Award nominated Poet Yahia Lababidi shares his thoughts and feelings about the creative process, the role of an artist in society and his recently published collection of poems: Fever Dreams with Val B. Russell

Opening a volume of poetry is very much like opening a door to the poet’s emotional life and internal struggle to understand the human experience.Condensing a million truths into one finite statement called a poem is a blending of the intellect with the spirit that is often contrary the pragmatic approach required in daily life.

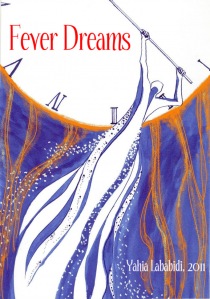

When I walked through poet Yahia Lababidi’s door with his recently released volume I encountered a richly textured, sardonic and often wry account of moments lived in contemplation amid the chaos of an external world that is often contrary to this striving for the answer to the eternal question of what it means to be alive.

VBR: Every poet has their own way of entertaining the muse and putting passion on the page. What is the process for you when you write a poem?

YL: You know, in all honesty, I have no process. Each time I write a poem is a surprise. And, when I’m not writing a poem, I don’t feel very much like a poet. What do I do to try to get there? Reading helps, silence helps, solitude, too. But, all these are no guarantee that a poem will grace me with its presence. So, I try to watch the worlds (inner and outer) as closely as I can, while stock-pile impressions, until the next time that I’m creatively employed.

VBR: You have such an extensive and versatile range of subject matter in Fever Dreams, that at times the atmosphere of the text was delightfully unpredictable. When you were in the throes of putting together this collection was it intentional to maintain an element of surprise for your reader?

YL: Thank you. Yes, an element of surprise is a good idea, for reader and author, alike. For all the poems that have gone into Fever Dreams, there are probably about just as many that I did not include – because I felt like I was repeating myself, or I’d made my case better, elsewhere. I don’t think books can ever quite match life’s richness; but I believe that just as one should read widely, they ought to write widely, to better represent the variety of life’s experiences.

VBR: You make some social and political statements in this book that caress the sensibility in such a way as to be almost subliminal in their delivery. This is a delicate dance for any poet but you do it exceptionally well, without sounding the least bit admonishing or preachy. The poems What is to Give Light, Dog Ideal, Air and Sea Show and Learning to Pray. Do you feel it is an artist’s responsibility to be of their time and to share their observation whether it is politically correct or not?

YL: This is a very important question, and one I’ve been torturing myself with since the Arab Spring began. I’m relieved you say I do not come across as admonishing or preachy; this is my horror. Yes, I agree that the artist lives in their time, and is required to act as a witness. But, I also feel that poorly-digested politics make for bad art… and I also believe that the artist lives outside of their time, belonging just as much to the past as to the future. I’ve recently written an essay on this, which speaks my mind more fully than I am able to, now, on the role of the poet in times of political crisis: http://mantlethought.org/content/poetry-and-journalism-spirit

After writing this piece, I arrived at the understanding that: “At its heart, poetry is apolitical—even if it is sometimes employed in the service of politics—since it cannot take sides… Poetry can act as a sort of alarm system, activated when we’ve strayed, trespassed or tripped into unholy territory… A report on the life of our collective spirit, a reminder of our higher estate, and allegiances to one another and life.”

VBR: The poems In Memoriam and Poy moved me deeply because the imagery was bittersweet and these in particular remained with me afterwards. When you are giving live readings of your work, are there certain poems that are more difficult to articulate because of the intense emotion that inspired them?

YL: Truthfully, I’m still making peace with the writerly life; which is to say the irony of an intensely private person in a public profession. It’s one thing to share one’s diary with the world, so to speak – out of some deep, inner compulsion as an artist. But, it’s another thing altogether having to get up and actually read that “diary” before the world… Which is to say, yes, I do have difficulty with readings, in general. While, I’m always grateful to be asked, I’m still working on the detachment required to share such intimate moments with strangers: of heartache, existential doubt, even mourning. Lighter-hearted poems, or prayer-like odes to life, poems of praise, these afford me more distance and leave me feeling less-exposed, it’s true.

