Hindu Tantric worship. His acceptance of religious meaning and his eagerness for experiencing religious practices appears to be open and eclectic, a rare find in any human.

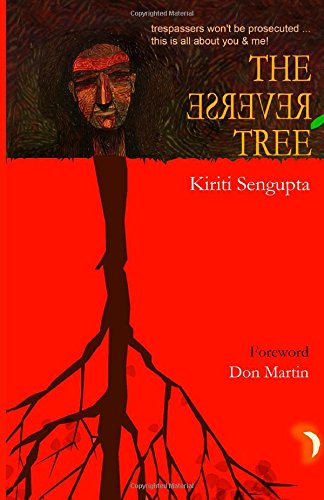

The Reverse Tree is one of Kiriti Sengupta’s most interesting books, at least in my opinion. It is a series of observations revolving around the subject of male identity, or, more broadly, about the many aspects of humanity existing in a single person. The essays and poetry are revealing and are often unflinching in their honesty and their nonjudgmental stance. Particularly, I was impressed by the awareness of and admission of both male and female components in a full personality. In his essay “Crisis” Sengupta describes meeting a transgender person, Lara, who was enduring both a physical and emotional crisis in her life (she was a born-male who was in the process of assuming a female identity). Sengupta’s description of his interaction with her is empathic, curious, accepting and contains no hint of censure or judgment. Neither is there any fear of his own sexuality becoming compromised by his interaction. In a word, he sees Lara as a human being going through struggles as any human being does, though the content of the struggles might be different. His poetry acknowledges the male and female sides to a single personality—“I’ve my own equation of love/my he throbs in fire/while my she is coy.” In response to questions of the wisdom of writing a poem such as this, he writes, “Ah! I admit that the poem I cited above has a blend of both sexes in a single frame, and although a poem is essentially omni-gender, I won’t mind if my readers mark this poem as ‘bisexual’.” He goes on to cite the presence of a third sex as a category in the Vedic literature. He discusses the presence of laws against homosexuality in India and remarks “I wonder how such a law can possibly exist in the world’s largest democracy!”

The Reverse Tree also touches upon racial discrimination, discrimination due to skin color, and attitudinal biases that interfere with moving from one culture to another. One of my favorite of Sengupta’s poems is as follows:

they said you were black

they knew they were white

they loved their eyes

the immigration officers were curious

I pulled my sleeve up to the elbow

showing them the mark

they grinned…

and I said

this has been the Nelson Mandela patch

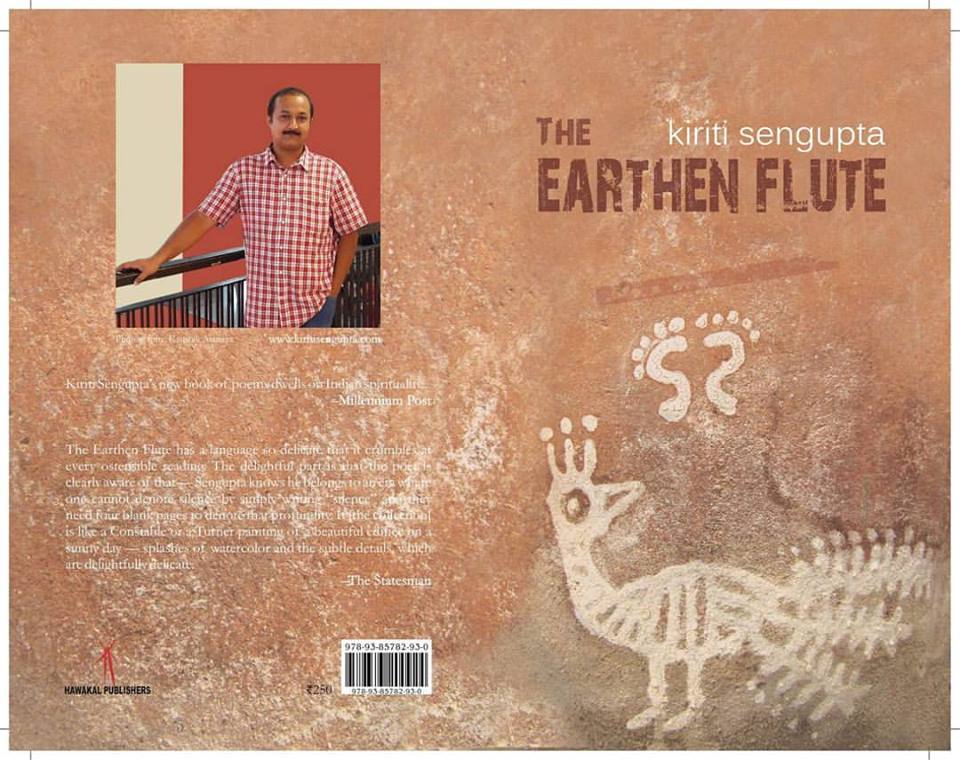

Two of Kiriti Sengupta’s books that I have read are all or mostly poetry. These are Healing Waters, Floating Lamps and The Earthen Flute. Despite having been editor of a literary review that published mostly poetry for several years, I am a poor poet and a poor judge of poetry. But Sengupta’s poetry is most of all, accessible. It is about the mundane, it is about experience, and it brings the mundane experience in touch with the spiritual and the profound. When I was preparing this essay and thinking about the ways in which Sengupta’s writings were democratic, one of my first thoughts was that he focuses upon life’s and nature’s details, he looks to them for enlightenment and meaning. He does not restrict his attention to “higher thoughts” and he seems to have an absolute faith that the real world about him holds the key to gaining the most from living. He captures this beautifully in his poem, “Experience Personified” from The Earthen Flute:

As I walk along an abandoned playground

In the morning, I see new grasses bathed

In the dew of dawn

Putting off my shoes I stand barefooted

and I walk again

Tiny droplets envelop my feet

And permeate the skin of my toes

I don’t call it a feeling

I would rather name it

My experience

Sengupta’s attitude of finding meaning through the ordinary, of gaining profound insights by allowing oneself to be open to all sides of oneself as well as to the myriad aspects of the world around one is not only captured in his poetry, but he expresses it extremely well in a statement in Reflections on Salvation, a statement that I described in the Foreword of the book as “refreshing and even astounding.” He says “Salvation is but enlightenment, achievable only by actions and through your sensory gateways” —a refreshing thought for an atheist, such as myself, but hardly one to be expected from an Indian poet steeped in the spiritual writings of his own land.

I would be delinquent if I neglected to mention Kiriti Sengupta’s generosity, which is both a sign of his personal kindness and also another indication of his democratic attitude. One of his books is A Freshman’s Welcome, a written version of his speech at the formal launch of the first book of poetry by the young poet, Tanmoy Bhattacharjee. Sengupta’s hope, in publishing his remarks, was to “boost the zeal of all struggling poets who wish to become published authors.” Apparently the two poets, the older, more experienced one and the neophyte, met on Facebook, another indication of Sengupta’s eclectism and democratic attitude in his choice of the media he uses to widen his acquaintances and experiences. In fact, he was attracted to reading Bhattacharjee’s poetry partly because the young poet was an academic student of English literature and allied his poetry with a personal “spiritual quest.” In Sengupta’s words, “My limited understanding of spirituality often leads me to listen to others, especially the new poets who wish to get heard. I was eager to know whether Tanmoy’s academic interest and studies have influenced his esthetic and critical consciousness.” This is the question of a person who is open to the experiences of others and who is engaged in seeking salvation through his actions and sensory gateways.

Of course one of the most gratifying indications of Kiriti Sengupta’s generosity and democratic attitude was his review of my own science fiction novel, The Peacemaker, which he generously placed in the Huffington Post. He began his review by saying, “I can hear someone is whispering: ‘What is Sengupta doing here? Does he not have enough assignments to keep him busy?’” And of course the other question that naturally occurs is what is an Indian poet doing reviewing an American science fiction novel? The review was insightful and, being true to the complicated issues of his own spiritual tradition and his naturalistic appreciation of the insights provided by the real world, Sengupta detected an echoing message in my own work. “The Peacemaker is an out-and-out spiritual novel that has no strings of religions or prophecies attached to it,” he wrote. He had gotten the message of my book. I had tried to touch the reader’s sense of spirituality through appreciation of the natural wonders around him or her, with no sense of a higher being or force behind it all. And Kiriti Sengupta listened. Now that is an open, inquisitive, accepting and democratic attitude.

Kiriti Sengupta

Kiriti Sengupta is the author of the best-selling trilogy: My Glass of Wine [novelette based on autobiographic poetry], The Reverse Tree [nonfictional memoir], and Healing Waters Floating Lamps [poetry]. He is a bilingual poet and translator in both Bengali and English. Sengupta’s other works include: The Earthen Flute [poetry], A Freshman’s Welcome [a chapbook on memoir with literary critique], My Dazzling Bards [literary critique], The Reciting Pens [interviews of three published Bengali poets along with translations of a few of their poems], The Unheard I [literary nonfiction], Desirous Water [poems by Sumita Nandy, contributed as the translator], and Poem Continuous – Reincarnated Expressions [poems by Bibhas Roy Chowdhury, contributed as the translator]. His poems have been widely anthologized, both nationally and internationally in Kritya, Taj Mahal Review, Labyrinth, Grey Sparrow Journal,Dukool,Wilderness House Literary Review, among other places. Reviews of his works can be read on The Fox Chase Review and Reading Series, Muse India,Red Fez Magazine,Word Riot, and in The Hindu Literary Review, to name but a few. Sengupta has also co-edited four anthologies: Scaling Heights, Jora Sanko – The Joined Bridge, Epitaphs, and Sankarak.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!