VBR: any people who are new to your work may not be aware that you have a rather extensive and impressive publishing history, having been translated into several languages. In addition to this you are also a seasoned aphorist. When I was preparing for this interview I took a stroll through some of your aphorisms and what struck me was that Yahia is a type of teacher and his readers are in a way pupils. Do you feel this is a calling for you as a poet, to teach or enlighten others in some way?

YL: You are very kind. The only way that I might accept such a generous compliment is to say that I am still aligning myself with these so-called insights (in aphorisms, for example). I say in one aphorism that our wisdom always mocks us, since it knows more than we can. That said, I do see the role of the artist, broadly, as being one of edu-tainment: educating while entertaining. The balance of this serious play is key. Too much to one side, and its pompous; too much to the other and it becomes frivolous.

VBR: You are an Arab writer and your cultural fingerprint is all over your poetry and yet you are a sort of chameleon artistically, shedding that culture and being naked in your humanity to make stark statements about the life we live and our struggle to understand ourselves as well as other human beings who share the world we inhabit. When you write does the poem come along of its own accord or do you begin with an intention and build on it from there whether it is cultural in nature or more expansive and universal in reach?

YL: That’s beautiful: shedding culture and being naked in our humanity. I don’t think I could say much to improve on that. When I’m writing, poetry especially, it’s as though I am semi-conscious. In this dream-like state, I hardly think of myself as an Arab man; at times I scarcely feel human. What I’m concerned with is saying something true, without the least regard for my person or my specific background. And, it’s a paradox to say this, but the more personal I perceive something to be, the more likely it is to connect with strangers, universally. We belong more to one another, than we do to any nation state. As Shakespeare puts it, quite bluntly: “If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh?” It’s really that basic.

VBR: As a poet, I am always enamored of those who can make a transition from intellect to feeling within the same verse because poets often belong to one order of expression or the other. Blending emotion with intellect can be much like oil and water, exclusive of one another and opposed. You manage to weave your emotion through some very heavy intellectual words, specifically in the first poem in Fever Dreams, Words and Fanciful Creators. The latter carrying the banner of emotion through the use of critical wit while describing from a detached intellectual vantage point, the flaw in the worship of progress and ease over depth and meaning. Is it more natural for you to approach your poetry from an intellectual basis or is it emotional territory that requires you to sculpt a little to achieve some equality between the two?

YL: You are a close reader (in between the lines) and it’s a pleasure to think outloud with you through these questions! I see what you mean about intellect and feeling; and how hard it is to mix the two in poetry. My background, and primary love perhaps, is philosophy. Yet, philosophy and poetry can be like the marriage of heaven and hell, I know. Still, they’re both parts of me, and how I perceive the world: the analytical side and the emotional. I will say this, though, more and more, I am less enamored of the mind, its tyranny and seductions. What I’m finding is displacing my fascination with the life of the mind, is a deep respect for the life of the Spirit. In this open space, there are no contradictions and everything is possible.

Words

Words are like days:

coloring books or pickpockets,

signposts or scratching posts,

fakirs over hot coals.

Certain words must be earned

just as emotions are suffered

before they can be uttered

— clean as a kept promise.

Words as witnesses

testifying their truths

squalid or rarefied

inevitable, irrefutable.

But, words must not carry

more than they can

it’s not good for their backs

or their reputations.

For, whether they dance alone

or with an invisible partner,

every word is a cosmos

dissolving the inarticulate.

~Yahia Lababidi~

Fever Dreams, Crisis Chronicles Press 2011

Yahia Lababidi is on twitter

Val B. Russell is the creator and managing editor of Tuck Magazine as well as a Pushcart nominated poet and novelist.

Yahia....the things you have said in this interview have echoed my soul so perfectly and eloquently...thankyou! I am humbled and excited all at once to be a fellow poet. I feel it when you say that "poetry...is concerned with saying something true...that the more personal...the more likely it is to connect wiht strangers, universally." I've always felt, although with a good dose of a sense of unworthiness, that I have to use my 'gift' to say the things that others may not be able to articulate...to give them some kind of a voice...to find a semblance of peace with their own feelings. And I agree that a poem is "more likely to grace me with it's presence", when "I am less enamored of the mind, its tyranny and seductions", that the Spirit is the true source of the truest poetry. It is as you say..."every word is a cosmos dissolving the inarticulate." Thankyou again Yahia.....Kaz.